By Simon Walker, European Editor

While the Nordic countries have not been immune from the current slowdown in exploration activity, there is still plenty going on as companies continue with project developments. E&MJ looks at some of the challenges—and the continuing successes.

Worldwide, exploration spending has been one of the most prominent casualties of the current wave of economic uncertainty that has been bathing the mining sector. The Nordic countries—Norway, Sweden and Finland, together with Greenland—have been no exception to this trend, with many of the junior companies that were featured in last year’s review in E&MJ (See October 2012, pp. 38-50) now reporting reduced drilling budgets and, more alarmingly, a much tighter funding environment.

Again on a global scale, the most recent edition of information provider IntierraRMG’s State of the Market snapshot on exploration, it emphasizes that companies have indeed been struggling to find the money they need for their projects. “Falling metals prices, nervous bankers and risk-averse investors contributed to a further slump in funds raised [from the previous quarter], with only $431 million* received for exploration programs in the three months to end-June,” the company said. And, with that amount covering the whole world, it is easy to see why spending in the Nordic region has been hit especially hard.

No matter that the Nordic countries bask in a wholesome reputation for stability, probity and administrative transparency. No matter that Sweden and Finland in particular have a world-class (and still relatively untapped) geological endowment. No matter that these are renowned as being good places to do business. The money is not there, and the junior exploration companies are cutting their cloth to suit.

Another worrying aspect that has emerged since last year’s review relates specifically to the iron-ore sector. With the world’s steel industry nervous over demand trends, and big producers such as Australia and Brazil still in the middle of vast production capacity expansion projects, some of the world’s smaller suppliers have found it tough to keep going for over the past 12 months.

Recent data from the World Steel Association suggest that crude steel production for the first six months of 2013 was 789.8 million metric tons (mt), a 2% increase year-on-year with—perhaps unsurprisingly—Asian producers leading the way. However, that can have been of little comfort to the smaller Nordic producers, since Asia is not really their prime marketplace. By contrast, not only was crude output from steelmakers in the European Union 5.1% lower in the first-half of 2013 compared to 2012, but also a whopping 9.8% down on the equivalent period in 2011.

Little wonder, then, that some of the emerging iron-ore suppliers have been in trouble, given the double-whammy of rising capex costs for their new operations and lower demand in their backyard markets.

The other area where Norway and Iceland in particular offer major advantages over competitor countries is in energy supply. Norway’s hydro-electricity resources have long been the foundation for not only its aluminum-smelting sector, but other metallurgical plants as well. Iceland offers similar, if smaller, opportunities, while Sweden and Finland are home to major base-metals smelting operations that draw their feedstocks from both domestic and import sources. Even fertilizer production is big business, again drawing on local resources such as phosphate-bearing rock and hydrocarbons as its raw materials.

In an uncertain economic climate, it could be easy to be somewhat gloomy about the state of exploration, mining and metallurgy in the Nordic region. Instead, this edition of E&MJ’s annual Nordic review focuses on the strengths of the industry in this part of the world, which is continuing to attract international attention as a major mining center.

The Geological Endowment

In simple terms, most of Finland and much of northern Sweden consists of Precambrian basement—the Baltic Shield—while on the other side of the north Atlantic, Greenland is predominantly underlain by a section of the Laurentian Shield that extends across northern Canada. Between the two, on the eastern side of Greenland and through Norway, rocks of the Caledonian fold belt run up against the older basement blocks, with oceanic spreading having separated them into two of what was originally a continuous structure.

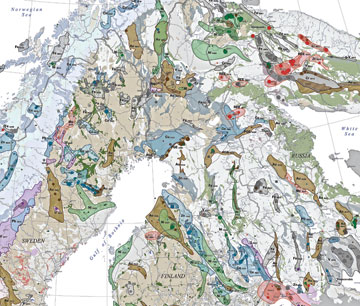

Part of the new Fennoscandian Metallogenic Map, published earlier this year by the Geological Surveys of Finland, Norway, Russia and Sweden. Reproduced by permission from the GTK. For more information: http://en.gtk.fi/informationservices/databases/fodd/.

Historical mining for iron ore, copper, zinc, lead and silver within the more accessible parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland proved that the potential of the Baltic Shield rocks hosting economic deposits was no less than that of shield areas in other parts of the world. Indeed, with the possible exception of far southern Sweden—and, of course, of Denmark, which has never hosted a mining industry of note—virtually the whole of the Nordic region offers attractive exploration potential. Remember as well that the Baltic Shield does not stop at the Finnish border, and that neighboring regions of Russia not only support long-standing mining industries, but also remain substantially under-explored using current technology.

