Problem solvers overcome adversity with advances in equipment and technology

By Steve Fiscor, Editor-in-Chief

The accomplishments the mining industry has made over the course of the last 150 years are remarkable. Even though much of the change has been an evolutionary scale-up rather revolutionary, there are those Ah-Ha! moments that led to incredible successes where others had failed.

Throughout this period, Engineering & Mining Journal (E&MJ) has served as a forum for professionals in the mining and mineral processing industries to share information. When the title was launched as the American Journal of Mining in 1866, miners were fanning out across the country in search of minerals. A new frontier was being settled and a group of editors in New York City was trying to make sense of it all.

Miners have consistently turned to technology to unlock that competitive advantage. Pumps allowed miners to dewater the pits, while dynamite replaced black powder with more force to break rock. Compressed air, diesel engines and electricity provided the energy to make huge gains in efficiency. It also allowed miners to pursue deeper and larger ore bodies. Locomotives put horses out to pasture; rubber-tired equipment replaced rail haulage; and today in-pit crushing and conveying systems compete with truck haulage.

The development path for mining is somewhat circular. With all the miners panning for gold, a few had the mental wherewithal to search further upstream for the outcrop. They followed the vein underground. Oftentimes an open-pit mine, using massive economies of scale, would eventually swallow a group of relatively shallow underground workings until it reached its economic limit and then the miners would follow the ore underground again.

Computing technology and connectivity have added a new twist to this amazing world. Assessing reams of data, professionals today make better decisions, more quickly. The technology also warns of impending danger or catastrophic failure. Just as they have for more than 150 years, mining engineers, geologists and metallurgists have applied the latest tools available to their trade.

As mechanization evolves underground, mines consider different caving techniques.

Advancements in Underground Mining

When E&MJ was launched, development on the Comstock Lode was well under way near Virginia City, Nevada. The geology was often described as bread pudding, where the massive native silver nuggets were the raisins in the pudding-like host rock. A system was needed to support the stopes as they extended. Working with the Ophir mine, Philipp Deidesheimer invented the square-set system of timbering. The support system, constructed from readily available wood, exhibited extraordinary strength and could be erected in many different combinations to support a large opening. Square-set timbering changed the course of underground mining.

As the Comstock mines descended deeper, their problems with water grew. Oftentimes miners would encounter massive inflows of hot water. The drainage adits and Cornish pumps could not keep pace with the situation. Adolfo H. Sutro proposed a 4-mile-long tunnel beneath the mines. With headings extended laterally to the Comstock mines, the tunnel could improve mining conditions by draining the water and improving the ventilation. In 1866, Congress passed the Sutro Tunnel Act and 12 years later, it was completed. The portal still exists today as a monument.

Simon Ingersoll, an inventor from Connecticut, built a mechanical rock drill that became very popular. An associate had a contract for excavating rock for the tunnels below Manhattan. They reasoned that a mechanical drill could do the job faster and make both of them some money. Ingersoll received his basic rock drill patent on March 7, 1871. Other drills had been designed for mining, which were mounted on carriages, but Ingersoll mounted his drill on a stand equipped with counterweights. He sold his drill patents and returned to Connecticut to operate a machine shop. In May 1905, the Ingersoll-Sergeant Drill Co. and the Rand Drill Co. merged to form Ingersoll Rand.

Drilling continued to advance and not just for production. Exploration drilling underground allowed miners to determine what might lie ahead and find lost veins. Core drilling is credited with the revival of the Leadville mining district. Johnny Campion (aka Leadville Johnny) used core drilling to develop and extend the life of mines. Owning and operating a number of mines, he mastered the geology of the Leadville district. In 1893, a swing in silver prices forced many Leadville mines to close. Campion and his men timbered through unstable ground and discovered high-grade gold-copper ore and what would become the Leadville Gold Belt. E&MJ also published many other reports detailing how his production foreman found lost veins with core drilling in many different directions.

At about the same time (1890) in Colorado, Lucien L. Nunn built the first power plant to transmit alternating current electricity to the Gold King mine near Silverton, Colorado. Losing money due to the cost of fuel for its generators to power the stamp mills, Nunn proposed transmitting high voltages across land and then stepping it down with transformers.

E&MJ reports on autonomous underground mining in its September 2007 edition.

The system consisted of two 100-hp Westinghouse single-phase alternators (the largest the company made at the time). One was set up in a generator house—it produced 3,000 volts of single-phase AC power at 133 Hertz. It was driven by a 6-ft Pelton wheel under a 320-ft head of water carried in a 2-ft diameter steel pipe. The electricity was transmitted 2.6 miles up the mountain to the mine via two bare copper wires mounted on poles. At the mine, the second alternator was installed in the role of a synchronous AC motor to drive the stamping mill. A smaller single-phase induction motor (developed by Nikola Tesla) was installed as a starter motor to adjust the speed of the larger alternator to match the synchronous speed of the generator.

