Solvay Essential Chemicals, North America, processes 4.8 million tons per year (t/y) of trona to produce 3 million t/y of soda ash at its Green River facility (above).

By Steve Fiscor, Editor-in-Chief

Developing and cross-training the next generation of miners and plant workers is a vitally important aspect of sustaining the mining business. Workers not only need to know job-specific skills, they also need to be prepared to meet the safety challenges often encountered in the mining business. Solvay Essential Chemicals, North America, developed a program for cross-training employees at its Green River facility, but safety performance lagged expectations and they knew they could do better. Working together, the company developed a safety program based on field level risk assessment that has had a profound impact on the facility’s overall safety performance.

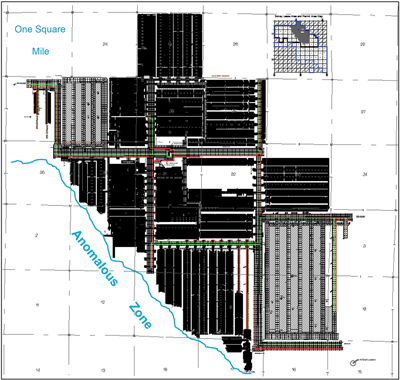

The Green River facility in southwest Wyoming refines trona to produce soda ash. The plant produces approximately 4.8 million tons of soda ash and derivatives. The company mines trona three ways: longwall mining, borer miners and solution mining. The orebody is bound to the southwest by a structure they refer to as the anomalous zone. The longwall mining method was selected to control stability with safety and rock mechanics in mind. In 1995, the mine experienced one of the largest known underground collapses, when a 1-sq-mile roof fall created a major seismic event.

Mining soft rock with a longwall is rather uncommon and so is the company’s approach to its operating strategy. The mine offers any individual the opportunity to reach the highest pay grade in as little as five years by cross-training over several job classifications. This approach allows the mine to operate lean and transition employees when and where they are needed. It exposes miners to several different aspects of the operation.

A little more than eight years ago, Solvay’s Green River mine experienced an increase in the frequency of accidents. “We were experiencing injuries at an unacceptable rate,” said Rowdy Heiser, manager health/safety for Solvay Green River. “We had three major amputations in 2009 that changed people’s lives forever. We had several near misses. Just 2 or 3 in. one way or the other could have been fatal events.” Anger took over. Management was not aligned and they defaulted to past practices of blaming individuals.

After some reflection, they took a step back and began to search for new tools and methods to improve safety performance. The management team brought company leaders together, asked for their input and offered their support. This transformational move created a level of trust among the workers. It also created a culture of safety based on three areas: risk assessment, safety interactions and hazard correction.

Solvay’s Green River facility has since demonstrated a dramatic improvement in safety performance. Leaders are not only leading, they are safety leaders. “Coming together as a group of managers was a major part of our success,” said Joe Vendetti, manager mining operations for Solvay Green River. “Most operations have good tools. How well those tools are used is the key.”

MINING TRONA

Of the 460 employees at the Green River facility, 190 of them work underground. This year, they expect to produce 4.8 million t/y of trona and they eventually hope to grow that figure to 5 million t/y. The shearer on the longwall cuts trona from a panel that measures 8,750 ft long, 625 ft wide and 10.5 ft high. The longwall represents about 55% of the total production.

The Green River mine also uses seven boring machines to develop future longwall panels, the mains and panels for tailings disposal (solution mining). Shuttle cars and one continuous haulage system haul ore from the borer miners to the mine’s network of conveyors.

The grade of the trona yields a 93% recovery rate. The tailings, the remaining 7%, are stowed underground. Trona is a soluble mineral. Tailings are placed in chevron panels and the liquid that decants from that process is also recovered.

The Green River mine has a current life of up to 70 years within the ore bed it is mining today. There are multiple beds so the operation could one day become a multiple seam mine.

The mine’s operating strategy was designed to develop employees with a diverse set of skills. Pay grades range from G1 (inexperienced) through G5 (fully competent). “Our pay system supports this as well,” Vendetti said. “We are one of the few mines where all employees in the mine have the ability to achieve the highest pay grade. A completely inexperienced new hire can attain the highest pay grade in as little as five years. To become one of the highest paid employees, they must be trained to a G5 level within their department and the G3 level in all other departments.” The three departments include mine production, mine utility/tailings and mine maintenance.

Of the 190 miners, only 18 are assigned to the longwall. As an example, four crews on a 12-hour rotation operate the longwall. The crew consists of a foreman and three operators. In addition to monitoring the headgate (the longwall’s central control system), they operate the shearer, pull shields and push the panline. Two mechanics overlap two of the crews. They perform inspections and write preventive work orders. “One day each week, a highly trained maintenance crew that may have worked in a borer panel the previous day will team up with the production people and they will perform all work orders and preventive maintenance,” Vendetti said. “Breakdown maintenance is performed by the miners on the face who are cross-trained to do this type of work. The management framework is such that production personnel must know about maintenance and vice versa. It is no different for the utility personnel.” If a longwall miner is on vacation, a utility person can operate the longwall.