Over the past quarter-century, national governments have progressively liberalized exploration and mining, moving away from state control to relying on private-sector investment. A few vestiges of state ownership remain, notably in the form of the Swedish iron-ore company LKAB, although even this has been restructured as a public-limited company so as to give it better access to funding for its long-term development programs.

The moves have galvanized the region’s industry, with major investment in both exploration and new mine developments. In addition, companies have used the recent commodity price boom to revisit old mines that offer reopening opportunities—some of which have already proved viable.

The national geological surveys in each of the Nordic countries are well organized and hold substantial amounts of data, both regionally and location-specific. In addition, there is a high level of cooperation between them, as shown earlier this year by the publication of a new edition of the definitive map and accompanying datasets for all the metal mines and deposits in Fennoscandia (Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Karelia and Kola Peninsula regions of Russia).

Produced for use as a tool in selecting strategic areas for mineral exploration as well as for research in economic geology, the new map represents a major update to the first edition that was published in 2008. It shows the position of nearly 1,700 deposits in the region, 40% more than were shown on the 2008 version, and according to one of the organizations involved in its compilation, the Geological Survey of Finland (GTK), 61% of all the deposits on the map have never been exploited—excluding around 500 mostly very small historic mines. The GTK goes on to point out that a number of these deposits might well be economic in the future once additional reserves have been located by further exploration. In all, the new map shows that today there are 61 active metal mines, 59 large unexploited deposits and 48 potentially large unexploited deposits in the region.

Looked at from a national perspective, 883 of the deposits shown lie in Sweden, 351 in Finland, 246 in Russia and 210 in Norway, a split that illustrates beyond question the wide distribution of economic resources across northern Europe.

Highs and Lows with Iron Ore

One of the main regional features of the past few years has been the enthusiasm with which a number of small companies have been re-evaluating old iron-ore mines. None of these deposits can compete directly with the high-grade producers in countries such as Brazil and Australia, so in each case, pellet or sinter feed has been the target market. Project developers have struck offtake deals with steelworks in Europe and further afield, as well as selling to commodity traders.

An underground locomotive workshop on the new haulage level at Kiruna, which will reach full capacity in 2017. (Photo courtesy of LKAB)

An underground locomotive workshop on the new haulage level at Kiruna, which will reach full capacity in 2017. (Photo courtesy of LKAB)

Not that Sweden’s big producer, LKAB, has been idle either. In May, the company celebrated the official opening of the first of five stages in the development of the new haulage level at Kiruna. The culmination of nearly five years of work, the 1,365-m deep haulage level has involved the largest investment in LKAB’s history, with the aim of guaranteeing the operation’s future for the next 20 years at least. When in full production, it will handle 35 million mt/y of ore.

The section of the level opened in May consists of three groups of shafts, each comprising four ore passes, two train sets, a crusher and a skip hoist, as well as all the infrastructure and automation needed to keep the level running. The remaining four stages will involve the addition of more production areas, groups of shafts, trains, crushers and skip hoists, with the entire project scheduled for completion in 2017.

“This is an unusual project; partly due to its size, but also because it extends over such a long period. From the pre-project phase to completion, we’re talking 12 years,” said Hans Engberg, the project manager for the new main level. “This has placed special demands on our organization and planning.

“We have managed to assemble a fantastic team and, thanks to good cooperation, we have been able to solve many complicated and difficult problems,” Engberg added.

LKAB itself produced 26.2 million mt of products during 2012, comprising a record 23.8 million mt of pellets and 2.4 million mt of fines. The company has begun its LKAB 37 expansion program that is targeting an output of 37 million mt/y of finished iron-ore products by 2015, while on surface, it will have a major relocation task on its hands over the next 20 years as large sections of both Kiruna and Gällivare will need to be moved away from subsidence zones.

With the northern European steel industry badly affected by the downturn in demand in the second half of last year, LKAB was able to redirect a proportion of its sales tonnage to other customers in the Middle East and Asia.

Having had its Gruvberget surface mine at Svappavaara closed by court order in mid-2012, LKAB was able to resume production there at the end of the year under a temporary environmental permit. It is also pumping out the Leveäniemi open pit, with a target to begin production next year, as well as applying for permitting for the Mertainen open pit where production may begin in 2015.

