Strong metals-market prices and rising demand often mask operational inefficiencies during super-cycle years. Mired in the current post-boom slump, producers are taking a closer look at cost-effective strategies to prepare for the next upturn.

By Russell A. Carter, Managing Editor

In-the-field retrofits of newer technology on vital production equipment can significantly extend unit service life, reduce energy consumption and improve overall productivity.

The global mining boom that pushed mineral production to record levels and drew upward of $74 billion of new project investment money into the project pipeline as recently as 2011 is officially over. Overall, mining project investment is estimated to have grown by 274% between 2002 and 2012, but once the downturn began, the falloff was steep: Our annual project survey, published in January, noted that only 95 new projects, with a total projected cost of $38 billion, entered the pipeline in 2013. This compares with 113 projects (valued at $47 billion) in 2012 and the peak year of 2010, when 167 projects worth $115 billion were reported.

As always, however, metals prices eventually softened and prospects for ongoing high profit margins in many metals segments have melted like ice cubes on a hot sidewalk. In response, industry focus has mostly switched from growth at any cost to identifying how best to survive weak market conditions and prepare for the next supercycle.

Several recent studies suggest that mining management should focus on higher productivity as the linchpin of any ongoing effort to pull corporate financial results away the from red ink zones.

And, several recent press announcements by leading international producers suggest that top executives—perhaps shaken by the events of 2013, during which literally dozens of CEOs were replaced, mostly due to shareholder unhappiness—are following that advice.

THE WAY IT WAS

As mining equipment steadily gets larger, faster and generally more efficient, it can be somewhat difficult for casual observers to understand why the industry even has a productivity problem—but there was a significant falloff in overall efficiency over the boom decade. For example, a paper presented at the 2013 Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration’s Annual Meeting by Richard Adsero and Graham Lumley—then of GBI Mining Intelligence, which was acquired by PwC in September 2013—pointed out that mining equipment productivity worldwide had declined significantly, based on their examination of data collected over the last 20 years. For surface mining equipment, their results indicated that median output for electric rope shovels was down 41% since 2003; hydraulic excavators, down 39% since 2008; front end loaders dropped 39% since 2007; and trucks fell 41% since 2006.

Clearly, the authors stated, the boom wasn’t good for industry productivity. They attributed the decline to three boom-related factors:

- The pressure to increase output during boom periods leads to increased “mining intensity”—higher levels of activity within existing mine sites, often involving new equipment, higher production targets and inexperienced operators, a combination that doesn’t often generate good results. “When the mine’s primary strategy is to shift as much commodity as possible, the easiest response is to simply get more equipment, not to make the existing equipment move more.”

- The industry’s recurring attitude that “this boom is different. It won’t end nearly as soon as the last one,” leading to complacency and a lack of emphasis on human- and equipment-asset productivity.

- A trend for new operations to deliberately acquire excess capacity, beyond the level of that needed to meet budgeted production. “There is a pervading attitude in terms of accessing capital of “make hay while the sun shines” because later in the mine’s life the availability of capital may not be as high.”

The industry’s productivity slump has been addressed by other studies, as well; one conducted by Ernst & Young (E&Y) in cooperation with the Sustainable Minerals Institute of the University of Queensland and Imperial College London, titled Productivity in Mining: Now Comes the Hard Part, cites four areas—problems with labor, capital expenditures, ore quality and managerial fascination with “economies of scale”—as key factors in declining productivity. The main points:

- Worker recruitment skyrocketed during the boom, but so did labor costs, and selection/training standards suffered. “From our interviews,” the E&Y study authors commented, “it became apparent that during the boom time many mining companies undertook less rigorous induction programs in order to get new joiners operational faster.” In addition, “During the commodity boom, the sector experienced high labor turnover due to increased bargaining power and availability of opportunities with higher wages and better conditions in other sectors.”

- Capital productivity was impacted by long lead times between investment and production and over-investment in capital. High employee turnover levels and an inexperienced workforce have had an adverse impact on equipment utilization levels.

- Depleting reserves and falling grades are contributing factors, with productivity falling per ton of ore mined.

- The authors noted that many mining executives observed a decline in productivity levels as their operations expanded, primarily due to the challenge of “managing complexity,” compounded by talent scarcity and lack of appropriate skills development.

The study goes on to say that a decade of higher prices concealed the impact of falling productivity. But when commodity prices finally softened, productivity improvement swiftly rose to second place in E&Y’s assessment of top issues facing the industry. “The supercycle [had] altered the DNA of mining companies to adapt the processes, performance measures and culture solely toward growth.”

