Seeing regional market advantages, a junior miner hopes to reopen a Spanish potash district

By Steve Fiscor, Editor-in-Chief

In an area less than 50 km from Pamplona, Highfield Resources is planning to open the Muga mine, which will extract potash from sylvinite beds in an 80-km2 deposit. The company believes the deposit starting at depths to surface of less than 200 m is ideal for a relatively low-cost room-and-pillar mine. The rural setting offers plenty of room to construct a mineral processing plant. The product has access to national road networks, rail and various ports along the Atlantic Coast making it relatively easy to ship product to European, East Coast U.S., West Coast African and Brazilian customers. If all goes as planned, the Muga mine could break ground as soon as the third quarter of 2016, reaching commercial production in 2018.

Widely known for the Festival of St. Fermin and the running of the bulls, Pamplona has a strong Basque influence and a rich mining history. The Basque term “muga” means “border” or “boundary.” The Muga project sits alongside one of the minor Camino de Santiago (St. James’ path) routes known as the Aragonese Way (this route joins the French Way that goes through Pamplona at the Navarran town of Puente la Reine) on the border of the Spanish states of Aragon and Navarre.

After collecting a wealth of information about the deposit and optimizing a definitive feasibility study (DFS), Highfield is in the process of securing permits and the necessary financing to begin construction. The four major European banks backing the company’s Spanish development projects recently commissioned an independent report on the potash market. The report, which included a specific focus on the Muga project, confirmed that, based on average potash prices for 2015, Highfield would have

high margins and likely be the lowest cost potash producer on a delivered basis into its target markets (Europe, Brazil and the U.S). The costs included all cash costs required to get 1 ton of muriate of potash (MoP) product to the point of sale in the relevant market.

“We continue to believe we have the most compelling potash project globally, and this is the first of our portfolio of five projects that all appear to exhibit similar characteristics,” said Anthony Hall, managing director, Highfield Resources. In addition to the Muga project, the other four potash projects are Vipasca, Pintano, Izaga and Sierra del Perdón, all of which are located in the Ebro potash producing basin in northern Spain, covering a project area of more than 550 km2.

The Sierra del Perdón project includes two former potash mines that were known as Potasas de Navarra and Potasas de Subiza. Sierra del Perdón produced potash for about $100 per metric ton (mt) at a time when potash was selling for $100/mt. The company needed a significant upgrade in infrastructure to open new sections of the mine, which resulted in the Navarran government deciding it no longer wanted to produce potash and closed the mines in the late 1990s.

Highfield has a promising project with some clear advantages over traditional potash operations. Already, the company has signed its first memorandums of understanding for potash offtake with three large fertilizer companies, active in the Spanish and French markets for 320,000 mt/y of K60 MoP. They expect to receive a positive environmental declaration soon and then construction can begin on the Muga mine.

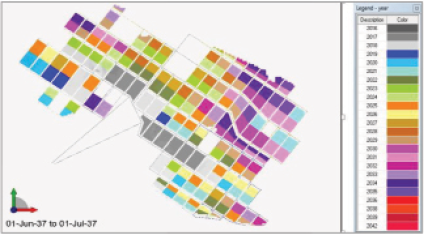

Figure 1—Location of Highfield’s Muga, Vipasca, Pintano, Izaga and Sierra del Perdón Projects in northern Spain.

The Muga Mining Plan

Muga’s life-of-mine plan has two phases. “The first phase, which is Muga 1, will take the mine from the construction phase to half of its commercial production capacity,” said Michael X. Schlumpberger, executive general manager-operations for the Muga potash mine. “During phase 2, underground production would ramp up to full capacity.” While RoM ore tonnages will vary, the mine plan has been designed to ensure the processing plant will ultimately produce 90,000 mt/month of granular K60 MoP product (or 1.08 million mt/y of GMoP), which will require more than 6.3 million mt/y of run-of-mine (RoM) ore.

Highfield completed its DFS in March 2015. As the company turned its attention to construction and ultimately production, it made several realizations during the underground design and equipment selection process that would improve operational efficiencies. This information was used to further optimize the Muga project and company released an optimized DFS in November 2015.