Smaller Producers Hit Hard

Despite its increased output, LKAB reported revenues 14% down year-on-year, while net profits were nearly 20% lower as the iron-ore market softened. The company’s size gave it the flexibility needed to withstand this level of downturn; others were not so lucky.

Having brought its Kaunisvaara mine into production (“from bog to mine,” as the company put it) in February, Northland Resources was forced into corporate reconstruction after it became clear that it needed additional funding. Not only were its capex costs higher than expected, but its initial operating costs were higher as well. An abortive share-and-bond issue in January exacerbated the crisis for the company, which had already produced 65,000 mt of 69%-Fe concentrate—55,000 mt of which was shipped to Tata Steel’s plant in Holland in February.

Northland and its creditors have since agreed on new long-term financing, with the reconstruction period ending in August. A four-party consortium that includes both LKAB and the equipment supplier, Metso, has invested $100 million in a new $335-million bond issue aimed at providing the company with adequate liquidity.

LKAB’s $25-million participation came through its holding in the venture capital provider, Norrskenet AB. “Together with the other companies in the consortium, we wish to re-establish confidence in Northland,” said LKAB president and CEO Lars-Eric Aaro. “This benefits not only the company, but also our region and the entire Swedish mining industry.

“LKAB has a full focus on starting our new mines in the Svappavaara field and realizing our growth plans. This is a financial investment, which is why Norrskenet is participating. Norrskenet’s mission is to contribute, via venture capital, in the creation of a broader economic base in our region,” he added.

Writing in Northland’s interim report in July, acting CEO Peter Pernlöf noted that the company now estimates that it has sufficient funds to complete both process lines at Kaunisvaara, with full capacity at 4 million mt/y of concentrates there before the end of 2014.

However, Northland’s liquidity woes have had a knock-on effect elsewhere in the industry. Having reopened SSAB’s former Dannemora mine last year, with the aim of building an operation capable of delivering 1.5 million mt/y of iron-ore products, Dannemora Mineral subsequently had to raise further capital through both equity and bond issues, and in August sought bond-holders’ approval for a reduction in its minimum liquidity covenant. The company has also been working hard to improve recoveries from its sorting plant. It shipped 233,000 mt of products from Dannemora last year, with the long-term aim of producing 5 million mt/y from this and other deposits in the Bergslagen district of central Sweden and elsewhere in the country. “Next on the agenda is [the] Riddarhyttan [mine],” according to the company’s 2012 annual report.

Nordic Iron Ore CEO Christer Lindqvist put the situation into perspective in his first-quarter report comments. “We have been affected negatively by major problems that have impacted other actors in our industry, which has given the capital market a negative perception of Swedish iron ore projects,” he said. “This means that similar to other companies, which develop iron-ore projects, we will be forced to invest significant resources on capital procurement issues—resources that should instead be used to manage projects further.”

Nordic Iron Ore is currently working on a reopening program for the old Blötberg mine at Ludvika, with a target date of late next year as a stepping stone to a company-wide output of 4.4 million mt/y by 2018. It signed a letter of intent covering 600,000 mt/y of iron ore products with Coal and Ore Trading earlier this year, based on mineral resources that have trebled to some 170 million mt.

Remoteness Proves Challenging

Northern Iron’s Sydvaranger operations in northern Norway, close to the country’s border with Russia, must be among the most remote anywhere in Europe. The company shipped nearly 2 million mt of concentrate last year, up on 2011’s achievement but still short of its earlier targets. Of this, around 1.5 million mt went to European steelworks, with the remainder taking the long haul to China.

A drill crew at the Isua iron-ore project in western Greenland. (Photo courtesy of London Mining)

A drill crew at the Isua iron-ore project in western Greenland. (Photo courtesy of London Mining)

Northern Iron has been carrying out trials on using its concentrate as sinter feed, which it hopes will give it access in the future to the large European market for sinter fines. Not only would this help expand its market potential, but could result in higher revenues since freight costs would be lower. It is also working on a five-year growth strategy for Sydvaranger, leading to a doubling in capacity to 5.6 million mt/y of products. Initial estimates show capex requirements of $280 million to $360 million.

Although it has received some local approvals for its expansion plans, the company has now put these on hold while it “monitors the iron ore market and production performance, and the corresponding impact these have on its liquidity position.”