DELAYING THE REACTION

As demand for mineral commodities rocketed upward during the boom, operating costs followed close behind—but high prices often can compensate for, or mask, rising expenses and inefficiencies. The industry’s traditional response to the end of a boom cycle has been reactive, across-the-board cost-cutting. This time around, it appears that producers are taking a closer look at what can be done, in cost-cutting efforts and other corporate strategies, to leave them in better position for a future upswing in market conditions. Indications are that they are at least considering the link between today’s cost reductions and tomorrow’s productivity rates.

In an industry report titled Tracking the Trends 2014: The top 10 issues mining companies will face in the coming year, U.K.-based consulting company Deloitte noted that mining companies have retrained their focus on capital prudence, cost discipline, portfolio simplification and non-core asset divestment in an effort to improve ROI. They are, said the Deloitte study, “shrinking the talent pool, reducing executive compensation and limiting funding approvals to only the highest quality projects in mining-friendly geographies.”

“The trouble with reactive cost cutting,” the study continues, “is that it is rarely sufficient or sustainable. Companies that slash the workforce now may find themselves scrambling to recruit new teams as the market recovers. Other cost cutting measures—from reducing travel to tightening cash management—tend to creep back up to historical spend rates over time and many companies get caught in a continuous cycle of cost takeout and cost creep.”

Yet another E&Y mining productivity study, titled Productivity in Mining: A Case for Broad Transformation, concurs; many organizations see productivity as a phase after the slash-and-burn of cost reduction and before the return to growth.

“When the focus on productivity is short term and/or temporary,” the study declares, “it is unlikely that improvements will be sustainable. The quest needs to be long term and requires a change in culture across the organization from the boardroom to the pit. This may require significant adjustments including:

- Changing mine plans,

- Reassessing mining methods,

- Making changes to equipment fleet and configuration,

- Reducing production, and

- Increasing or reducing automation.

Most of these areas have been untouched by cost reduction exercises, the study authors concluded. But recent company announcements provide glimpses into what some of the major producers are thinking about—and doing—to streamline and integrate company policies and systems to ensure improved future productivity in many areas. One of the prime areas for this focus has been in iron-ore production, where the Big Three—BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto and Vale—have invested billions of dollars in sunk infrastructure and equipment costs over the past several years.

Rio Tinto, for example, has indicated that it won’t cut its planned $8 billion capital spending figure for 2015, even in the face of slumping iron ore prices that have fallen to a five-year low mark. The company pointed to its $20.40/mt production costs as justification for its confident stance, with CEO Sam Walsh quoted as saying, “I don’t think I’ll be losing sleep about our iron ore business.”

But, largely behind the scenes, the company is doing all it can to cut costs and improve productivity, with measures extending from high-tech solutions such as operating the world’s largest autonomous haulage fleet spread across three of its Australian mine operations, to saving millions on equipment—up to 60% on underground roof supports for its coal operations, newly sourced from Chinese suppliers, for example. Also mentioned in its 2014 half-year cost-savings case study report are record productivity levels achieved at its Kennecott copper smelter operation in Utah, USA, where it recorded a record 189 metric tons produced per employee during May. Over the last two years, it has reduced production costs at the smelter by one-third.

At its iron ore operations in Western Australia, the company reported that it had, over the course of a year, increased its employees’ productive time by a cumulative 255,000 hours per year by shifting its training to “engage its people in a more efficient way.” In addition to ‘training smarter,’ it said it had streamlined systems and processes through standardization, and had eliminated levels of complexity from its employee assessment methods. On an individual, trickle-down basis, this and other measures resulted in 20–30 hours saved per year for a heavy equipment operator, for example, and about 25 hours per year for a mobile equipment maintainer.

The search for improved efficiency has filtered all the way down to employee recruitment. In an example provided by HireVue, a U.S. company specializing in video interview procedures and technology, Rio Tinto sought a way to interview candidates from around North America and the Pacific Rim in a cost efficient, more effective manner. Traditionally, recruiting and interviewing candidates consisted of an in-person interview following a resume screen. This had proven difficult to organize due to conflicting schedules of both hiring managers and candidates.

The company was spending an average of $800 per domestic candidate and $2,500 per international candidate for travel and hotel costs to bring candidates in for an interview. Results from the interviews in many cases were mediocre and the interviews were considered wasted time by hiring managers. In addition, the interview process usually lasted 60 days or more because of schedule conflicts in organizing initial interviews.

Using a combination of HireVue off-site and on-site video interviews, Rio Tinto was able to interview candidates locally and from around North America and the Pacific Rim within a matter of days. Each candidate interview was stored in a “talent” database and accessible by the company at a later date in case a new position was opened that better fit the candidate.

According to HireVue, this improved the hiring process immediately by making it more efficient and beneficial for managers to participate in interviews. They reported more success in the first face-to-face interview, since hiring managers already had a feel for the candidates’ personality and both candidates and managers were more invested in the hiring process.