Surrounded by skeptics, Nunn threw the switch at the Ames power plant in 1891 and they say a blue arc filled the sky as power surged to the Gold King mine. Mining costs for Gold King dropped dramatically and soon low-grade orebodies, previously too costly to mine, now became a little more profitable. Today, the Ames power plant is still running and the Gold King mine is making headlines for other reasons.

Electrification spread throughout the mining districts. By 1913, the use of electricity at the Butte mines in 1913 led to installation of a centralized compressed-air hoisting system, underground locomotives and pumps, and better lighting and ventilation. The new technology supported safer, deeper operations and reduced production costs.

Over time, caving systems grew larger and more complex.

Mechanization Underground

The Climax Molybdenum mine, under the leadership of Robert Henderson, became a world-class model of innovation and underground production efficiency. An MIT mining engineer, he landed a job with Climax Molybdenum Co., near Leadville, Colorado, and eventually introduced the “slusher drift” mining method. Production at Climax increased dramatically. Underground mines throughout the world sought to replicate this technique. Henderson eventually became the general manager of Western Operations for AMAX. Freeport’s moly mine near Empire, Colorado, the Henderson mine, is named in his honor.

As trucks and loaders grow in size, E&MJ documented the growing use of rubber-tired vehicles underground. Many of these primitive discontinuous processes relied on room-and-pillar mining, which has a low recovery rate. Miners began to turn their attention to different caving and stoping techniques that produced more rock using less timber and manpower. The loaders and trucks started to improve the development time for these caving operations. Then, along came the LHD, the load-haul-dump.

International’s 4×4 Pay Hauler transported 50 tons in the 1960s.

Pass matching 200-ton haul trucks with shovels begins in the 1970s.

Making the shift from mucking machines to LHDs was another pivotal moment for the underground mining segment. It was a trial demonstration in a cut-and-fill stope at the Frood mine in 1966 that sparked the trackless mining revolution at the International Nickel Co. (Inco). The company reported that “the powerful low-slung LHD, its 145-hp engine roaring and its heavily lugged tires hugging the stope floor, showed astonishing versatility. Scooping up a 6.5-ton bite of muck in its bucket, it wheeled smartly across to an ore chute, cleanly dumped its load and was back at the muck pile in a matter of seconds for a reload.” Although 27 ft long and just under 8 ft wide, it could make a 90° turn within a radius of less than 21 ft. These units teamed up with mobile triple-boom jumbos for horizontal drifting, while automatic double-boom jumbos drilled upholes. Raise borers, giraffe-like roof-bolting rigs, and 20-ton telescopic trucks enabled underground miners to charge into a new era of mechanized mobile mining, which improved safety and converted more uneconomical to commercial grade.

In the 1980s, mines begin to experiment with LHDs controlled by teleremote systems, removing the operator from the mucking process at the drawpoint. The technology matures to the point where one operator is controlling two or three LHDs from a central controls station on the surface. The mines then begin to consider autonomous operations in some setting or for part of the cycle.

These advancements not only improve safety, they allow mining company to apply block caving principles to larger, low-grade deposits. This practice, which some say was perfected at the Henderson mine in Colorado or the Magma mine in Arizona, will now be applied at Chuquicamata in Chile, Oyu Tolgoi in Mongolia and Grasberg in Indonesia. These large, open-pit mines are now completing the circle and pursuing the ore as underground mining operations.

Advancements in Open-pit Mining

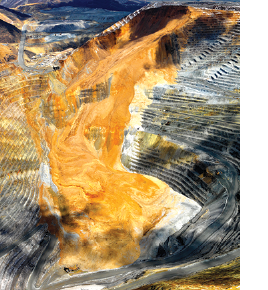

The Bingham Canyon mine in Utah served as a classic case of the evolution of open-pit mining. In 1903, Daniel C. Jackling formed the Utah Copper Co. to mine and process porphyry copper ore found in a mountain in Bingham Canyon, near Salt Lake City. Most of the experts at the time did not believe the operation would be profitable because of the low grade (2%). Jackling proved them wrong. He developed a huge open-pit mine where steam shovels loaded railcars, which transported the disseminated ore to a large mill outside the canyon in Copperton. The era of large open-pit mines begins.