The measured and indicated mineral resource estimate is 224.5 million mt at an average grade of 13.4% K2O based on a minimum 1.5-m bed thickness and grade cutoff of 8% K2O-in-sylvinite. The estimate also includes beds thinner than 1.5 m where the grade exceeds 12%, satisfying the 8% K2O-in-sylvinite at 1.5 m cutoff. Recognizing that the K2O contained in carnallite is unlikely to be recovered in the proposed ore treatment method, it was not included.

The sylvinite mineralization occurs in seven beds, ranging in depth from 100 m to more than 1,500 m. The original mine plan targeted four beds in two areas, an eastern zone and a western zone (See Figure 2). The new mine plan was altered to include an additional sylvinite bed, which extended the mine life to 47 years from 24 years.

Instead of relying solely on road-headers, the company elected to use a combination of continuous miners and road-headers to increase productivity in both production and infrastructure development. By increasing the number of main headings from one to three, they could reduce ramp up risks and increase operational efficiency. The size of the mainline underground conveyor and storage system, and the decline conveyor were

all increased so they could provide a steady feed of 1,500 mt/h to the processing plant.

Importantly this also enables further expansion with the company believing that Muga has the potential to produce around 2 million mt of potash for a period of more than 30 years.

The various mining horizons will be accessed using two straight 5- x 7-m declines approximately 2.5 km and 2.6 km in length. “Spain has a rich heritage of tunneling and infrastructure development,” Schlumpberger said. “When we tendered for the ramp construction, we had 10 choices for contractors.”

The eastern decline reaches the mineralized horizon at 440 m below surface and the western decline approximately 452 m below surface. “We will use the east ramp for conveyance,” Schlumpberger said. “The west ramp will be entry and emergency egress and primary ventilation. As the mine develops, we will sink some short shafts to assist with ventilation.”

At the bottom of the decline, miners will drive two sets of main headings (north and east) using a three-entry system with panel belts for the development sections running perpendicular to the mains. “We decided to use a three-entry system for development,” Schlumpberger said. “It offers more options than a single heading as far as ventilation, regress and production efficiencies.”

Depending on the geology and bed height, the room-and-pillar mining method will use a combination of continuous miners and road-headers to minimize dilution. “The use of road-headers gives us some flexibility with regard to selectively separating the sylvinite from the halite,” Schlumpberger said. “The continuous miners are more productive than road-headers and the increased tonnage offsets the poor selectivity.”

A little less than 20 years ago, Sierra del Perdón was extracting sylvinite using both room-and-pillar and longwall mining methods. The use of the longwall mining method lends credence to the competence and uniformity of the ore body and more importantly the lack of an aquifer, Schlumpberger explained. “The lack of an aquifer is one of our strategic advantages,” he said. “If a potash operation encounters an aquifer above the beds they are usually forced to use shaft access. When a decline pierces an aquifer, water flows down the ramp into the mine. Potash miners do not like water. With shafts, they can freeze their way through the aquifer and isolate the water from the operation.”

Sinking shafts is an expensive proposition that can exceed more than $500 million as is currently being demonstrated by BHP in its Jansen potash project. “Muga’s two declines, including the conveyor system will cost less than $30 million,” Schlumpberger said.

The decline conveyor will transport RoM ore to permanent storage buildings on the surface. “Those will be designed in-country,” Schlumpberger said. “Any place we can use in-country design, we are using it. If we need a specialized contractor with potash experience, then we use foreign contractors.”

Highfield intends to use paste backfilling, however, this will not be implemented until Muga’s Phase 2 begins construction. Backfilling will increase the life-of-mine extraction ratios for each panel from 55.7% to approximately 80%, and also provide long-term geotechnical stability, minimizing the risk of subsidence.

Figure 2—Mine panel configuration by east and west zones across the four principle mining seams.

Recovering GMoP

Highfield has engaged several globally recognized consultants, who are world leaders in the processing of sylvinite ores and have been involved in the design process for many plants, to develop and supervise the completion of a series of detailed metallurgical test work programs.

They discovered that the ore, in general, exhibited a positive metallurgical response, with a clear advantage for the banded ores over the brecciated ores. The consultants also confirmed the metallurgical properties of the Muga ore lends itself to a simple, proven process flow sheet, which has been successfully implemented at many operations globally.

