The decade begins with lots of promise, but ends with more questions

By Steve Fiscor, Editor-in-Chief

Cortez Gold Mines opens one of the first heap-leach gold mines in Nevada.

The March 1970 edition of E&MJ exclaimed, “That 1969 was a year!” In outer space, man first set foot on the moon. In New York, the Miracle Mets won the World Series. And in its own way the mining industry was in tune with these amazing times.

There still didn’t seem to be enough copper to satisfy demand and the administration in Washington appointed a special subcommittee to investigate copper marketing and determine why there was a big discrepancy between U.S. and foreign prices. A protracted Canadian strike had forced nickel prices to highs of $7/lb. The Free World consumption of primary and secondary lead hit a record high, almost 200,000 tons over the previous year.

But, this would all change and mostly to the detriment of U.S. miners. The 1970s ushered in a new era of environmental awareness. Energy had also become a real concern with the oil embargo. Hoping to jump start the economy, President Richard Nixon decided to free the dollar from the gold standard, which held gold prices fixed at $35/oz for the longest time. To combat smog in the big cities, he would force the auto industry to do away with leaded gasoline, which accounted for about one-fifth of lead’s market.

Toward the end of the decade, the U.S. mining industry began to confront an unfriendly regulatory environment with a different administration as Nixon stepped down in disgrace and President Jimmy Carter took control. Despite the fact that the metal mining business had been developing environmental and safety improvement programs throughout much of the 1950s and 1960s, the American mining industry found itself in a defensive position for the first time as politicians begin to draft new laws and it would only lose ground from then on.

The anti-pollution challenge was everywhere. In Arizona, the press waged a daily crusade against the state’s eight copper smelters. Construction of nuclear plants was curtailed due to public fear of contamination. By today’s standards, there was a lot of pollution and Americans seemed to be in agreement that it needed to be reduced. But, where the real sources of pollution were, and how far it must go to eliminate those pollutants would not be factually determined in the 1970s.

The mining sectors in Australia and Canada, which were developed based on finds in the 1950s and 1960s, were starting to hit their stride. Large mining complexes and the supporting infrastructure have been engineered, constructed and brought into commercial production in a relatively short period of time. Meanwhile, a wave of nationalization swept through Latin America, leading to the expropriation of Chilean mining assets developed by mostly American companies.

On top of all that, many people wondered how much the economy would slow and not whether it will spring back, but when. Real growth in the American gross national product (GNP) seemed to come to a virtual halt in the last quarter of 1969. The automotive industry was exhibiting real pain as it entered 1970 and it accounted for a whole lot of metal back then too—only it was steel, not aluminum.

The mining industry had forgotten the basic principles of supply and demand during the generation that followed World War II. As E/MJ reported record achievements in increasing production capacities at the mines and mineral processing plants, no one appeared to be concerned with a market being saturated with raw materials. By the end of the decade, with a full-blown crisis in the Middle East and worldwide economic issues, reality started to hit home in the mining business.

Editorial Control Changes Hands

Engineering & Mining Journal (referred to as E/MJ back then) was a 200- to 300-page perfect bound trade journal that was published monthly—about twice the size of today’s magazine. Color was being used more frequently, especially on the cover, and for advertising and some sections of the magazine, but it was still mostly black-and-white. In February 1970, long-time E/MJ Editor-in-Chief Al Knoerr was promoted to editorial director. In this new capacity, he was asked to coordinate special editorial projects on the developing new technologies and expanding international coverage and he did that well. Knoerr joined E/MJ in 1944, became managing editor in 1953 and editor-in-chief in 1955.

George P. Lutjen succeeded Knoerr as editor-in-chief. He joined the staff of E/MJ in 1949, becoming managing editor in 1955. Not long after being appointed editor-in-chief, Lutjen announced that Knoerr and E/MJ Art Director Barney Edelman were presented with a Jesse H. Neal award for outstanding journalism in 1969 at a rousing luncheon in New York’s Americana Hotel. The Neal award, given by the business publishers’ national association, American Business Press, is to industrial editors something akin to what the Pulitzer Prize is to general journalists. The issue that earned the distinction was “Canada’s Dynamic Mining Industry” published in September 1969. This was not a new experience for Knoerr. When the Neal awards were re-instituted in 1955, he won his first for “U308-Formula for Profit,” a study of the opportunities and pitfalls in the fledgling uranium mining industry. He won four more after that.

After assembling and publishing a vast collection of articles on different regions and technologies, Knoerr requested early retirement in May 1971 so that he could assume the post of director of communications with the American Mining Congress. Stanley H. Dayton rejoined the E/MJ editorial staff as executive editor. During July 1973, Lutjen was promoted to group director of planning and development for McGraw-Hill Publications Co.’s specialized industry group.

Dayton succeeded Lutjen as editor-in-chief of E/MJ and remained at the post until the late 1980s. A 1950 graduate of Washington State University in mining engineering, Dayton spent several years working for mining companies in the Northwest. He entered the publishing field in 1954, serving in various editorial and sales capacities for mining periodicals. Dayton joined McGraw-Hill as managing editor of E/MJ in 1964. He left the company for a position in industry in 1970. Monthly, he discussed the issues of the day and defended the mining industry with a Commentary column facing the inside back cover of the magazine.

The Mining Scene at the Beginning of the 1970s

Prices for nearly all metals and mineral commodities were trending upward in 1970. Copper producers were planning to expand at an average annual rate of 7.2% during 1970-1973. By 1973, the U.S. was expected to lead the world in copper production with 2.24 million tons, followed by Chile (1.17 million tons), Zambia (921,000 tons) and Canada (856,000 tons). Total world copper production was estimated to be 7.68 million tons in 1973.