Eventually, Daniel Guggenheim would purchase an interest in Utah Copper Co. and provide much needed capital for further expansion. With mines in the U.S., Mexico and Chile, and smelters and refineries, Guggenheim merged all of the operations into one great company, the Kennecott Copper Corp., which was named for a glacier in Alaska near where his first mining venture began operations. Kennecott would grow to the point where it was the largest copper producer in the U.S. and it owned 15% of the world’s known copper reserves, which also included the Chuquicamata mine in Chile.

Technology allowed the pit to be evacuated before this slide at Bingham Canyon.

For the next 100 years, the Bingham Canyon mine would expand to a depth of 0.75 miles and a width at the top of more than 2.75 miles. The shovels that were originally loading trains directly in the pit would grow size. Eventually haul trucks replaced the trains and they, too, would grow in size. During this period, Bingham Canyon would produce more than 19 million tons of copper.

Today, the mine produces about 100,000 t/y of copper, along with molybdenum, gold and silver. By 2013, the mine was using 12 shovels (10 electric and two hydraulic) to fill an average of 2,100 haul truck loads each day. A fleet of 110 haul trucks, composed of both 240- and 320-ton units, transported ore and waste. The size of the haul trucks gradually increased over time. In the 1980s, the mine operated 190-ton capacity haul trucks before moving to 240-ton haul trucks in the 1990s. During the past decade, 320-ton haul trucks were introduced.

While the history and the size and scope of the operation are significant, what the mine accomplished recently would have impressed Jackling and his contemporaries. During August 2013, Bingham Canyon experienced a slide along a fault-line in its northeastern wall. Using geotechnical monitoring equipment including radar and ground probes, engineers not only predicted the slide, but safely evacuated all personnel from the pit well before the main slide occurred. The elevation at hte top of Bingham Canyon is 8,040 feet above sea level. The 165-million-ton slide stretched from 7,364 ft to the pit bottom at 4,390 ft.

While many thought the operation was doomed, the Kennecott Utah Copper engineers rolled up their sleeves and went to work. In April 2014, E&MJ reported how expedited equipment delivery and assembly was conducted to support and meet a self-imposed November 2013 deadline for finishing certain remediation projects that would allow mining to restart in some parts of the pit affected by the slide. As examples of the hectic pace, a rope shovel was bought, shipped, assembled and commissioned 90 days from purchase order initiation; and haul trucks were being assembled onsite at a rate of four per month.

Remediation-project milestones began to appear and rapidly disappear as work on the slide gained momentum; a haul road into the pit was restored in late October; and remediation of the pit’s current ore sector was completed in November. In December, the mine said it had reached the goal of 165,000 t/y concentrate production. Kennecott-Utah Copper noted that the mine had averaged 126,000 tons of material moved per day from the date of the slide, with average production levels during that period higher than pre-slide averages.

Clearing 6 million tons of material, a 150-ft haul road was constructed that cut 0.75 miles across the slide making the mine fully accessible again in about 18 months. On top of that 10 of 13 damaged haul trucks were recovered and several have been placed back in operation.

The Mega Machines

The growth of primary excavator and haul trucks during the last half of the 20th century was staggering. Steam shovels mounted on rail evolved into electric powered behemoths mounted on crawler pads. By today’s standard, these shovels appear as awkward with a high center of gravity and an unusually small dipper when compared to the overall size of the machine. Eventually, the stripping shovel eventually gives way to the dragline, which is much more efficient at moving overburden.

E&MJ reports on driverless haul truck fl eets (January 2012).

When it comes to moving large amounts of overburden in a continuous process, nothing compares to the enormity of the bucketwheel excavator and the cross-pit spreader. These machines are used in soft digging conditions and smaller versions of the systems have been modified for use as stackers and reclaimers at port facilities.

The haul truck went through several renditions as it evolved. Electric-powered haul trucks in the 200-ton class were available in the early 1970s. Prior to that there are several configurations of 100- to 200-ton haul trucks. Haul trucks would eventually grow to the 240-ton class in the 1990s and the mechanical drive trucks would gain in popularity. This seemed to satisfy the industry with three- to four-pass loading with the electric shovels and it allowed truck makers to catch their breath as they had reached their limit for the time being.

The 63-in. tire is introduced toward the end of the 1990s and it enables the truck makers to advance the payload to 360 tons. This move forces the shovel maker’s hand and they begin to develop larger shovels capable of loading these trucks with three or four passes. Interesting, electric drive trucks regain their popularity during this period.

More recently, mine owners and truck manufacturers have been working together to launch autonomous systems, where driverless trucks guided by GPS haul ore from the pit to the dump point.