Meanwhile in Greenland, London Mining began the application process for a mining license for its Isua iron-ore project last September, with the company anticipating that it will receive permitting later this year. Discovered in the 1960s and subsequently evaluated by Marcona and Rio Tinto, Isua has more than 1,000 million mt in resources, with London Mining planning an operation to produce 15 million mt/y of concentrates for pellet feed. It has already completed a bankable feasibility study on the project, which includes an open-pit mine, concentrator, slurry pipeline, loadout port and infrastructure (and $2.35 billion in capex).

Like Isua, the Melville Bugt iron-ore prospect currently being evaluated by Red Rock Resources and North Atlantic Mining Associates is a banded iron formation (BIF)-type deposit. Located in the far northwest of Greenland, with host geology similar to that found at Mary River on Baffin Island and elsewhere in Nunavut, the prospect has both magnetite and haematite potential, the company stated.

If anything, development challenges are even more severe here than in far northern Norway, although as Red Rock pointed out, other companies with Arctic Circle projects are already addressing these. Even the winter sea ice is something that can be accommodated, as both Norilsk in Russia and Red Dog in Alaska have shown. And as for Isua, sea ice is not a problem; the sea on that part of the Greenland coast does not freeze in winter.

Metallurgical Center of Excellence

Even in the Middle Ages, Swedish iron-makers enjoyed an enviable reputation for quality and purity, such that their products were in demand across Europe. In Norway, the turn of the 20th century brought the first use of hydro-electricity—to produce nitrogen for fertilizers. Aluminum came later. Fast-forward to 1949, and the industrial introduction of Outokumpu’s flash smelting technology (now marketed by Outotec) for copper at the Harjavalta smelter in Finland.

Electronic scrap for processing at the Rönnskär copper smelter. (Photo courtesy of Boliden)

Electronic scrap for processing at the Rönnskär copper smelter. (Photo courtesy of Boliden)

Last year, Boliden commissioned the SEK1.3-billion electronics recycling plant at its Rönnskär copper smelter, expanding capacity there to 120,000 mt/y and promoting the company to world market leader in this field. As Boliden pointed out at the time, 1 mt of electronic scrap yields 100 g of gold, while ore concentrates only yield 8 g, with two-thirds of the plant’s annual gold output now being derived from scrap.

Across the Gulf of Bothnia, Outokumpu completed a €410-million expansion at its Tornio ferrochrome smelter ahead of schedule and below budget at the year-end. Now the most highly integrated stainless-steel mill in the world, Tornio encompasses the ferrochrome works, as well as the Kemi chromite mine, a melt shop and rolling mills. Capacity is being ramped up, with the nameplate 530,000 mt/y scheduled for 2015.

Talvivaara Mining’s use of bioleaching at its Sotkamo nickel mine was another industry first, while in Norway, Hydro claims that its recently developed HAL4e aluminum reduction cells offer lower energy use and environmental impact as well as better productivity. “[The technology] is now ready for use the next time we build an aluminum plant,” the company said.

Turning to steelmaking, SSAB is a world leader in the production of high-strength steel at its plants in Luleå and Oxelösund. The company’s short-term goal is to increase the proportion of these products to a half of its total output by 2015. And, as the Swedish Steel Producers Association, Jernkontoret, pointed out, SSAB is not alone in being a world leader in its specific area of steel-making expertise. Other sector companies include Sandvik (No.1 in producing seamless stainless-steel tubes), Erasteel Kloster (No.1 in high-speed steels) and Ovako (No.1 in steels for bearings). What they all have in common is a focus on niche products, and a strong reliance on export markets.

Mergers and Acquisitions

In a year when international players in the mining sector have largely been husbanding their financial resources, there has been a marked downturn in merger and acquisition activity worldwide. The Nordic region has been no exception to this, with only one significant change of ownership—the takeover of Inmet Mining by its Canadian rival, First Quantum Minerals.

The principal effect of this in terms of the Nordic mining scene has been to transfer ownership of the Pyhäsalmi copper-zinc mine to First Quantum, which brought its own Kevitsa polymetallic operation in the north of Finland on stream in the middle of last year. The two could not be more different: Pyhäsalmi is deep with limited reserves remaining, whereas Kevitsa is an open pit that has reserves for 30 years’ of production, and a plan in place to increase throughput from 5.5 to 10 million mt/y of ore.