Emerging nations were taking control of large copper mining operations. Anaconda agreed to a phased nationalization plan over a 12-year period where the Chilean government assumed 51% control over the Chuquicamata and El Salvador mines. Anaconda held the remaining 49%. Similarly, Zambian President Kenneth Kuanda “invited” Anglo American Corp. and the Roan Selection Trust to sell 51% of its Zambian operations to the government.

|

|

| George P. Lutjen | Stanley H. Dayton |

In the U.S., mining enjoyed a bumper year with an output of $9.68 billion in metals and non-metallics. Free of strikes, U.S. mine production of recoverable copper reached a record high of 1.6 million tons, compared to 1.2 million tons in 1968. Production from Missouri’s new Lead Belt mines was a little slower in materializing than anticipated. As it was, lead mines in Missouri turned out 150,000 tons from new mines, and full-year mine operations churned out more than 500,000 tons of recoverable lead.

Zinc output rose 3% to 546,000 tons. As the year ended, however, zinc found itself in a somewhat “softer” market position than lead. The big story in zinc was disclosure of a major discovery in Tennessee by New Jersey Zinc, a division of the conglomerate Gulf & Western Industries, Inc. It was looked upon as a find that may establish a new zinc belt in Tennessee of similar magnitude and importance as Missouri’s new Lead Belt was to the lead industry of the U.S.

Nevada saw a new gold mine operation begin in 1969 as Cortez Gold Mines broke-in its new 1,700-tpd agitation leach, CCD cyanide plant. With a year unmarked with labor strife in copper, gold staged a comeback with an output of 1.7-million oz, which USBM valued at $72.2 million. The figures indicated an average settlement of a little over $42.47/oz. Silver production advanced to about 40 million oz compared with 32.7 million in 1968. Silver was also beginning to see its market erode as the developing process for photography was using less chemical solutions.

The U.S. was also producing 3.8 million tons of aluminum, 86 million tons of iron ore, 98 million lb of moly, about 17,000 tons of nickel, 40 million oz of silver. Hanna Mining and Cleveland Cliffs increased iron ore production, the first upward revision in eight years.

In Canada, Saskatchewan’s Premier Ross Thatcher tried to bring order out of chaos in potash by imposing a minimum selling price of $18.75/ton and by limiting output to some 60% of a plant’s rated capacity in an attempt to head-off a finding by the U.S. Tariff Commission that muriate of potash was being dumped in the U.S.

Japan, which was sparking mining developments in Australia, Western Canada, South America, the Congo and other scattered areas, estimated that it would have to import about 200,000 tons of copper equivalent in metal, ores or concentrates each year during the next five years. Even after agreements had been consummated with Lornex Mining Ltd. in British Columbia, Bougainville Mining Co. in the Solomons and Freeport Indonesia Ltd. in West Irian, Japan thought it would still be short in procurement by some 100,000 to 200,000 tons of copper resources in 1972 and 1973.

Australia continued as the number one generator of new mining districts. A new nickel belt was extended northward considerably. The nation, according to E/MJ, moved literally from nowhere to a world power in bauxite. And it certainly has become one of the world’s premier iron ore mining areas.

Australia’s Mining Boom Begins

As Australia moved into the second half of the 20th century, few of its people could have anticipated the astounding mineral developments which lay around the bend. Coal and iron were available in quantities adequate to meet domestic requirements and, in the case of coal, to permit modest exports. Australia was among the world’s leaders in production and export of lead and zinc. Although a handful of other minerals added marginally to export income, Australia was a substantial net importer of minerals and there seemed little prospect of changing this situation. Discovery of uranium at Rum Jungle in 1949 (the first of a number of significant uranium finds in Northern Australia) did little to affect the pulse of general prospecting.

Referring to Australia as the Mesabi of the Pacific, E/MJ cites two events that primed the boom. The first was the discovery of iron ore deposits in the Northern Territory and Queensland in the early 1950s. These are now of no immediate importance; their significance lies in the fact that they were quite new in kind and geological environment for iron deposits in Australia, and in the fact that their discovery led to the realization by the government that, with necessary incentives, other deposits would be found. This led to the partial lifting of a long-standing embargo on iron ore exports, a decision which was to have the most dramatic consequences.

The second momentous event was discovery of enormous bauxite deposits in North Queensland in 1955. Dramatically, within the space of 10 years, has been discovery after discovery of new mineral deposits—a number of which had not been previously mined in Australia.

In the 1960s mineral production, ex-mine, increased from $A330 million to $A820 million. The value of these minerals after primary treatment rose from around $A400 million to $A1 billion in the same period. These figures tell only part of the story because, in terms of actual production, the boom is only beginning.

In 1960 when the Australian government relaxed the iron-ore export embargo, the object was to encourage intensive iron ore exploration. By the early 1970s, ore reserves of grade better than 50% iron (Fe) were estimated to exceed 17 billion tons, including 8 billion tons of hematite ore of direct shipping grade (i.e. containing 60% or more Fe). Most of the newly found ore is in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, but other substantial deposits lie in the Northern Territory and in Tasmania. Nine iron ore projects were established—three of world significance. Production of ore totaled 26-million tons, valued at $A200 million in 1968.

As of July 1969, long-term contracts had been written for the supply of 408 million tons (worth some $A3.3 billion) of lump, fines or pelletized ore to Japan. More contracts are being written and other market outlets are being sought. Australia is expected to be supplying 30% of Japan’s iron ore needs in less than a decade.

In the early 1970s, 80% of Australia’s iron ore exports were in the form of unprocessed ore but it is expected that an increasing proportion of the growing export trade will be in processed form, either pelletized or metallized agglomerates. Three pelletizing plants are already in operation.

Bauxite and alumina production soars. Since discovery of large bauxite deposits at Weipa in North Queensland in 1955, there has been a spectacular expansion in the Australian aluminum industry. By the mid-1970s, Australia is expected to become the world’s second largest producer of bauxite and possibly the third largest producer of alumina.

Australia’s known reserves of bauxite are vast—on the order of 3 billion tons, representing 35% of the world’s reserves. Production of bauxite in 1968 totaled nearly 4.9 million tons while alumina production totaled 380,000 tons. Alumina production capacity by 1970 has now reached 1.8 million tpy, and announced plans indicate that annual capacity will be at least 3 million tpy by 1972. Exports of bauxite and alumina are already substantial and will significantly increase over the next few years. Exports from projects already announced will lift the figure for exports of bauxite, alumina and aluminum to more than $A350 million annually by 1980.