E&MJ Editors 1866-2016

George Francis Dawson (1866-1867)—Not much is known about the first editor of the American Journal of Mining, which later became Engineering & Mining Journal (E&MJ). With a penchant for concise, informative reporting, he guided the early editions of the publication when both publishing and mining were still in their formative years in the U.S.

Rossiter W. Raymond (1867-1890)—Raymond established E&MJ as the American voice of authority for mining and mineral processing. In addition to his publishing career, he served as U.S. commissioner of mining statistics and helped found the American Institute of Mining Engineers (AIME). His office in lower Manhattan became the unofficial center of the American mining fraternity. In his late 50s, he earned a law degree and offers expert testimony on complex mining lawsuits.

Richard P. Rothwell (1891-1901)—Rothwell was co-editor with Raymond from 1874 to1889, and thereafter editor until 1901. He established E&MJ in its early reputation as a journal of mining economics and technology. He was an active sponsor of the AIME in 1871 and was president in 1882.

David T. Day (1901-1902)—Day’s contemporaries agreed that his brief association with E&MJ was almost nominal, and that he soon retired to devote his time to work for which he was well fitted. His career of 28 years in the U.S. Geological Survey earned for him the sobriquet of “father of the Mineral Research Division.”

T.A. Rickard (1903-1905)—Rickard enlisted the financial interest of a large group of mining engineers in the company, who controlled E&MJ editorially until it was sold to Hill Publishing, which was eventually merged to form McGraw-Hill Publishing Co. He promoted a lively discussion of technical topics, notably on ore deposits, mine sampling and pyrite smelting. A master storyteller, he had a distinguished publishing career, which included periodicals and books. Rickard was regarded as a prolific mining writer.

Walter Renton Ingalls (1905-1919)—Ingalls inherited from Rothwell the economic and statistical tradition of E&MJ, and developed the method of market reporting that gained worldwide acceptance for E&MJ’s metal prices. He wrote countless articles on mine and mineral processing technology. During his editorship, the technical scope of E&MJ was broadened to such an extent that he decided to abandon coal mining, and create Coal Age for that branch of the industry.

J.E. Spurr (1919-1927)—Following World War I, Spurr sensed the importance of the international aspect of the mining industry and reflected that conviction in the pages of E&MJ. He expanded the market reporting service and publicized the marketing of metals and minerals. His personal contributions on geological subjects attracted the special interest of the profession.

A.W. Allen (1927-1933)—Allen inaugurated the series of special issues of E&MJ devoted to single great mining enterprises and to important mining areas. During his editorship, the frequency of publication changed from weekly tabloid to the monthly magazine, much like today, and he launched E&MJ Metal and Mineral Markets as a weekly market information and metal price service.

H.C. Parmalee (1933-1943)—Parmalee joined McGraw-Hill Publishing as western editor for Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering, with headquarters in Denver. From 1916-1917, he was president of the Colorado School of Mines. In 1918, he was named editor of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering. In 1928 he was appointed editorial director of McGraw-Hill Publishing Co. He was named editor of E&MJ in 1933. He retired editor emeritus after 34 years of editorial service with McGraw-Hill.

Evan Just (1944-1955)—Educated at Northwestern, Just received a master’s degree in geology from the University of Wisconsin in 1925. His field experience included exploration and examination for mining and oil companies in the U.S., Canada, Brazil and Russia. He joined the E&MJ editorial staff in 1942. Just managed E&MJ during World War II and the subsequent period afterward. He would also serve as the director for strategic materials division of the ECA (Marshall Plan). He was also a vice president with Cyprus Mines and named professor emeritus with Stanford University.

Alvin W. Knoerr (1955-1971)—Knoerr joined E&MJ in 1944 as assistant editor. He became managing editor in 1953 and editor-in-chief in 1955. Regarded as one of the finest editors to serve the mining industry, he was recognized with multiple awards for his work reporting on the technical aspects of mining and mineral processing and regional profiles. Knoerr was a graduate of Wisconsin Institute of Technology and the Missouri School of Mines with a B.S. in Mining. He received a professional degree of mining engineering there in 1941 and was awarded an honorary doctorate of engineering from the Montana School of Mines in l966.

George P. Lutjen (1971-1973)—Lutjen joined the staff of E&MJ in 1949, becoming managing editor in 1955. In 1963, he was appointed general manager of Metals Week. A graduate of Columbia University School of Mines, Lutjen was employed by Freeport Sulphur Co. prior to joining E&MJ. He also worked for a period of time with the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. During 1973, Lutjen is promoted to group director of planning and development for McGraw-Hill Publications Co.’s specialized industry group.

