The company’s strategy is to rebuild and prepare for better times

By Gavin du Venage, South African Editor

Many expected platinum miner Lonmin to slip quietly into the night—its assets broken up and sold off—but the century-old company is not done yet as it commences the fight for its life.

Many expected platinum miner Lonmin to slip quietly into the night—its assets broken up and sold off—but the century-old company is not done yet as it commences the fight for its life.

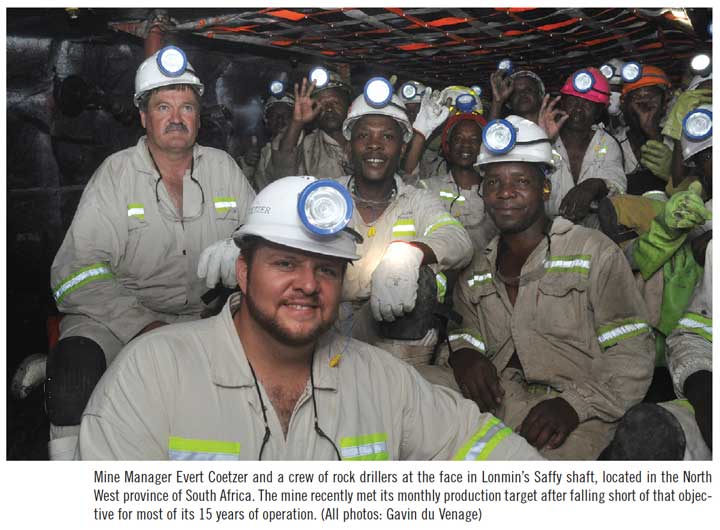

A sign that the South African platinum producer’s wide turnaround strategy may succeed is the ebullient mood at its Saffy shaft, which lies at the heart of the platinum belt in the country’s North West province. E&MJ was invited to tour the facility.

Ever since its inception in 2000, Saffy has been the troubled child of the group, consistently failing to meet production targets. Designed to produce 200,000 metric tons (mt) of ore a month, for much of the 15 years of its life, it has produced a little more than half that. Now, this past November, Saffy delivered 204,000 mt, up from barely 130,000 tons in November 2014.

“It’s a great moment for all of us—the workers and management. We are very excited about this achievement and what it means for the company,” said Rodney Opperman, general manager at Saffy Shaft, as senior staff filed around a table in the Saffy briefing room to be told the news. “If we can reposition Saffy, we can reposition Lonmin itself.”

For management, workers and long-suffering shareholders, achieving the production target is a huge step forward. For labor, it means retained jobs and performance bonuses and, for Lonmin’s stockholders, the promise of some day seeing that return in value is more than an illusion.

“We had a hard look at our business plan and saw we were not opening up our ore reserves,” said Opperman. “Over the past year, we’ve worked on this and now the stoping crews can move about freely.”

The workforce, too, played its part: “The maturity of the crews is making itself felt as these teams have been together for as long as two years.”

Opperman added that Saffy had achieved this while maintaining an excellent safety record. “Productivity without safety is not worth counting,” he said.

Good news has been scarce for Lonmin and the 35,000 men and women in its employ. The past few years, it has survived in the shadow of what has become known as the “Marikana Massacre” after panicked police officers gunned down a charge of striking mine workers, killing 34 in front of television cameras.

In the 24 months since, Lonmin has also endured an industry-wide strike that shut down production for half a year—all against a backdrop of a declining platinum price as international demand crumbled on the back of a softer global economy.

The world’s third largest producer of platinum, Lonmin is a resource institution. It was founded in 1909 in order to acquire mining rights in Northern and Southern Rhodesia, now Zambia and Zimbabwe, and for the next century continued to build its mining presence in the region.

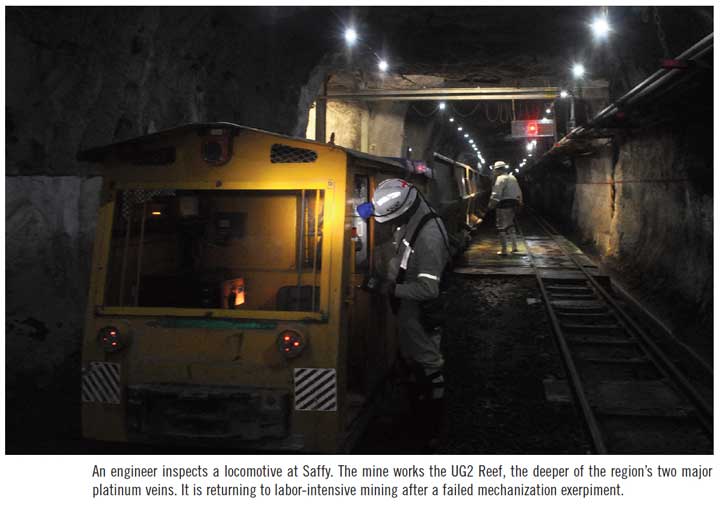

The events of the past few years, however, threatened to end its existence, coming at a time when larger rivals are selling off assets and reducing the number of mines they operate. Lonmin has also paid a heavy price for its fateful decision in 2004 to embark on a mechanization program. The results were financially disastrous.