Of all the important post World War II Australian mineral discoveries, none had a more bullish impact than Western Mining Corp.’s (WMC) nickel strike at Kambalda in Western Australia in 1966. Prior to this, Australia had no known nickel deposits. It attracted the attention of numerous nickel miners. In 1970, WMC was currently the sole producer and exporter of nickel concentrates having commenced operations in June 1967. Its proven reserves totaled 14.3 million tons of ore averaging 3.4% nickel. Some 4,500 tons of nickel in concentrates were produced in 1968 and the company will be producing at the rate of 30,000 tpy by 1970. A nickel refinery at Kwinana, Western Australia, (capacity 17,000 tpy) was scheduled to start in 1971, and the company is investigating feasibility of erecting a smelter with a capacity of about 20,000 tpy of nickel matte.

The June 1971 cover of E/MJ uses color photography.

E/MJ reported that given the acute world nickel shortage and growing consumption, no difficulty was anticipated in disposing of Australia’s expanding nickel output. WMC signed contracts to sell 40,000 tons of nickel in concentrates over 10 years to Japan and 4,500 tons over three years to Canada.

Already the world’s largest producer and exporter of lead and a principal producer and exporter of zinc, E/MJ reported that Australia can be expected to continue as a major supplier of these minerals. Capacity of the Rosebery (Tasmania) mine of electrolytic zinc was to be doubled to 600,000 tpy of ore. At Beltana (South Australia) nearly 1 million tons of high-grade Willemite ore had been proved and a further discovery had been made nearby. Further exploration had commenced on the promising Woodcutter’s (N.T.) lead-zinc-silver prospect.

At Port Pirie, an installation which recovers zinc from lead slags and had a capacity of 40,000 tpy of zinc had started operation. Substantial new lead-zinc-silver deposits on Mount Isa’s northern leases were to be developed, and production from these was planned to begin in seven years. A Mount Isa subsidiary was making a detailed study of large lead-zinc orebody at McArthur River but metallurgical difficulties are yet to be overcome.

Australian copper production over the last five years had been fairly static, but a substantial increase was to be expected during the next five. Following the completion of a $A130 million expansion program, Mount Isa had announced plans to spend $A4.5 million more on sinking a major new shaft to be in operation by late 1971. Production of concentrates commenced at Cobar in 1965, and output was expected to reach more than 20,000 tons of contained copper by about 1974. Mount Lyell had commenced a $A30 million expansion program which will increase its production to 24,000 tons of copper in concentrates in 1973.

The vast capital investment required to exploit these resources, and the direct and multiplier effects of that have contributed in a major way to the Australian economy. Large sums were also being spent to develop processing facilities for many of the newly found minerals. Foreign investment was playing a vitally important role in mining exploration and development. E/MJ reported that $A346 million, nearly 40% of total foreign private capital investment in Australia in 1967-1968, was American. The names mentioned included Amax, Asarco, Anaconda, Bethlehem Steel, Cerro Corp., Cleveland Cliffs, Continental Oil, Cyprus Mines, Freeport Sulphur, Hanna, Homestake, Kaiser, Kennecott, National Lead, New Jersey Zinc, Peabody Coal, Phelps Dodge, Pickands Mather, St. Joseph Lead, Sun Oil and Utah Construction.

The great Australian mining boom would result in the output of huge quantities of critical materials such as iron ore, bauxite and alumina, titanium bearing ores, nickel and coal, which would help to meet a fast growing world demand. While the estimates of iron ore reserves were said to be in the vicinity of 17 billion tons, E/MJ said the figure is misleading as it refers only to high-grade ore. The total ore tonnage in the Pilbara region alone could be as high as 100 trillion tons, a great deal of which is equal to or better in grade than the average North American ores where total reserves, commonly acknowledged to be the largest in the world, total 150 to 250 billion tons, grading around 30% Fe.

Hamersley to Become World’s Largest Iron Ore Producer

In March 1970, E/MJ reported that Hamersley Holdings Ltd. would spend several hundred million dollars over the next three years to expand its iron ore mining activities in Western Australia, including the opening of a new open-pit operation at Paraburdoo. This expansion was expected to make the company the largest iron ore producer in the world.

Hamersley Holdings currently produced 17.5 million tpy of iron ore. The company planned to boost this output by 20 million tpy (to 37.5-million tpy) by 1974. The expansion program would be based on total reserves held by the firm, estimated at the time to exceed 5.1 billion tons.

The vast expansion plans included boosting the output of the existing Mount Tom Price mine by 5 million tpy to 22.5 million tpy by the end of next year. Also, the development of a $A250 million mine at the high-grade hematite orebody at Paraburdoo, 35 miles south of Mount Tom Price, would result in the extraction of 5 million tpy of ore by 1972, and 15 million tpy by 1974. At Paraburdoo, standard open-pit selective mining methods would be used. The equipment would be similar to that in operation at Mount Tom Price. Planned installation at the new mine includes primary and secondary crushers, loading ancillary facilities to prepare and load lump and fine ore. There would be about 65 miles of heavy-duty gage line built to link Paraburdoo with the existing Mount Tom Price-Dampier railway. At East Intercourse Island, a new port will be developed to handle ships to 150,000 tons, and the existing town of Mount Tom Price will be expanded. A new town would also be established at Paraburdoo, and there would be provision of housing for Hamersley employees at the town of Karratha, now being built by the Western Australian government.

Hamersley said that it is pressing on with the development of technology and commercial prospects of Himet, a metallized agglomerate, with the intention of submitting to the government proposals for the production of this material.

According to Hamersley directors, further large-scale expansion was already on the drawing boards. This new program would be carried out after the present one is completed and will raise the company’s output by another 15-million tpy. The firm made its first iron ore shipment in August 1966. Initially, capacity was about 5 million tpy, but it has grown rapidly, to reach in less than four years the current 17.5 million tpy.

