Tailings are filtered and stacked at Newmont’s Eleonore mine in Canada.

As a founding member of ICMM, the world’s leading gold producer shares its experience developing procedures to manage its tailings storage facilities

By Steve Fiscor, Editor-in-Chief

The mining industry’s response to recent tailings dam failures as far as guidelines and educational resources has been impressive. The International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) was one of the first organizations to react and E&MJ has documented those efforts. Also, the Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration (SME) quickly established a leadership role in providing resources to the engineers who are designing and operating tailings storage facilities (TSFs). In a span of five years, the mining industry worked together to break down previously siloed information and make it accessible to everyone.

The new standards, guidelines, timelines and regulations along with the transparency and the flood of information can be overwhelming at times. Now that countries, states and provinces are demanding accountability from operators and responsibility from the Engineers of Record (EOR), mining professionals designing tailings dams and implementing these procedures to safely design, construct, operate and close them are expecting more scrutiny. They will need to provide transparency to regain the public’s trust.

At the 2021 MINExpo INTERNATIONAL trade show, which was held September 13-15 in Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, Kim Morrison, senior director for global tailings management for Newmont, provided extensive insight into the company’s tailings management program. She is responsible for all the TSFs at Newmont’s global operations and the company’s legacy sites. Her responsibilities include reviewing and developing standards and guidelines, overseeing governance programs, providing peer reviews, and overseeing training and development programs. Outside of Newmont, Morrison actively works to raise the awareness of the importance of tailings management. She serves as the founding chair for SME’s Tailings & Mine Waste Committee and she is editing SME’s Tailings Management Handbook—A Lifecycle Approach, which has more than 100 authors and is scheduled to be published in early 2022.

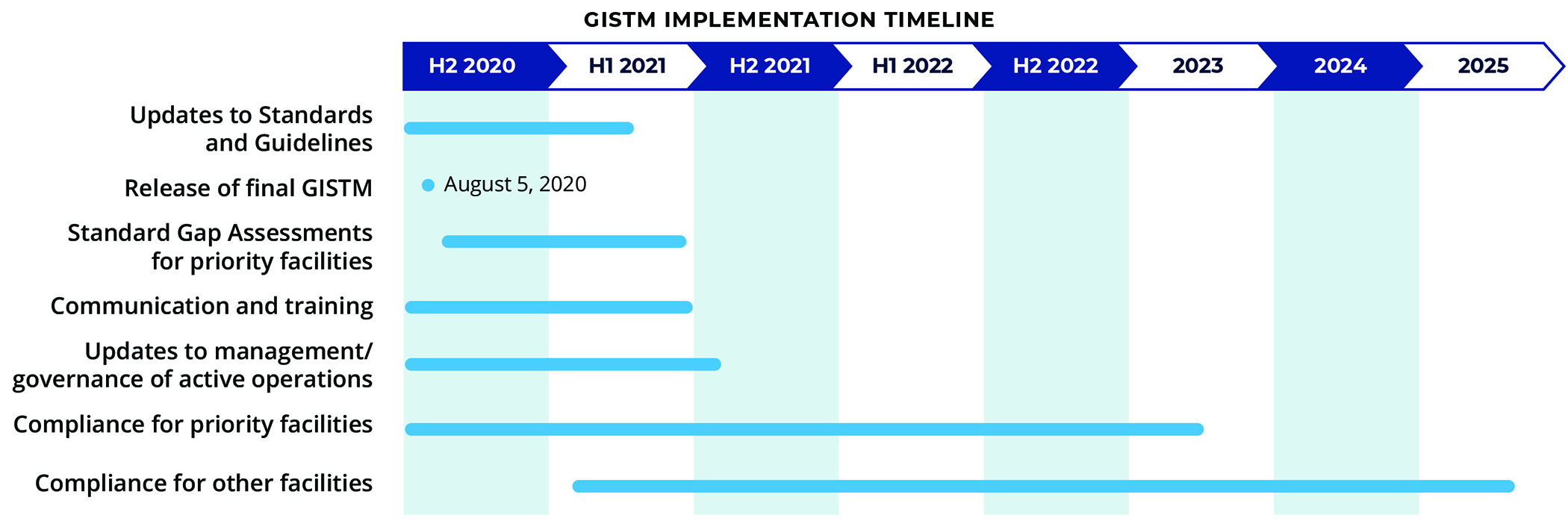

Newmont’s proposed five-year program to ensure all of its TSFs are aligned with the GISTM.