THE CASE FOR CHANGE

Green River has a dynamic workforce of skilled professionals who are committed to what they do, explained Heiser. “When you think about the mine’s operating strategy, the initial questions are: How do you train and educate?” he said. “You can’t write enough procedures nor would you want to. You have to create a mindset where people understand risk. It’s not easy.”

A plan view of the mine shows the layout of the longwall panels.

A plan view of the mine shows the layout of the longwall panels.Working in an underground environment, miners constantly encounter safety rules and regulations as well as company policies. “Our people understood safety,” Heiser said. “They understood what it meant to them and the importance of it. Our workforce was committed and competent, but confused, and we lacked their trust.” He explained that miners need a level of trust that enables them to communicate freely and tell management things that are often unpopular.

The Green River mine was experiencing injuries at an unacceptable rate. “We did not know how to manage safety effectively in the field,” Heiser said. “We became frustrated and reactionary and we were not aligned.”

How do you manage risk to an acceptable level in a dynamic environment? What does that mean? Working with supervisors, management started developing tools, such as field level risk assessment, that added value. “It was a challenge,” Heiser said. “We told people we wanted them to do a risk assessment. And the response was: we do that all the time, otherwise we wouldn’t be here.” At what level and depth should they approach risk assessment?

For the program to succeed, they needed to shift the mindset of the workforce. They needed to create a culture where the workforce actively participated and embraced safety methodologies. “We needed to get people excited about safety,” Heiser said. “It’s OK to talk about safety. It wasn’t seen as something that was cool.” And, they had to get the management team aligned with the program.

To align the management team, they had to let go of traditional beliefs and approaches. “The first thing we had to realize is that we could not fix the problem alone,” Heiser said. “These people on the management team are good at fixing things, but we needed help to fix this problem.”

Managers and leaders had to become predictable. “People had to have a level of trust and understanding that, when something went wrong, they would know how we were going to react,” Heiser said. “We had to react in a way that embraced the information and the incident. As tough as it is, we had to overlook who caused it, and focus on how and why it occurred.” The group had to learn from mistakes rather than punishing those who made them.

The object was to move from simply following rules to using the tools. The field level risk assessment started that transformation, Heiser explained. He refers to the accident triangle and said that three things are needed for an accident: a person, equipment (or machinery) and energy. “When someone has been hurt at a facility, a person was interacting with machinery and there was some sort of energy released, i.e., a chain broke, a hydraulic hose ruptured, the roof collapsed, etc.,” Heiser said. “Field level risk assessment for us is that simple. We are focused on eliminating one of the legs of that triangle.”

Looking at all three legs, Heiser explained that management could chase people and equipment and they probably should. He also believes in investing in people, knowing that each person has an inherent risk profile that is different from everyone else. Equipment and machinery will experience failures and the mine has preventive maintenance programs in place. Energy is the one area where Heiser said the mine places an emphasis, and talks with people extensively.

Identifying all of the sources of energy in a mine would be difficult. When the energy is released, ask a miner where they will be positioned. “Once we created a dialogue of this manner, people could relate,” Heiser said. “When you can identify the issue, you can control it. Or you can at least manage it to an acceptable risk level. There are jobs we have to perform in the red zone. That’s the way it is. When you’re in the red zone, you had better be dialed in. You better know the source of the energy. When you are pulling a leg cylinder on the longwall, you need to assume that that chain or cable will break. What will the consequences be when the chain breaks?”

Miners could identify with consequences and probability. Once they understand the consequences, Heiser explained, they can place enough barriers between them and the energy to reduce the probability. “Field level risk assessment started the process of shifting the mindset and we began to think and see risk differently,” Heiser said.

SHIFTING THE MINDSET

The next step was recognizing that the supervisors were not the problem, they were the solution. As managers they owned it, but they were not going to fix it on their own. Of the total workforce of 465 on site (surface and underground), there are about 100 people who actively impact other people: engineers, planners, supervisors, foremen, contractors, etc. “We brought them together in one room and the management team explained that they had a case for change,” Heiser said. “People are getting hurt and it is frustrating. We know that you are frustrated too. We are not going to tell you what to do. We are going to ask you what we should do collectively.” They coined the group, “the Club.”

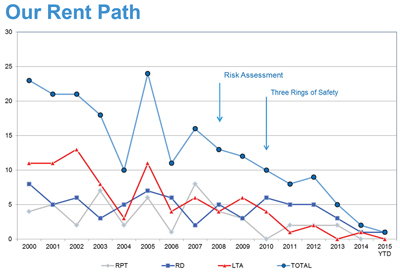

Figure 1—Green River’s history of reportable injuries spiked in 2005 and has declined since then.

Figure 1—Green River’s history of reportable injuries spiked in 2005 and has declined since then.Members of the Club set the standards and provided guidance and support. “When a decision is made at 2 a.m. and something unexpected occurs; if that person is using the three rings (risk assessment, safety interactions and hazard correction), we have their back. If they are not using those tools, they are on an island,” Heiser said. “The culture started to change and leaders started leading. We talked about what it means to be an effective safety leader. When a foremen tells you an effective safety leader does this, they leave the meeting with confidence.”