Nickel Strikes Wear On

E&MJ September 1969 p. 33—August drew to a close, the nickel market neared a crisis point. The strike of International Nickel’s Ontario operations (70% of company production) ground through its seventh week and negotiations had been broken off. On top of this, Falconbridge was struck on August 21. The United Steelworkers’ strike at Inco is costing 1 million lb/day; the Mine & Smelterworkers’ walkout at Falconbridge 200,000 lb/day.

The consumer stock position varies company to company, but even the best-off are dangerously low. Generally, the steel mills have the best stock position. However, some of these stainless producers have already been forced to curtail production.

Defense-rated orders are still being met through Inco’s Manitoba mines and Hanna’s Riddle, Ore., ferronickel output. Inco has pushed Manitoba production up from its normal 8-million-lb/month capacity to more than 9-million lb/month.

Canada’s Dynamic Mining Industry

As it does today, the mining industry recognized Canada’s favorable exploration climate and the notoriety of Canadian miners abroad. In the aforementioned September 1969 special report, for which Knoerr received a Neal Award, E/MJ showcases the Canadian mining industry. “This is the story of Canadian Mining as it has never been told before,” E/MJ said.

At the time, Canada was ranked the third largest producer of minerals in the world—topped only by the Soviet Union and the U.S. Canada’s mineral output was expected to be a little more than $5 billion, which is a sum that kind of boggles the mind. It is the cumulative result of an average annual growth of some 9% a year since the days of World War II. As a developed area, mining was proportionately far more important to the Canadian economic scene than it is in other developed areas of the world.

The piece opens with an introduction from the Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. He acknowledged the remarkable achievements made by the Canadian mining industry and the fact that they are contributing to the growth of this industry in developing nations.

A section titled Canada the Producer documented mining companies and projects addressing current performance, future expansion plans and exploration targets.

Inco was growing nickel production, principally in the Sudbury district of Ontario, and most recently in the Manitoba mining area. During 1968, the company pushed forward its major capital program—the largest in its history-to expand its nickel producing capacity in Canada progressively to a rate of more than 600 million lb/y by the latter part of 1971, an increase of more than 30%.

Falconbridge Nickel Mines, which celebrated its 40th anniversary in 1968, was turning its attention to laterites. Moving ahead with its greatest expansion phase, the world’s No. 3 nickel producer, accounting for about 10% of the world’s output, had aims of increasing its production from recent rates of about 75 million lb/y to 180 million lb/y by 1975—roughly 15% of the expected world production at that time.

Similar to other major nickel producers, Falconbridge realized that sulphide nickel deposits will not be adequate to supply all the nickel required in the decades to come. So attention now turned at an almost feverish pace toward the tremendous nickel reserves locked up in the laterites—the highly weathered, residual surface deposits which are widespread in the tropical and warmer belts of the world. In April 1969, the company announced a $180 million lateritic nickel project in the Dominican Republic: The property held by Falconbridge Dominicana, C. por A. (or Falcondo), contains 64 million tons of surface-minable lateritic nickel. The ore would be treated by a new metallurgical process developed by Falconbridge’s laboratories in recent years—yielding an iron-nickel product called ferronickel, which is assuming greater importance in the steel industry.

The Canadian piece also detailed the historic developments with Iron Ore of Canada (IoC). The decision to proceed with the development of IoC opened up Canada’s famous North Shore extending from Quebec to Labrador and resulting in more than a $1 billion investment in iron ore and processing. Driving the 360-mile railroad through bush, swamps, lakes and hardrock tunnels was a staggering financial undertaking presenting almost insurmountable construction obstacles.

With modern techniques, extremely competent staff, thorough planning, and some luck, Texas Gulf Sulphur Co. put its huge concentrator near Timmins, Ontario, on full production just four years after uncovering Kidd Creek, Canada’s miracle base metals deposit.

Since making the announcement of its Kidd Creek discovery, TGS, operating through Ecstall Mining Ltd., put the open pit into production at a rate of 12,000 t/d (on a five-day week); built an automated concentrator that treats about 10,000 tpd of ore containing zinc, copper, lead and silver; and linked the two by a 17-mile railroad. The company decided to build an electrolytic zinc smelter and sulphuric acid plant next to its concentrator at Hoyle. According to Texas Gulf, the $50 million complex—built, owned and operated by Ecstall Mining and one of the largest of its type—would handle about half of the Kidd Creek zinc concentrates, and will have provisions for future expansions.

Under the muskeg near Timmins, Ontario, Texas Gulf mines zinc-copper-lead ore at Kidd Creek.

By 1980, the Kidd Creek pit would bottom out at 790 ft below the original surface, and mining would then be done underground exclusively. To ensure a smooth transition from pit to underground, TGS would soon start sinking a shaft, have the sub-pit workings turn out about 1.8 million tons of ore by late 1973, and gradually take on a larger and larger portion of the mine’s output.

To do justice to the orebody, TGS came up with an ultramodern concentrator that incorporates the latest word in automation and process control. The company felt that since the concentrator was working around the-clock all year in a region where winter temperatures sometimes dropped into the -50°F range, the plant’s three major operating sections—crushing and grinding, flotation, and concentrate handling—should be under one roof. The company therefore built one that had an area of 7 acres.

When Great Canadian Oil Sands Ltd. reviewed the current status of the $235 million, 45,000-bbl-per-day oil sands project in the Athabasca field of Alberta in May 1969, they referred to the venture as “The World’s First Oil Mine.” It is truly a mine in the sense that some 4-million yd3 of overburden had to be stripped by truck and shovel before the two bucketwheels could start mining the oil sands at a planned rate of 100,000 tpd.

As might be expected, startup problems of this huge prototype operation were formidable. Since no convenient power lines were available in this remote location 650 miles south of the Arctic Circle, the energy to run the bucketwheels, each with 3,700 hp and the 100,000-tpd extraction plant, had to come from the oil sands. Coke extracted in the upgrading process fires boilers, which feed steam to the 76,000-kVA turbine plant. The pioneering large 750,000-lb boiler system created extensive problems now being resolved. Similarly, operating the bucketwheels in normally sticky oil sands under extreme cold conditions plus occasional lenses of rods created serious wear problems for the bucketwheel teeth.