“One of the problems with mechanization here at Saffy is the high angle of the dip and the narrow width of the orebody,” said Evert Coetzer, mine manager at Saffy. “When the orebody is narrow, it means more rock has to be removed to get at it. We have a dip angle of about 10°–12°, which makes it difficult for an articulated vehicle to navigate. They depend on the angle being close to flat.”

In 2008, the decision was made to begin phasing out mechanization and to return to conventional methods: rock drill crews working at the face.

“We are thankful for the people who took the decision to return to conventional mining,” Coetzer said. “It couldn’t have been easy.”

Mechanization is something of a holy grail for the South African mining industry, which remains one of the most labor intensive in the world. Labor accounts for more than half of the operating expenses on most shafts, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers.

More workers also means more injuries and fatalities, especially as mines go deeper. However, although there’s a wealth of expertise and original equipment to draw on, full mechanization remains elusive. “I don’t believe there’s the kind of technology out there that’s suitable for the orebody that we mine on the Western Limb of the Bushveld Complex,” said Mike da Costa, executive vice president–business support at Lonmin. “Either we will have to use smaller machines than currently available or open the width of cut and take the dilution.”

Others are likely to continue the drive to replace men with machines. Rivals Anglo American and Impala Platinum have test programs running. Robert Friedland, the Canadian mogul developing the Platreef platinum project, has repeatedly said the operation will be fully mechanized.

For now, though, Lonmin will focus on traditional muscle-powered operations. More than 800 m underground, the signs of the transition are evident. Battery-powered locomotives hum on tracks hauling ore, and the machine-gun thump of rock drills can be heard. Of the fleet haulers, dumpers and dozers that once worked this mine, there’s no sign.

“These are tough crews, and we’ve worked hard at putting the right guys together with the right supervisors,” Coetzer noted. The mood of resentment and anger that emerged from the period of strike unrest has disappeared. Everyone just wants to get on with the job.

Coetzer himself, along with many of Saffy’s senior staff, is a recent appointment, brought in earlier this year. More than anything, clearing the air and opening up communication between labor, supervisors and management have been driven home over the past year.

“I know it sounds trite, but getting everyone to talk to each other and understand where the other guy is coming from has turned things around for us,” said Mike Kevane, one of Saffy’s two rock engineers.

The relative youth of platinum mines means that they are shallower than the more venerable gold producers, which operate at depths of up to 4 km underground. They are also free from the Swiss cheese of abandoned shafts and tunnels that bedevil gold mining operations, where illegal miners can hide undetected for weeks on end.

Instead, the approaches are free of muck and crumbling rock, at some stages so clean that it appears closer to a modern underground railway station rather than a working mine.

At the face however, it’s still raw mining. Saffy is working the UG2 reef—the deeper of the two major platinum veins. The other, the Merensky reef, is closer to the surface and generally richer. On this particular property, however, UG2 is the better prospect.

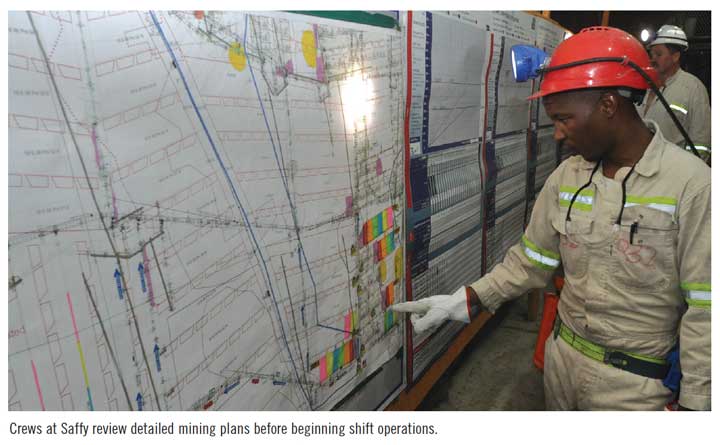

Crews operate in a space as narrow as a kitchen table. Rock drills hammer in holes for charges, in a set pattern determined by the rock engineer. Blasting takes place early evening and, two hours later, the night shift arrives to begin cleaning and removing the ore.