The information that was collected in the HireVue video interviews included detailed written responses, evaluations and ratings by hiring managers. Rio Tinto managers were able to evaluate candidates from either the many locations that the company had operations in, or where the hiring manager was traveling. HireVue delivered the interviews from around North America at a cost savings of 77.2% compared with the cost of bringing in candidates to company locations for first round interviews. Time-to-presentation was reduced by more than 50%.

A HARD LOOK AT LABOR

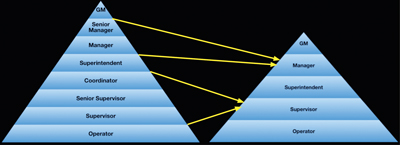

BHP Billiton, the world’s largest mining company and arch-rival to Rio Tinto’s iron ore business, is leaning heavily on internal systems streamlining and enhancement along with data analytics to boost its overall productivity. A recent company presentation by Mike Henry, president—HSE, marketing and technology, indicated that streamlining extends all the way down to paperwork, for example: in a graph showing the number of planning policy pages and required approvals generated between 2008 and 2014, the page count dropped by roughly 90% and approvals by about 60%. The operational structure also has been simplified, as shown in the accompanying diagram.

Henry said labor represented 41% of group operating cost base in fiscal year 2014—but improvements enabled a reduction in total labor spend of 10% in FY14 while increasing “people productivity” 38% since FY12 through strategic insourcing to achieve a “fit for purpose” employee-to-contractor ratio.

He also said the company anticipates a continued increase in people productivity by:

- Supporting its people in developing their capability,

- Utilization of technology to automate and simplify labor-intensive operations, and

- Focusing workers on the highest value adding activities.

It’s also targeting better productivity from its equipment assets, reporting a 6% increase in total asset utilization that underpinned a 9% increase in group production in FY14. This was achieved, according to the company, by benchmarking the performance of its equipment internally and externally, along with other measures, and resulted in trucking fleet performance during FY14 that included 3% better availability, 10% higher utilization and a 10% increase in haulage rates, enabling the fleet to move 22% more tons.

Overall, BHP Billiton reported productivity-led volume and cost efficiencies of US$2.9 billion achieved in FY14, exceeding its target by 61%, as part of more than $6.6 billion of sustainable productivity gains embedded since FY12.

BHP Billiton restructured its management hierarchy for improved efficiency, moving from a multilayered organization in 2010 (left) to its current simplified structure (right).

BHP Billiton restructured its management hierarchy for improved efficiency, moving from a multilayered organization in 2010 (left) to its current simplified structure (right).SMART, CONNECTED—AND PRODUCTIVE

From these announcements, it appears that the major producers are measuring what must be measured, changing what must be changed and relying strongly on technology to help them meet future productivity targets. Industry suppliers are paving the way for progress in this latter area by focusing on system connectivity—from mine face to mine office, as well as to the corner office and even to the factory.

Although examples of this trend abound, a recent article in the Harvard Business Review illustrated as well as any the current picture. In writing Strategic Choices in Building the Smart, Connected Mine, authors Michael Porter, Eric Snow and Kathleen Mitford trace how Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA-based Joy Global, since the late 1990s, has focused on building smarter, connected products to help optimize performance at entire surface and underground mining operations, as measured in cost per ton of ore produced per day.

The effort began in 1998 when Joy began offering a remote-controllable continuous miner, followed by the ability to allow a service tech to plug into the machines and download sensor and fault data. The trend continued; in 2001, machines could be connected by armored data cables to computers on the surface, and in 2008 Joy introduced a wireless communications system that allowed collection of information from several mine control rooms. Joy’s latest automated longwall systems now use about 7,000 sensors to monitor and control system performance, passing information from one component to another and to the surface.

Today, after refining its technology and establishing nine Smart Service Centers in seven countries, its customers worldwide can electronically access the company’s resources and expertise, while employing its equipment control system technology to deliver data in real time from surface and underground operations to the centers.

As the HBR article pointed out, Joy Global, like many other suppliers, gradually changed its business model from just selling equipment, to selling products and services. The introduction of its smart, connected products now allows it to provide a wider range of services, including the capability to work efficiently with customers to identify, analyze and reduce production bottlenecks in the mine.

And, like many other forward-looking suppliers, Joy Global is using its communications, control, data gathering and analysis capabilities as a foundation from which to consider other business models, based on performance guarantees or selling product-as-a-service. In addition, it’s looking at new types of equipment that could provide customers with lower cost of operation or higher performance, such as a hybrid shovel/excavator, transformational technologies applied to its LHD line and high-performance longwall systems for low-seam coal mining. New systems will work hand-in-hand with Joy Global’s recently announced decision to employ IBM’s Big Data and Analytics technology, which offers advanced predictive analytics solutions for more productive performance (see p. 100).