Rapidly increasing production rates at the close of 1968 indicated that these operating problems were nearing resolution. However, in June 1969 GCOS announced that it would spend more than $4 million to smooth out production cycles. “In a nutshell, we are surface mining the sand, extracting the oil from it in a hot water separation process, returning the clean sand to the lease, upgrading the oil on the site, and piping it south in a 266-mile, 16-in. pipeline which we constructed to tie in with the Interprovincial Pipeline,” the company explained. The GCOS crude oil was a high-quality, low-sulphur charge stock that fit well into conventional cracking as well as being ideally suited for hydrocracking.

In neighboring Saskatchewan, 10 mines were producing a total of 7.4 million tpy of potash. More than half of the mines were constructed and commissioned in the late 1960s.

Denison Mines Ltd. was one of the few uranium companies to survive the post-boom era of the 1960s, which was described as a grey time between the military market for uranium and 1970s industrial market for nuclear fuel.

Denison’s mine and mill in the Elliot Lake area of Ontario have operated continuously since 1957, and have produced nearly 50 million lb of uranium concentrates. Although growth and diversification continued, the Denison orebody, with 300 million lb of uranium oxide still to be mined, was the company’s greatest asset and the real key to growth in the 1970’s.

Denison was optimistic about growth of the uranium industry to supply fuel for nuclear power plants, which would be required by industrial nations of the world. The development and growth of the Canadian minerals industry in a stable government and public climate, which recognizes the unique problems of this industry has been of immeasurable value to the whole Canadian economy and society.

Nationalization Sweeps Latin America

A wave of nationalism swept through Latin America, causing grave concerns for international mining firms. It left a number of proposed major mine developments hanging in limbo and raised many uncertainties with regard to reinvestment in established operations.

In April 1969, Anaconda caved to pressure and agreed to a two-stage nationalization over 12 years of its Chile Exploration Co. and Andes Copper Mining Co. The plan, if approved, will “Chileanize” Chuquicamata and El Salvador at the start of 1970 and fully nationalize them no earlier than 1973 and no later than 1980.

In May 1969, the pending $180 million nickel laterite project of Exploraciones y Explotaciones Minera Izabal, S.A. (Exmibal) became a political football in Guatemala with local citizens calling for reappraisal of lengthy negotiation, which had come close to a conclusive stage. Since it was organized in June 1960, Exmibal (80% International Nickel Co. of Canada Ltd. and 20% Hanna Mining Co.) had sunk $15 million in geologic study, feasibility, engineering and site preparation.

The Exmibal crisis came right on the heels of Chile’s well publicized announcement earlier in May that it intended to seek part ownership in all of Anaconda’s mining-processing holdings there, and a bigger share of the profits now being generated by copper sales on the high LME price from all Chilean production. In all probability, this situation will have an impact on all copper mines whether Chileanized or not.

The flare-ups in Chile and Guatemala were part of the pattern of the bumpy going for mining in Latin America. In Peru, for example, the expropriation of International Petroleum Co. had an unsettling influence on mining executives. Two major projects were pinned down in the negotiations stage—Southern Peru Copper’s Cuajone development and the Andes Mining’s Cerro Verde project. Andes Mining was a subsidiary of Anaconda. Both projects were in the plus $100 million class. Blessed with several other large copper porphyry deposits, Peru had not come up to its potential as a world supplier of copper even though its approximately 200,000 tpy output ranks it fifth in the free world.

Elsewhere in Latin America, both Kennecott Copper and American Metal Climax Inc. were hung-up on negotiations on major copper projects in Puerto Rico. Amax’s subsidiary sought to mine two orebodies—one of 83 million tons, the other of 75 million tons of 0.8% copper. Kennecott’s Cobre Caribe had a single orebody estimated at 177 million tons of 0.64% copper. Cobre Caribe was planned for about 32,000 tpy and Ponce for 36,000 tpy when negotiations stalled.

The current pressures within Chile for a greater share of the profits from the country’s copper operations were simply an extension of a pattern promised by President Eduardo Frei Montalva when he took office in 1964, and formally begun by him two years ago.

As the first enactment of what President Frei called “Chileanization”—any percentage of government ownership in a private company’s operation—control of El Teniente, Kennecott Copper’s huge underground mine, passed into the hands of the government in 1967. A company-Chile partnership was formed; through a government copper corporation, the country acquired 51% of El Teniente, Kennecott holds the remaining 49%.

In addition to El Teniente, the Frei administration negotiated participation contracts with the two other U.S. companies carrying out large-scale copper operations in Chile. For $22 million, Chile got a 25% interest in Minera Andina Copper Co. (Rio Blanco mine), from Cerro Corp. In the Anaconda agreement, the company retained 100% of Chuqicamata, El Salvador and La Africana, but would take Chile as a 25% participant in new mines such as Exotica.

But this was only the beginning. During the past three years, the clamor within all areas of Chile’s political structure had been for greater government participation in the copper industry. Finally, responding to the general mood in the country—a wave of opinion fed, no doubt, by sustained high copper prices on the London Metal Exchange, where most of Chile’s copper is sold, and perhaps further fired by recent government-oil problems in Peru—President Frei, as part of his state-of-the-nation address in May, said Chile would seek an ownership interest in the remaining Anaconda mines (Chuquicamata and El Salvador) and a larger earnings share from the copper mining operations of all companies in Chile.

The agreement finally hammered out by Chilean and Anaconda officials amounts to progressive nationalization of Chuquicamata and El Salvador. President Frei announced at in a nationwide broadcast on the evening of June 26. Anaconda later said the nationalization plan did not apply to the Exotica pit now being stripped and nearing the production stage. The latter was planned for a mining rate of 100,000 tpy of copper equivalent in ore with the output undergoing treatment at Chuquicamata.

On January 1, 1970, assets and liabilities of the two Anaconda subsidiaries were to be transferred to two new Chilean companies. The government purchased 51% of the shares for an approximate $200 million price tag, which represented the book value. The amount was payable in U.S. dollar bonds bearing 6% tax free interest in semiannual installments over the 12-year period.