In her presentation, Implementation of the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management — An Owner’s Perspective, she explained how the GISTM came about and provided details about Newmont’s programs. As an ICMM founding member, Newmont committed to implementing the GISTM, put forward by the council. She and her team, working closely with Newmont’s site, regional and corporate cross-functional teams, are now more than one year into the five-year program to ensure all of Newmont’s TSFs are aligned with the GISTM.

How Did the GISTM Come About?

“The GISTM is about society’s trust or the lack thereof with the mining industry,” Morrison said.

Since 1960, on average, 2.5 tailings dams have failed per year. Three recent failures brought considerable harm and broke the public’s trust of mining companies ability to build and safely operate TSFs. The first was the dam failure at Imperial Metals’ Mount Polley mine in British Columbia on August 4, 2014. “[This incident] was dubbed the largest environmental disaster in Canada’s history,” Morrison said. “It resulted in significant changes to the regulatory environment in British Columbia as well as changes to guidelines in North America, specifically around roles and responsibilities.”

In the four years leading up to the Mount Polley TSF failure, there were five EORs from three different consulting firms associated with the TSF. This ultimately led to a review of the EOR principle, Morrison explained. As a result, Morrison led a U.S.-based taskforce on behalf of the Geoprofessional Business Association (GBA) that culminated in the development of Proposed Best Practices for the Engineer of Record for TSFs.

A little more than a year later (November 5, 2015), the Fundão tailings dam at the Samarco iron ore mine in Minas Gerais, Brazil, failed. Referred to locally as the Mariana mine disaster, an orange surge of sludge wiped out homes and villages along the Doce River, killed 19 people, and eventually reached and polluted the Atlantic Ocean. Reinforcing a recurring theme, Morrison said it was dubbed Brazil’s largest environmental disaster. The Samarco joint venture partners (BHP and Vale) were members of the ICMM. In December 2016, the ICMM published their Position Statement on Preventing Catastrophic Failure of Tailings Storage Facilities.

In Ghana, the Akyem mine’s TSF employs two cells.

A little more than three years later (January 25, 2019), again in Minas Gerais, Brazil, Dam 1 at Vale’s Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine failed killing 270 people. Known as the Brumadinho dam disaster, it was dubbed the worst industrial accident in Brazil’s history. “Major modifications were made to the regulations in Brazil after Samarco, but it took 18 months for those regulations to take effect,” Morrison said. “After Córrego, the regulations changed overnight due to the lack of trust with the mining industry. Within days, the state of Minas Gerais banned upstream construction of tailings dams and they required de-classification of other upstream constructed facilities in addition to many other things.”

These failures sparked outrage around the world and it affected Morrison personally. Six days prior to the failure, she was on a hillside overlooking the Córrego dam. It failed during her flight home. When she landed, her phone was blowing up with messages and voicemails from her friends and colleagues in Brazil. It also took her career in a different direction. Newmont decided they wanted to strengthen their approach to tailings management and Morrison joined them in April 2019.

The GISTM

Shortly after the Brumadinho dam disaster, the ICMM, the UN Environment Program and the Principles for Responsible Investment co-convened a global tailings review in an effort to improve safety and establish best practices for TSFs. The key outcome was the GISTM.

The GISTM aims to prevent catastrophic failures of TSF by providing operators with specified measures and approaches throughout the TSF’s life cycle, taking into account multiple stakeholder perspectives. Published August 5, 2020, all ICMM member companies committed to implement it for their priority facilities within three years and all facilities within five years. In addition to the standard, the ICMM’s Tailings Working Group recently (May 2021) published the Tailings Management: Good Practice Guide, and separate Conformance Protocols to support implementation. These documents are available on the ICMM website (www.ICMM.com).

The GISTM is divided into six topic areas, which encompass 15 Principles and 77 auditable requirements. It defines a TSF as any facility that has been designed to manage or contain tailings that has a height of 2.5 m or more and a combined water/solids volume of 30,000 m3. “It applies to all TSFs, whether they are legacy, closed, operating as well as TSFs just being conceived,” Morrison said. “It doesn’t apply to any facility that has been considered safely closed. The definition of ‘safely closed,’ however, is a bit ambiguous and we at Newmont are developing guidance as to what safe closure means to us.”