The metallurgical recovery process is based on ore characterization. The geochemical composition of the Muga ore includes magnesium and some insoluble content. Highfield expects the recovery rate to range between 90.6% for the purely banded sylvinite ore to 79% for purely brecciated ore. The weighted average recovery, according to the current DFS, is 88.3% potassium chloride (KCl) or potash.

“The Ebro Basin ore is not Saskatchewan grade ore,” Schlumpberger said. “It has a lower grade, similar to the potash that’s mined by Belaruskali or K+S. It is a dirtier sylvinite ore that does not have as high of a KCl/K2O factor, so we had to engineer the processing plant accordingly.

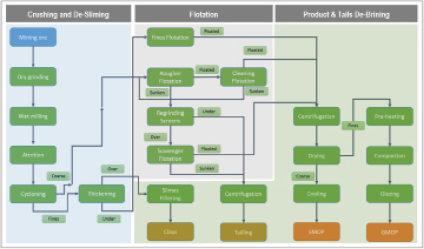

The Muga processing plant will use a two stage crushing process, attrition scrubbing and hydrocyclone de-sliming stage followed by a KCl froth flotation circuit (See Figure 3). “A Canadian engineering firm with potash experience has performed the basic engineering for the layout of the processing plant and we are currently working on the detailed engineering plan,” Schlumpberger said. “It’s a fairly standard configuration with crushing, flotation, regrind circuits, scavenger circuits and cleaner-tailings circuits.

The RoM ore is crushed with dry grinding followed by wet grinding and fed to attrition cells. After the attrition cells, the slurry reports to a series of cyclones to remove the clays. The coarse material passing the cyclones reports to flotation (rougher and cleaning). The float reports to the drying circuit, while the undersize is rescreened and processed through scavenger flotation cells.

The undersize from the cyclones flows to the thickener where the undersize material reports to a fines flotation and drying. The slimes are filtered and report to the tailings stream. “Both the product and tailings are dewatering using centrifugal dryers,” Schlumpberger. “After the centrifuges, the product is dried using fluid bed dryers and then conveyed to a compacting and glazing facility for conversion from standard MoP to GMoP.”

After drying, compacting and glazing, the product reports to GMoP storage where a de-dusting oil will be applied in a set of trammels. The product is then transported to the loadout facility.

“One of the nice things about this operation is that we will recover brine that helps with recovery,” Schlumpberger said. “A potash operation wants saturated brine in its process. We are going to recover brine from the decline, the tailings storage facility (TSF), and the process recovery areas; all of these areas will help us achieve saturated brine. Anytime you introduce fresh water into a potash operation, you lose recovery. We want to have saturated brine, preferably KCl saturated brine, so we lose less recovery off the operations.”

The plant produces two streams of tailings: slimes containing clay, sodium chloride (NaCl) or salt and KCl (8% to 10% by content); and salt tailings containing NaCl, minimal KCl (2% to 3% by content) and water. A backfilling strategy has been designed to place all salt tailings back into the mine. Small quantities of cement will be added to the salt tailings in a paste backfill plant on surface before the tailings are piped underground to fill the old works. Backfilling has two benefits: the tailings are placed underground rather than storing them on the surface and it minimizes subsidence.

Around 20% of the slimes will also be added to the salt tailings and piped underground. The balance of the slimes will be stored on surface. Highfield is considering a crystallization option to process the slimes to produce high-grade potash (K62) and vacuum salt.

Highfield is currently evaluating two options, hydraulic and thickened tailings, for its TSF. The company is also working with several firms as far as geometallurgical testing.

“We are currently working with Barr Engineering and Patterson & Cooke to determine the best options for the TSF and the backfilling process,” Schlumpbegrer said.

“Currently, we have core in South Dakota with Respec. That core will eventually be sent to Saskatchewan for more metallurgical testing. Respec has a lot of expertise with salt and potash and they use hydraulically loaded cells for creep tests, which are continuously monitored in a temperature-controlled environment.”

Figure 3—Process Flow Diagram.

Financial Viability

The capital costs for Phase 1 are estimated to be €267 million including 5% contingency for construction costs and an additional 10% contingency for equipment related costs. This will allow the development of a mine capable of producing 540,000 mt/y of K60 GMoP.