Chile purchased the remaining shares of the two new companies on completion of payment of 60% of the unpaid balance of the first 51%, and in no event before January 1973 nor later than the end of 1981. The purchase price per share for the 49% interest was determined by multiplying average annual net earnings from January 1, 1970, to the date of purchase by 8 for 1973, 7.5 for 1974, and reduced progressively to a minimum of 6 by 1977 or later.

Anaconda, according to reports, had favored expropriation rather than submit to majority control by Chile. It said that the action to “nationalize by agreement was taken to avoid expropriation by legislation.” In 1968, Chuquicamata produced 307,000 tons, El Salvador 95,000 tons and La Africana 4,800 tons of copper.

A great build out continues as can be seen on the January 1978 E/MJ cover.

Chile Nationalizes Foreign-owned Copper Mines

E&MJ Aug 1971—Chilean President Salvador Allende Gossens in July 1971 signs the constitutional reform passed by the Chilean Congress the day before, nationalizing large copper mines in which U.S. companies have invested an estimated $700 million. This move allows the Chilean State Copper Corp., which will later become known as Corporación Nacional del Cobre (Codelco), to assume full control of the nationalized mines. Affected U.S. companies are Kennecott, Anaconda, and Cerro Corp. The mines involved are EI Teniente (Kennecott); Chuquicamata, El Salvador, and Exotica (Anaconda); and Andina (Cerro). These operations produce about 80% of Chile’s copper—the nation’s main export—which amounts to 12% of world production.

The compensation to be paid the companies will be determined by an audit made by Chile’s controller-general, with review of the final settlement by a special tribunal.

President Allende has been assuring the country that copper production is holding its own. But the men in the mining offices are telling a different story—one which becomes bleaker as months pass. Observers of the Chilean situation, meanwhile, say that although the nationalization of copper has great popular appeal, the hard fact is that the government is inheriting a cripple.

Kennecott, which a couple of months ago revealed that 77% of its administrative personnel at El Teniente had quit, reports that more resignations have come in over apparent disgust with the lack of discipline and political harassment. “We try to keep pace, but we’re forced to hire replacements with much less experience,” said a company official.

A lamp shade and iron bar were pulled out of the thickener at the smelting plant—the latest of a series of “accidents” which have cost millions of dollars in production since the beginning of the year. Coupled with a 4-meter snowfall, this brought production to a near halt for three days in June.

Despite government claims that this year’s copper yield is running ahead of last year, a Kennecott official said, “The direction has been all downhill.” Production recently dropped to below 300 tpd—down from an average of 300 to 350 tpd earlier in June. June production was put at 10,500 tons per month, as compared with 11,500 tpm in May and an average of between 17,000 tpm and 18,000 tpm in 1970.

Kennecott officials estimate that when year-end rolls around, production figures will show a “considerable” drop compared with 1970. Such a drop becomes dramatically amplified, considering the titanic copper expansion program which was expected to jump El Teniente’s production to 280,000 tpy. Rough figures for the first semester, according to Kennecott, reveal a yield of some 77,000 tons—about 25% of last year’s output at this time.

A Kennecott official estimates that 1 lb of refined copper costs the mixed mining company “close to $0.50”—almost double the year’s opening cost. The reasons are fairly clear-cut: While the payroll has remained almost numerically the same, the government has forced stiff pay increases; the government has fixed the exchange rate which steadies the dollar at an unrealistic 14.3 escudos; and production has been crippled.

Anaconda reported that production “isn’t picking up any” and remains about the same as last year. A Chuquicamata official said the mine is running about 12,000 tons behind last year. An Anaconda executive said year-end figures will probably show production somewhere around 300,000 tons. Copper expansion projections were 390,000 tons.

Anaconda appears somewhat cut off from hard information, but an official said that there has been a substantial increase of personnel at Chuqui. Payroll increases at El Salvador and Exotica haven’t been nearly as dramatic as elsewhere, he said. A Chuqui government official said 600 new men had been hired since the beginning of 1970. At the end of the scale, a Codelco spokesman says the only replacements at the mine have been 54 technicians and engineers filling in for Americans.

Cost-per-pound figures have increased, said Anaconda officials, but they claim not to know much. Codelco’s people say such information is “confidential.”

Heap Leach Operations Begin at Cortez

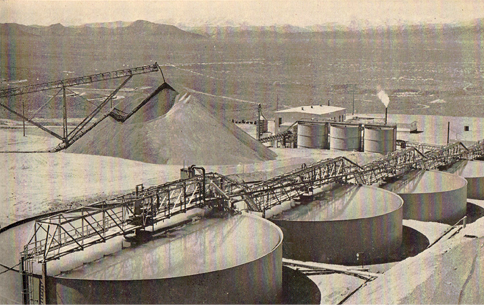

E&MJ July 1977—For more than seven years, Cortez Gold Mines has been successfully operating heap leaching circuits for low grade gold ores in conjunction with a conventional 2,300-tpd milling operation at its Nevada mine sites. A total of 10 million tons of ore has been processed, one-half by heap leaching. Additional ore in the district offers potential for continued production.

Early in the Cortez operation, management recognized that a substantial tonnage of subgrade ore would have to be removed during normal mine operation. In 1969, Cortez started work to develop technology for recovering the gold values in this ore. At the same time, the U.S. Bureau of Mines Salt Lake Research Center was performing small scale heap leaching tests on a number of gold ores. The technique appeared to be a logical choice for Cortez, and the company inaugurated pilot testing at that time. Commercial scale heap leaching of the oxidized limestone ore from the Cortez deposit began in 1971.

Early in 1973, when Cortez reserves were exhausted, properties at Gold Acres, 8 miles from the Cortez plant, were placed in production, extracting a fault breccia ore of ground-up limestone, chert, and shale with a high percentage of clays. Economics again dictated heap leaching of the low grade ore. High grade ore was trucked to the Cortez plant for milling. A carbon recovery circuit was constructed at the Gold Acres site to process pregnant heap-leach liquor.

The integrated heap leaching and carbon recovery circuit for gold required a minimum of operating labor. The major costs of the operation were power, reagent requirements, pad preparation, and leach haulage.