In the metallurgical sector, in March, the partners in the Tenke operation in the DRC bought the Kokkola cobalt chemicals refinery in southwestern Finland from the OM Group for an initial $325 million. Lundin Mining and Freeport McMoRan Copper & Gold provided the funding for the purchase, effectively carrying Gécamines’ share in the short term. The deal may cost them up to $100 million more, depending on the plant’s future performance. According to Lundin, the acquisition will provide direct end-market access for cobalt hydroxide produced at Tenke Fungurume.

In operation since 1968, the Kokkola plant is the world’s largest supplier of cobalt chemicals and powders for use in rechargeable batteries, chemicals, ceramics and powder metallurgy for the hard-metal and diamond-tooling industries.

Wanted: A Return of Confidence

In many respects, the current environment of reticence over mining and exploration within the international investment community flies in the face of economic reality. No question that the industry has hit a flat spot in the cycle, but overall, the situation could indeed be a lot worse. If only the funding providers could see it that way.

An LD converter at the Oxelösund steelworks. (Photo courtesy of SSAB)

An LD converter at the Oxelösund steelworks. (Photo courtesy of SSAB)

As it is, it seems that only the largest, most secure companies are able to source financing for project development, and with a few exceptions, these are not the main players in the Nordic region. Plenty of the juniors who do have attractive prospects there are having to wait and see how funding markets develop, and when investment dollars will once again become more readily available. Exploration budgets have been trimmed—in common with most other parts of the world—which is clearly bad news for companies who have partially completed projects, not to mention the region’s service companies who look after their geophysics, drilling and assaying for them.

On the plus side, the geological endowment is not going to go away. Huge advances have been made over the past 50 years in gaining a better understanding of the Nordic countries’ resources, and their geo-information systems reflect this. Political will—so often ambivalent elsewhere towards mining—is also strongly supportive, albeit within a well-defined set of guidelines over environmental and social requirements. Hopefully it will not be too long before investor confidence returns as well.

Thorium: Evaluating an Alternative Energy Resource

Since the development of nuclear power for electricity generation, the focus has been on the use of uranium as the main reactor fuel. There was, of course, a strong military background to this choice in the first place, while the ready availability of decommissioned weapons-grade uranium has been a major supply-side handicap for the mining industry over the past 25 years.

Thor Energy began its five-year irradiation project at the Halden nuclear reactor in April. (Photo courtesy of Torbjørn Tandberg)

Thor Energy began its five-year irradiation project at the Halden nuclear reactor in April. (Photo courtesy of Torbjørn Tandberg)

However, uranium has its drawbacks, and there has recently been increasing interest worldwide—in China and India in particular—in revisiting thorium as an alternative fuel for nuclear reactors. In global terms, thorium is about four times more abundant than uranium, and although its principal natural isotope Th232 is slightly radioactive, it is only classed as being “fertile” rather than “fissile.” Because of this, it has to be kick-started before it can be used as fuel, although once the reaction is under way, it can be used to mop up unwanted uranium-fission byproducts such as plutonium. It also has the safety benefit of being much less susceptible to meltdown if a reactor suffers a major failure or accident, as well as offering little potential for terrorists to make use of it for their own political ends.

Earlier this year, the Norwegian company, Thor Energy, began a five-year thorium irradiation project at the nuclear reactor at Halden in the southeast of the country. Thor Energy has already completed a two-year feasibility study that showed thorium to have several advantages over uranium-based fuel, including better waste characteristics, improved proliferation resistance, and abundant raw-material supply. Today, much of the world’s thorium is derived from monazite recovered during rare-earths and heavy mineral sand production. As such, resources are well-known, and are essentially unused.

Thor Energy is majority-held by Thor Corp., which also has interests in thorium resources (through Fen Minerals’ rights to the Fen thorium-rare earths deposit in southern Norway) and rare-earth separation technology, the focus for Norwegian Separation Technology. South Africa’s Steenkampskraal Thorium and Norway’s Statoil Ventures hold minority stakes in the project.

The World Nuclear Association said, “the thorium fuel cycle offers enormous energy security benefits in the long-term—due to its potential for being a self-sustaining fuel without the need for fast neutron reactors.” Thor Energy is now building on research that was carried out years ago in countries such as the U.S., the U.K., Canada and Germany in an effort to move the technology a small step closer to commercialization.