Newmont’s inventory of TSFs includes 21 active, 37 in-active and 32 that are reclaimed/closed.

Newmont’s Implementation Journey

Newmont is the largest gold producer with nine world-class assets. The company is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year, and became a founding member of the ICMM in 2001. In 2004, the company established a Safety & Sustainability Board Committee to provide oversight, advice and counsel on key issues, including tailings management. “Later that year, Newmont published its first sustainability report, demonstrating commitment to transparency,” Morrison said. “Last year [2020], the company expressed its commitment to the GISTM and we are now on our implementation journey.”

As a member of ICMM, Newmont has committed to a five-year schedule, Morrison explained. “Specifically, we are targeting compliance for our priority facilities, which includes our active operational facilities and other TSFs with very high or extreme consequence classification by August 2023,” she said. “We’re already more than a year into that timeline. For the remaining TSFs, we expect full conformance by August 2025.”

Newmont’s inventory of TSFs includes 21 active, 37 inactive and 32 that are reclaimed/closed. Of the 90 total, a fraction (14%) is considered a priority in accordance with the ICMM definition, Morrison said. “To meet the full set of requirements of the GISTM, we revised our global TSF and heap-leach facility environmental management standard and we introduced a new TSF technical and operations standard in 2020 that address the many technical and governance aspects of tailings management,” she said. “We also revised and published our sustainability and stakeholder engagement policy. We have a myriad of new guidance documents to support implementation. We have developed guidance documents for each of the new standards; dam breaches, inundation, mapping and emergency response; as well as guidance on risk management.”

In late 2020, Newmont also published a tailings management governance framework that aligns with the GISTM and details the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities for tailings management within Newmont. Morrison said it uses four lines of defense (LoD):

• First LoD — Site-based implementation with a Responsible Tailings Facility Engineer or Person (RTFE/P) and a dedicated EOR;

• Second LoD — Systematic third-party reviews with independent tailings review boards (ITRBs) and periodic dam safety reviews;

• Third LoD — Our accountable executive and corporate-based support; and

• Fourth LoD — Executive leadership team and board of directors that accepts overall accountability.

Newmont’s TSF management governance framework has four lines of defense.

“We have identified and named RTFEs or RTFPs for all active operations and select legacy sites,” Morrison said. “We also confirmed terms of references were in place for each of our EORs, confirming official appointment of that role. We also have ITRBs in place for most of our active operations and select legacy sites, and we’re in the process of implementing additional ITRBs for the other sites.” Dean Gehring, executive vice president and chief technology officer, was named Newmont’s accountable executive last year. The corporate tailings and dams team, which Morrison leads, has delegated responsibilities of the accountable executive.

Newmont’s global risk management system requires that all segments of the business use a common risk assessment framework based on international standards to identify, execute and manage business risk, Morrison explained. “This six-step framework helps make informed decisions on risks that directly impact our business. We recognize that a catastrophic failure with any of the TSFs is a significant risk to our business. We perform risk assessments on a site-specific basis considering all phases of the TSF life cycle. As a project matures, the level of detail of the risk assessment must also evolve.”

Earlier this year, Newmont published a tailings risk assessment guidance document and Morrison said they have been busy implementing that. “We have been performing Level 1 potential problem analyses and Level 2 failure modes and effects analyses at all active operations and we plan to extend the risk assessment to legacy sites next year,” Morrison said.

To mitigate the risks inherent in the design, construction, operation and closure of TSFs, Newmont also developed a critical control reporting process. Critical controls, Morrison explained, are the controls most effective at preventing or mitigating the consequences of the most significant risks. Within TSFs, it reports on four critical controls:

1.) Monitoring instrumentation against established thresholds or triggers;

2.) Monitoring reclaim pond levels against operational criteria;

3.) Conducting independent reviews and implementing those recommendations; and

4.) Implementing change management requirements.