Gold production from the heaps was monitored by sampling, assaying, and measuring each effluent flow. Truck counts during the leach haul and survey measurements of the heaps provided tonnage figures, and blasthole assays and portable lab assays were used to determine the grade of each heap. This information provided enough data to calculate gold recoveries on each heap.

Leach extraction and ore character varied, depending on the area mined. The clayey Gold Acres ore averaged 50% extraction. By contrast, the “blocky” Cortez leach ore averaged 65% extraction. The integrated heap leach and carbon recovery operation remained very profitable as long as Gold Acres was mined.

New Jersey Zinc Discovers Important Orebody

E&MJ February 1969 p. 120—The New Jersey Zinc Co. announced that it has discovered a major zinc deposit in middle Tennessee. Analysis and projections of data on recent ore grade penetrations indicate between 13 and 50 million tons of ore averaging between 5% and 10% zinc. The deposit, which has not been delimited, underlies a 4-sq-mile section of an area of several hundred square miles where significant mineralization has also been encountered by wide-spaced drilling. The company holds mineral leases on acreage in excess of 500 sq miles in the area.

Apparently, initial wide-spaced drilling with holes 5 to 20 miles apart indicated at least five widely spaced locations in which significant mineralization in favorable geologic environment justified closer-spaced drilling. This was undertaken at one of these locations, resulting in the discovery of mineralization of ore grade and thickness. Closer-spaced drilling has been scheduled, but has not been carried out yet, at the other locations.

New Jersey Zinc manager of exploration William H. Callahan has directed the project from its original conception. He said that geologically there is no reason not to find at the other locations ore occurrences similar to that discovered at the first location drilled on closer spacing. He added that, in view of the geologic setting, the potential of the discovery can well be that of a new major zinc district involving several hundred million tons of mineable ore.

Callahan believed that New Jersey Zinc will easily more than double its sulphide ore reserves, with the added reserves having a grade considerably higher than the average of its present sulphide mines.

New Jersey Zinc currently mines some 3 million tpy of ore from its mines, supplying about 75% of the feed required for its smelters, the remaining quantity being purchased from mines outside the U.S. The Tennessee discovery indicates the possibility of mining operations there that not only would make the company entirely self-sufficient in smelter feed even taking into account that some existing mines may be exhausted over the next several years, but could also make zinc concentrates available for sale to other U.S. smelters who depend on foreign sources for supplies.

Our Man in Havana

Our man in Havana and numerous other spots in Cuba, turned out to be News Editor Serge Delinois, after he half-jokingly suggested to a news source at Cuba’s mission to the UN that he do an in-person report on mining in Castro Country. Before he could say “Juanito Robinson” in his flawless Spanish, he was promised a visa. Some 30 days later, which included getting State Department permission and paper shuffling in Mexico, Serge was in Havana.

“The red carpet was rolled out,” said Serge without even blushing for the pun, “and a government guide was strictly optional.” He made the scene at Matahambre on the western end of the island and then drove the scenic route to Oriente Province on the eastern end to take in Nicaro and Moa.

In some ways this is atypical of E/MJ’s usual show and tell reports, Serge was not allowed to use his own camera near the coast which is of course where the mining is, and, in some cases, future plans for development simply had to be taken at face value. But, since few tourists are trotting around Cuba these days, we are passing along en todos, all that Serge saw and heard on his unique visit.

One interesting sidelight was his startling reception in one of the offices of the Ministry of Mines. As Serge walked through the door his host greeted him with the question, “Aren’t you the man who wrote the bismuth review in E/MJ last year?” He had recognized Serge from his picture at the top of that review, which means that some copies of E/MJ really get around, because we have no subscribers in Cuba.

US Regulations Increase

During the 1970s, Washington began to regulate mining and other industries. Congresses passes the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969, generally referred to as the Coal Act, and it was enacted into law by the president of the United States on December 30, 1969. This legislation formed the Mine Enforcement and Safety Administration (MESA), which would later become the Mine Safety and Health Administration. For now, the decision had little impact on metal miners, but that would change with the Mine Act in 1977. Other policies would create the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Energy and the era of red tape began.

In January 1977, E/MJ reported that proposed new rules from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) were the first in a series of regulations to be developed under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act. This act brought some 473 million acres of federal land under a new management mandate for continued federal ownership, and replaces more than 3,000 public land laws.

Under the new proposed regulations, it was necessary to file annually a notice of intention to hold the claim; an affidavit of assessment work performed on the claim; or a detailed report concerning geological, geochemical, and geophysical surveys conducted on the claim, whichever is applicable to the situation.

By March 1977, the new crowd in the capital charted puzzling courses. From all current signs, the Carter administration would present an energy policy next month revolving around forced conservation measures, designed to eliminate wasteful use (a good tactic if evenly applied). But there had been little to signal a greasing of the skids for development of energy resources-sorely needed to divert the U.S. from a collision course with economic disruption. No easing of disincentives standing in the way of new production had been mentioned; in fact, new roadblocks popped up. Meanwhile, a growing body of economic experts worried about the specter of renewed inflation resulting from President Carter’s economic stimulus package, alterations that Congress might make in it, and a projected ballooning of the budget deficit.

Events of the month included a Business Roundtable plea for relief from government interference in business. Rep. Morris Udall (D-Ariz.). chairman of the House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee, announced that a staff draft of a bill to repeal the 1872 Mining Law would soon be ready. Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus replied during questioning before the House Interior Committee that U.S. citizens should have the right to say where mining should take place and where it should not. He also favored strong strip mining legislation.

Sen. Edmund Muskie (D-ME) introduced three bills to amend the Clean Air Act, two of them containing provisions to allow no significant deterioration of air quality (S. 252 and S. 253). Sen. Lee Metcalf (D-MT) introduced a tough bill for surface coal mine control and reclamation (S. 7), which the American Mining Congress said would effectively prohibit opening of open-pit mines west of the 100th meridian, a north-south line roughly bisecting the Dakotas and Texas. Bill S. 7 would have an impact on underground coal mining also.