Stanley H. Dayton (1973-1987)—Dayton is appointed editor-in-chief of E&MJ in August 1973. A 1950 graduate of Washington State University in mining engineering, Dayton spent several years working for mining companies in the Northwest. He entered the publishing field in 1954 and joined McGraw-Hill as managing editor of E&MJ in 1964. Monthly, he discussed the issues of the day and defended the mining industry with a commentary column facing the inside back cover of the magazine. Dayton retired in 1987 after a distinguished publishing career with E&MJ.

Lane White (1988)—At the end of 1987, McGraw-Hill sells E&MJ and Coal Age to Maclean Hunter Publishing, a Chicago-based subsidiary of a leading Canadian publisher. In March 1988, White is named editor of E&MJ. He shepherded the publication through the transition. He still contributes to the magazine today. White joined the E&MJ editorial team in 1971 and was first named managing editor of E&MJ in early 1974. He served in that role until early 1983, when he was posted to London as the magazine’s European editor, returning to New York and reassuming the role of managing editor in early 1987.

Robert J.M. Wyllie (1989-1999)—In February 1989, E&MJ promoted Wyllie to editor. An animated Scotsman, he had served as an international editor based in Brussels since 1985. He was a mining engineer who had worked in platinum mines in South Africa and the copper mines in Zambia in the 1960s before he came to publishing. As editor of E&MJ, Wyllie offered a world view with extensive historical knowledge.

Richard W. Phelps (1999-2002)—In January 1999, Phelps was appointed editor-in-chief. He joined E&MJ’s editorial staff as managing editor based in the new Chicago office in September 1989. A graduate of the Missouri School of Mines, Phelps was a mining engineer who had previously advised financiers on mining-related transactions.

Stephen J. Fiscor (2003-Present)—Fiscor joined the editorial team in 1991 as technical editor for both E&MJ and Coal Age. He was later assigned to Coal Age full time eventually becoming editor-in-chief in 2001. After being appointed editorial director for the mining trade journals, he was named editor-in-chief of E&MJ in 2003. He is credited with restoring E&MJ after the drought of the 1990s. He holds a B.S. in mining engineering from the University of Missouri-Rolla and his field experience consisted of five years with a longwall mine in Colorado.

E&MJ’s Supporting Staff

Russ Carter

Managing Editor, E&MJ and Coal Age

Based in Salt Lake City, Utah, Russ Carter has more than 30 years of experience as a technical journalist, and has covered all aspects of the mining, quarrying and construction industries. Prior to joining E&MJ and Coal Age in 1988, he held positions as editor of Intermountain Industry magazine, monthly columnist for Rocky Mountain Construction, and managing editor of Mining Engineering. He has served as a senior communications specialist for firms in the nuclear safety and computer simulation sectors, and has had articles published in Institutional Investor magazine. Carter has received awards for journalistic excellence from the American Society of Business Publication Editors and the Society for Technical Communication.

Simon Walker

European Editor

A graduate mining engineer and mining geologist with more than 40 years of experience, Simon Walker is Mining Media’s European editor. He has been involved with mining journalism since the mid-1980s, and since the early 1990s has been providing research, management consulting, editorial and technical services to an international client base. His interests cover both the hard rock and coal sectors, as well as environmental issues and the socioeconomic aspects of the international mining industry. Based in Charlbury, England, he has traveled worldwide during his career.

Oscar Martinez Bruna

Latin American Editor, Equipo Minero,

E&MJ and Coal Age

Oscar Martinez has two degrees from a prestigious technical college in Chile: English/German translator (1989) and business administration (1992). He was the regional winner of the INJUV awards, granted by the Technical Cooperation Office of the Chilean government in 2003 to encourage enterprising business projects involving innovative e-commerce (business-to-business) applications. His technical background also includes working in coal-fired thermal power plants and mine sites as technical translator and interpreter. Most recently, he worked as a consultant for P&H MinePro Services, Hatch (a mining EPCM contractor) and Escondida (the largest copper mine in the world).

Gavin du Venage

African Editor, E&MJ

Gavin du Venage is a Johannesburg-based business journalist. He has almost 20 years of experience covering Africa, including a stint as a stringer for the San Francisco Chronicle and the New York Times. Most recently, he participated in the launch of The National, an Abu Dhabi broadsheet newspaper. He currently focuses on mining and energy issues, two subjects that are driving African development and changing its fortunes that decades of aid-dependency has been unable to do.

Jennifer Jensen

Assistant Editor, E&MJ and Coal Age

Based in Jacksonville, Florida, Jennifer Jensen is the assistant editor of E&MJ and Coal Age. Prior to joining Mining Media in 2013, she worked as a reporter for newspapers in Tennessee and Florida. During her career, she has earned Florida and Tennessee press association awards for her reporting and writing. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Florida.