“In 2020, we performed a landscape review of our existing TSF’s geotechnical monitoring practices as well as an external landscape review of real-time monitoring platforms,” Morison said. “We are currently deploying a real-time enterprise approach to monitoring all of our TSFs at our operating sites to improve our visibility and performance.”

Morrison believes that transparently reporting performance helps build trust with Newmont’s stakeholders by holding itself accountable for results and acknowledging areas for improvement. “Integrity is a core value for Newmont,” Morrison said. “We believe it’s extremely important to provide disclosures that summarize the positive as well as the negative impacts of the TSF management system Newmont has in place.”

The GISTM requires that Newmont regularly publish updates on its commitment to safe TSF management. This includes information on the status of the implementation of the tailings governance framework, an organization-wide policy on standards and approaches to design, construction, monitoring and closure of TSFs. Newmont has published that information at https://newmont.com/sustainability/environmental-responsibility/tailings-management/default.aspx.

It publishes an annual Sustainability Report that includes a tailings section.

“As we work to address Principle 15 of the GISTM, we are working to enhance our disclosures and provide more information,” Morrison said. “We are providing updates to our inventory disclosure biannually.”

As an ICMM member company, Newmont committed to implementing the GISTM. “We embrace it as it raises the bar for integrated social, environmental, economic, and technical considerations, elevates accountability, and strengthens oversight and governance,” Morrison said. “We encourage a broad uptake of the GISTM for all mining companies that build TSFs.”

6 GISTM Topic Areas

Topic Area I focuses on project-affected people. To respect human rights, including the individual and collective rights of indigenous and tribal peoples, a human rights due diligence process is required to identify and address those that are most at risk from a tailings facility or its potential failure. To demonstrate respect, project-affected people must be afforded opportunities for meaningful engagement in decisions that affect them. The requirements within Topic Area I are intended to be cross-cutting in terms of being addressed across all operational activities and ongoing throughout the tailings facility lifecycle.

Topic Area II requires operators to develop knowledge about the social, environmental and local economic context of a proposed or existing tailings facility, and as part of this, to conduct a detailed site characterization. It asks for a multidisciplinary knowledge base to be developed and used by the operator and key stakeholders in an iterative way to enable all parties to make informed decisions throughout the tailings facility lifecycle. These decisions will arise in the context of the alternatives analyses, the choice of technologies and facility designs, emergency response plans, and closure and post-closure plans, among others.

Topic Area III aims to lift the performance bar for designing, constructing, operating, maintaining, monitoring and closing tailings facilities. Operators are asked to demonstrate the ability to upgrade a facility at a later stage to a higher consequence classification. For existing facilities, where upgrading is not feasible, the operator must reduce the consequences of a potential failure. Recognizing that tailings facilities are dynamic engineered structures, Topic Area III requires the ongoing use of an updated knowledge base, consideration of alternative tailings technologies, the use of robust designs and well-managed construction and operation processes to minimize the risk of failure. A comprehensive monitoring system must support the full implementation of the observational method and a performance-based approach must be taken for the design, construction and operation of tailings facilities.

Topic Area IV focuses on the ongoing management and governance of a tailings facility. It provides for the designation and assignment of responsibility to key roles in tailings facility management, including an accountable executive, an engineer of record (EOR) and a responsible tailings facility engineer (RTFE). Further, it sets standards for critical systems and processes, such as the Tailings Management System and independent reviews, which are essential to upholding the integrity of a tailings facility throughout its lifecycle. Cross-functional collaboration and the development of a learning organizational culture that welcomes the identification of problems and protects whistle-blowers are also included.

Topic Area V covers emergency preparedness and response in the event of a tailings facility failure. Operators must avoid complacency about the demands that would be placed on them in the event of a catastrophic failure. The standard requires operators to consider their own capacity in conjunction with that of other parties, and to plan ahead, build capacity and work collaboratively with other parties, in particular communities, to prepare for the unlikely case of a failure. Topic Area V also outlines the fundamental obligations of the operator in the long-term recovery of affected communities in the event of a catastrophic failure.

Topic Area VI requires public disclosure of information about tailings facilities to support public accountability, while protecting operators from the need to disclose confidential commercial or financial information. The standard concludes by requiring that operators commit to transparency, and participate in global initiatives to create standardized, independent, industry-wide and publicly accessible information about tailings facilities.