More safety legislation was dumped in the hopper. Rep. Joseph Gaydos (D-PA) introduced H.R. 2060, the Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977, which would amend the Federal Metal and Nonmetal Mine Safety Act. Among other provisions, H.R. 2060 would authorize representatives to inspect all mines subject to the act; provide for transfer of MESA from the Interior to the Labor Department; and eliminate mandatory usage of an advisory committee in promulgating new regulations.

The Federal Register of February 4, 1977 published mandatory standards for rollover protective structures for scrapers, haulers, tractors and other equipment. and established installation schedules ranging from August 4, 1977, to June 5, 1978, depending on the age of the equipment.

Several million acres more of public land were proposed for non-mining status, most of them in Alaska, although chunks of California also were being considered. H.R. 39 and S. 500, which were nearly identical, would designate about 114 million acres of Alaska as units of the National Park, Wildlife Refuge, and Wild and Scenic Rivers systems. This would close the lands to entry under the mining laws and prevent mineral leasing. H.R. 39 is in Rep. Udall’s House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee, while Sen. Henry Jackson’s (D-WA) Interior and Insular Affairs Committee guided S. 500. Sen. Alan Cranston (D-CA) introduced S. 66, S. 67, and S. 88, which provided additions to wilderness areas and national parks in his home state.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service added 41 species of crustaceans, snails, and fish to the list of threatened and endangered species, many of them living in phosphate, coal, and other mining country. “And the nation shivered while awaiting the Carter administration’s brave new energy policy, which seems destined to reduce the role of nuclear power,” E/MJ chided.

The U.S. Department of Energy, signed into law by President Carter on August 4, 1977, took over all functions of the Federal Energy Administration, the Energy Research and Development Administration, and the Federal Power Commission. It assumed the Bureau of Mines’ responsibility for fuel supply-and-demand analysis and data gathering; research and development for more efficient production technology for solid fuel minerals—except research on mine health and safety and on the environmental and leasing consequences of solid fuel mining, which remained with Interior Department; and coal preparation analysis. The act created a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, an Energy Information Administration, and an Economic Regulatory Administration, to be headed by presidential appointees.

Air Pollution Cooling Off Earth, Will Change Climate if not Checked

E&MJ February 1969 p. 120—The world’s climate has shown a cooling trend since 1940 as a result of increased smoke and dust pollution, and major climatic changes will result if the situation is not checked. This warning was issued in December by a leading climatologist to the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Reid A. Bryson, of the University of Wisconsin, pointed out that the industrial revolution is still under way, and every year more smoke, carbon dioxide, dust, and other pollutants are dumped into the already overburdened atmosphere. “The trend of world temperature in this century appears to be directly related to the trends of atmospheric carbon dioxide content, and atmospheric turbidity or dustiness,” he said.

Increased carbon dioxide tends to raise atmospheric temperatures and turbidity tends to lower temperatures, he pointed out. “Since 1940 the effect of the rapid rise of atmospheric turbidity appears to have exceeded the effect of rising carbon dioxide, resulting in a rapid downward trend of temperature,” Bryson continued. Both cities and rural areas create dust and smoke in the atmosphere. There are millions of square miles of rural land with at least a seasonal smoke or dust problem. Also, winds carry the polluted air to all regions of the world.

Brazil, Southeast Asia, and Central Africa have a blue haze, probably smoke from agricultural burning, and Africa, Arabia, India, Pakistan, and China have a brown haze of blowing dust from dry soil and deserts. In many areas, Bryson said, the high pollution level is so constant that it no longer attracts attention, either from residents of the area or from local meteorologists.

That the dust is largely man-made is shown by the fact that 14 parts per billion of the dust falling on the Caribbean island of Barbados is DDT, indicating that the dust has blown from tilled fields. Industrialization, however, has resulted in the most striking pollution increase. Soviet cities, for example, have increased the smoke content of the air over the Caucasus 19-fold since 1930. In recent years, turbidity of the air over Washington, D. C., bas gone up 57%. Over Switzerland, it has increased 88%. There was a 30% increase in turbidity over the Pacific between 1957 and 1967. Smoky days in Chicago rose from 20 per year before 1930 to 320 per year in 1948; recent decreases are due to increasing frequencies of north winds which blow the smoke over areas other than Chicago.

The 1970s End With More Questions than Answers

For copper, 1979 was a mixed bag. Prices had worked their way back to a profitable level after four years of depression. On the negative side, producers clearly lost control of the market, while speculators wreaked havoc on copper prices—driving them up wildly only to see them quickly dissipate. Mine copper production had shrunk to 6.1 million mt in 1979 from 6.3 million mt in 1977. The U.S. was still the leading producer of mined copper (1.5 million mt), followed closely by Chile (1 million mt) and Canada (620,000) and Zambia (585,000). At the start of 1980, copper markets remained extremely volatile.

Major aluminum producers reported record profits, exceeding highs established in 1978. Return on invested capital increased to14%-18%, and announcement of new capacity expansions for 1983-1984 period increased. The profit performance of the aluminum industry was again superior to that of the other metal industries. Total U.S. aluminum supply, increased 0.7% to 7.5 million tons in 1979. Worldwide production grew to 13.2 million tons from 12.8 million tons.

World production of refined lead advanced 1.4% in 1979, matching the compound growth rate for the period 1972-1979. Production in the U.S. declined slightly to 590,000 tons, an amount representing 21% of free world mine production. Demand and prices for zinc fell, reflecting the weakening state of the auto industry, higher interest rates and the leveling off of construction activities.

A new E&MJ logo appears on the September 1979 edition.

The same issues, energy and the crises in the Middle East, were having the opposite effect on iron ore by dragging steel consumption down. Output of raw steel worldwide had increased steadily since 1974, culminating in a world total of 745.3 million mt in 1979, an all-time high. As the 1980s approached, experts believed that North American and European steel markets would see a decline 5% to 6% in raw steel output. The decline for Japanese steelmakers was half of that. The considerable iron ore overhang situation evident through 1977 was rapidly changing, and the world could face an iron ore shortfall by the mid-1980s