The Club concept was a catalyst in developing and shaping the safety culture and workforce. “Now we have leaders leading and the workforce noticing that they are serious,” Heiser said. “We have the right tools to assess risk. It was a platform for us to manage risk to an acceptable level. The leaders knew what we were asking of them and they had clear expectations.”

As the program advanced, the Three Rings of Safety evolved. A simple set of tools assists performance. As an example, a safety interaction is just that. The leaders asked management for the tools to have an interaction with their people in a positive manner and reinforce the positive things they were seeing. “During a Club meeting, one of the production supervisors said, ‘The miners on my crew are wondering why we are not doing safety interactions.’ That was the day I was waiting for. We introduced it to the workforce,” Heiser said. “Now, we conduct about 1,400 safety interactions per month. I’m not saying they are all quality. We do not track it. It’s an engagement tool with which people see value.”

This led to the creation of a culture where the management team could see people actively participating in safety. “They were engaged and it enhanced our ability to further develop and mature,” Heiser said. “It’s no longer difficult to review lock-out/tag-out policies, confined space, working at heights, critical risk procedures, safety management systems, OSHA 18001, etc. We are doing things today in safety that we never thought we would be able to do.”

To personify the transformation, Heiser refers to a field level risk assessment and a related near-miss report. Heiser tracks near misses as key performance indicators related to safety performance. “A supervisor and his crew performed a field level risk assessment on a job they were assigned. They were removing 4-in. pipe and they had discussed as a crew the steps in the process, as far as how they would manage the risk and implement the controls. They talked about a post-job review, minute by minute as they were doing the job as far as what was changing and what were they inducing into the process,” Heiser said. At the end of the job, the crew experienced a near miss. He filed a near-miss report.

A near-miss report is a chance to share and educate. Heiser uses this as an example because the supervisor was one who did not originally believe in the process. He did not see the value, but he had patience and he now sees the value to himself and others. “We have a culture today that is engaged as far as safety,” Heiser said. “The tools that we have in place do not have to be continually maintained or promoted because people see the value in it.”

Heiser suggested that management teams should find a place for basic field level risk assessment tools in their organizations. He also emphasizes the alignment of key players in the organization. “Without it, we would not have been able to progress,” Heiser said. “We did not have to like each other, but we had to work with each other and we had to understand each other.”

He also stressed that managers need to let go of traditional approaches and mentalities. “We had incidents that occurred during this process and it would have been easy to revert,” Heiser said. “Define your approach and stay committed. We started eight years ago. We haven’t changed. Our workforce doesn’t have to worry about what the next safety program will be.”

THE RESPONSE

Figure 1 shows Green River’s history of reportable injuries from the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration split into the three categories: reportable, restricted duty and lost time. “We were not very proud of the period from 2000 to 2008,” said Vendetti. “We implemented the risk assessment program in 2008. Safety is not a mystery. We all have common strategies. We all share a common objective. We have many common strategies, but we go about it differently. In 2006–2008, and as recent as 2010, even after the Club started, whenever something happened, everyone became angry. That does not improve safety performance.”

“When we asked the leaders in the company for their help, we started by asking them what does a safety leader look like?,” Vendetti said. “We asked the miners: Why do people get hurt? Lack of training? Wrong tool for the job? Mind or eyes not on task? Fatigue? You start listing those things.”

Solvay’s Green River longwall cuts trona from a 10- to 12-ft-high bed.

Solvay’s Green River longwall cuts trona from a 10- to 12-ft-high bed.The management group today tells the leaders that, if they are doing work in the best interest of the organization and they make a mistake, you’ll have our support, but you have to use the tools. “As time progressed, we told them we wanted a conscious effort and we started to get it,” Vendetti said. “Oftentimes, they would ask if it had to be a formal risk assessment. No, it didn’t. You could perform a field level risk assessment without the paperwork, but please just do it.”

As the company improved, the stats started to support the trend and they started driving minute-by-minute risk assessments, Vendetti explained. “You have to be on your game all of the time,” he said. “We knew we had something when we were talking in an awareness meeting with the entire rotation and the workforce said it really needed to be second-by-second.”

Vendetti has 36 years in the mining business (16 in safety and 20 in operations). As recently as five years ago, he didn’t believe the Green River operation could achieve the performance it did in 2014. “Today, I think that zero is possible,” Vendetti said. “We have a challenging industry and there are no guarantees.”

Risk assessment provided the platform to manage risk to acceptable levels. Leaders were actively involved and engaged with clear expectations. The Three Rings of Safety provided supervisors with the tools to lead. The Three Rings of Safety also provided employees with tools to actively embrace safety. This led to the creation of a culture where one could visibly see people actively participating in safety programs. It also enhanced management’s ability to further develop additional safety processes. According to Vendetti and Heiser, “Today, our entire workforce are safety leaders. Every employee is a member of the Club.”

This article was adapted from a presentation that Rowdy Heiser and Joe Vendetti gave at Longwall USA 2015, which took place during June in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The presentation and MP3 can be accessed at www.longwallusa.com.