Coetzer pointed to the stacks of concrete bags that form the pillars supporting the rock. Each stack is capable of holding up 200 tons. “In every part of the operation, we are looking to improve safety and save costs. Eventually these stacks will be replaced by these,” he said, pointing to steel props being used closer to the face.

Called “sticks” by the miners, the props are easier to use, quicker to put in place and, in the long run, cheaper than concrete. It will be one of many incremental changes brought in as part of a relentless pursuit to bring down costs while focusing on zero harm at every stage.

Little talking is done as the rock drills beat out the sound of hell itself. When instructions must be passed, it’s usually in Fanagalo, the Esperanto of the mines. A hodgepodge of ethnic tongues, such as Zulu, Xhosa, Tswana, Shangaan and others, it also includes some Afrikaans and a smattering of English.

From time to time, the unions try and get Fanagalo banned. The language is a throwback to the apartheid era, and incorporates little of the niceties of the tongues from which it borrows. There’s no please or thank you; rather, it’s a “do-this, do-that, yes sir” kind of thing.

It persists, because Fanagalo is quick to learn and communication is vital when working under more than a million tons of rock.

Above ground, a different kind of communication is also taking place. As part of its turnaround strategy, the company will shed 6,000 jobs or about 17% of its workforce. Recalling that Lonmin has experienced severe periods of labor unrest, and job cuts are a red line with unions, the decision had to be handled with care.

“It has been a challenging three years,” said Executive Vice President–Human Resources at Lonmin Abey Kgotle. “Coming from the tragedy of 2012, and building a relationship with a new union, then going into a five-month strike, has made for a difficult time.”

For much of the past two decades, Lonmin, along with its peers, has been dealing with the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). For years, the NUM was the voice of workers across the sector, but this began to change a few years ago as a rival emerged. The Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) began life as a breakaway faction of the NUM but has since become a standalone force with which to be reckoned.

From a management perspective, a new union has meant dealing with an entirely different labor structure. Broaching job cuts had to be handled with the utmost care.

“The fact that we reached agreement on a restructuring process suggests that the relationship with AMCU is maturing,” Kgotle said. “It has been a tough process and hard decisions needed to be made. But we are finding each other.”

The sting of job cuts has been softened by using natural attrition and voluntary severance packages. Others are being retrained and moved to vacant posts. “We’ve already reached 60% of our headcount reduction target; quite remarkable in five months.”

The softly-softly approach appears to be working. “Our engagements with AMCU are robust and they are not afraid to challenge us,” Kgotle added.

For the men in suits, hard work also lies ahead. In November, Lonmin reported an operating loss of $207 million. To repair the balance sheet it will cut platinum output from more than 750,000 oz currently to 700,000 oz in 2016, and then down to 650,000 oz for 2017 and 2018.

The company said it would write down the value of its assets by more than half by taking an impairment of as much as $2.05 billion. Lonmin also turned to shareholders to raise almost $400 million through a rights issue, drastically diluting its holdings.

According to Bloomberg, shareholders agreed to buy 19.2 billion new shares, and HSBC Holdings, JPMorgan Cazenove and Standard Bank Group’s South African unit will procure subscribers for the remaining 7.8 billion by mid-December. The banks would also pick up unsubscribed shares.

The value of the stock, which climbed to $13 billion at its peak in 2007, is now just $210 million, a spectacular destruction of wealth for its shareholders.

“We’ve taken extensive time to put together a plan, which was then again extensively reviewed by external parties. The general agreement is that it is a robust plan to suit a low-priced platinum environment.”

Still being considered are shaft closures. The W1, E1 and 1B shafts are coming to the end of their lives, and will likely be closed. It’s quite possible, though, that operations will continue—contractors working the shafts have approached Lonmin with plans to prolong mine life.

At Hossy shaft, development work has already stopped and, over the next 18 months, remaining work will be completed when it will be put on care and maintenance. Newman shaft is closing but could also be revived in a better price environment, particularly as it can be used to access a nearby undeveloped orebody.

At the same time, it is unlikely that Lonmin would become a takeover target, given the overall market conditions for platinum. Both Anglo Platinum and Impala Platinum have begun shedding assets. However, this is not a route Lonmin is considering.

For now, the company’s strategy will be to rebuild and prepare for better times ahead.

Da Costa noted that the next three to four years would see a guarded price outlook as years of over-investment by the industry weigh on a recovery. However, the situation should begin to improve after that as demand begins to outstrip supply.

Platinum remains an industrial metal used in vehicle catalytic converters and emerging fuel cell applications. It also enjoys growing share of precious metal sales, particularly in the Far East.

“Any investor in the company now has a positive outlook for platinum—they believe in the future of the metal. The fundamentals look good. So our immediate focus is to get the fundamentals of the business right over the coming period. When price improves—and it will—we’ll be ready.”