The Phase 1 capital cost estimate includes the construction of two declines into the mining horizon, flotation and compacting capacity, and the RoM processing. In addition, it includes drying capacity for up to 1.1 million mt of GMoP. It also includes all surface and mine infrastructure including product storage, access roads, electricity connection, gas supply, water and communication.

Phase 2 capital costs are estimated at €146 million and correspond with the expansion of the underground mine and sections of the aboveground facilities to increase mining production to deliver enough ore to the process facilities to produce an average of 1.08 million mt of K60 GMoP. The estimates also include the requisite expansions of capacity at the process plant including new buildings, flotation circuit and compaction capacity.

Relative to the original DFS, the primary change in the operating expense has been an increase in the mining cost from €35/mt to €55/mt of GMoP. This is primarily due to an increase in the movement of waste material and dilution due to the use of continuous miners.

Highfield’s optimized DFS has produced robust financial metrics. Similar to any commodity, potash prices are market dependent and the projected returns for the Muga project are most sensitive to changes in potash prices. Potash sold by the larger producers to the larger consumers in Asia is currently trading in the low $200/mt range. U.S. customers are paying somewhere in the $200/mt-$250/mt range, while K+S demonstrated last quarter that European customers continue to pay between $250-$300/mt, the highest price of any global market. Using a price of $250/mt along with other considerations, such as exchange rates, Highfield believes the Muga project will deliver significant value.

A strong U.S. dollar has a direct influence on the market. Taking Brazil as an example, the real has been devalued against the U.S. dollar, Schlumpberger explained. Brazilian farmers are paying more for potash today in local currency than they were when it was more than $375/mt at the start of last year.

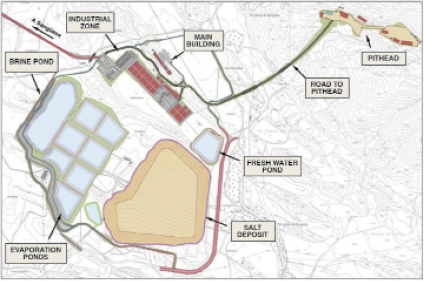

Figure 4—Site layout and infrastructure for the Muga mine and processing plant.

Infrastructure and Logistics

With an eye toward sustainability, Highfield has deliberately tried to minimize the surface footprint of the infrastructure required for the Muga project. Where possible, the design has been adjusted to allow the use of natural features, such as valleys and rises, to ensure that the visual impact of the project on the surrounding area is minimized, Schlumpberger explained.

The Muga mine will pull power from the grid and Highfield has secured 60 MVA of capacity. The DFS estimates that less than 30 MVA will be required at peak periods during full production, giving them additional capacity for further expansion.

“The beauty of our project is that it is truly a mining project and the transportation infrastructure already exists,” Schlumpberger said. “We will truck the GMoP 140 km to the Port of Pasajes at San Sebastián. We also have an option to ship ore through the Port of Bilbao farther to the west and another option in France to the east.” Highfield has signed non-binding agreements with the Port of Pasajes and the Port of Bilbao, which confirm the ability to ship significant quantities of product through these ports.

“While we do not have the highest grade ore, we do not have to pay royalties and we do not have to build all of the infrastructure,” Schlumpberger said. “We are targeting high margin customers in Europe, U.S., western Africa and Brazil. All of those areas command higher prices and we have the logistical advantage of being located in western Europe.”

Spain currently operates under a caretaker government. “While there is the possibility that permits could be rejected, our feeling is more about when the mine will start construction rather than if it will start construction,” Schlumpberger said. “The current Spanish unemployment is 23%. We are going to add more than 800 direct jobs and multiples of indirect jobs. The current caretaker government has been issuing permits. The legislated period for permits is four months plus two months. We are now over the six-month period and the reality is we could receive the permits any day now.”

Highfield has entered into a collaborative agreement with Acciona Infraestructuras, part of the Acciona Group, to construct the Muga potash mine. Acciona is a Spanish-headquartered company and has many years of experience in construction in Spain. Under the collaboration agreement, Acciona is working with Highfield over a three-month period to prepare a submission to construct the mine and installations under a guaranteed maximum price contract where it is responsible for program, cost and quality risk.