Removing the mask from fatigue leads to a cultural shift in openness

Fatigue technologies tend to come in three flavors: roster optimization, screening technology and real-time monitoring. Roster optimization technologies identify whether a roster is good or bad and whether an individual can participate in overtime shifts. Some are more advanced with wearable technologies to determine whether a person is fit to work. Screening technologies assess an individual’s fitness for work at a single point in time. Some are validated scientifically while others fit more into the toy spectrum. They serve the same purpose nonetheless. The real-time operating monitoring space has two categories: wearables and driver-facing cameras.

A little more than 10 years ago, there were 81 fatigue technologies on the market. Four of those had a strong industry uptake and the rest were very much in the toy category. Today, that figure has been reduced to 36 commercial fatigue-monitoring technologies. The same four technologies represent most of the market share. And, 32 of them still overwhelmingly fit in the toy category. “The term toy category could be considered a demeaning term, but these technologies are either so scientifically flawed that there is no way to validate them or they sit at such an early stage of development they have seen no industry uptake,” said Dan Bongers, chief technology officer, SmartCap.

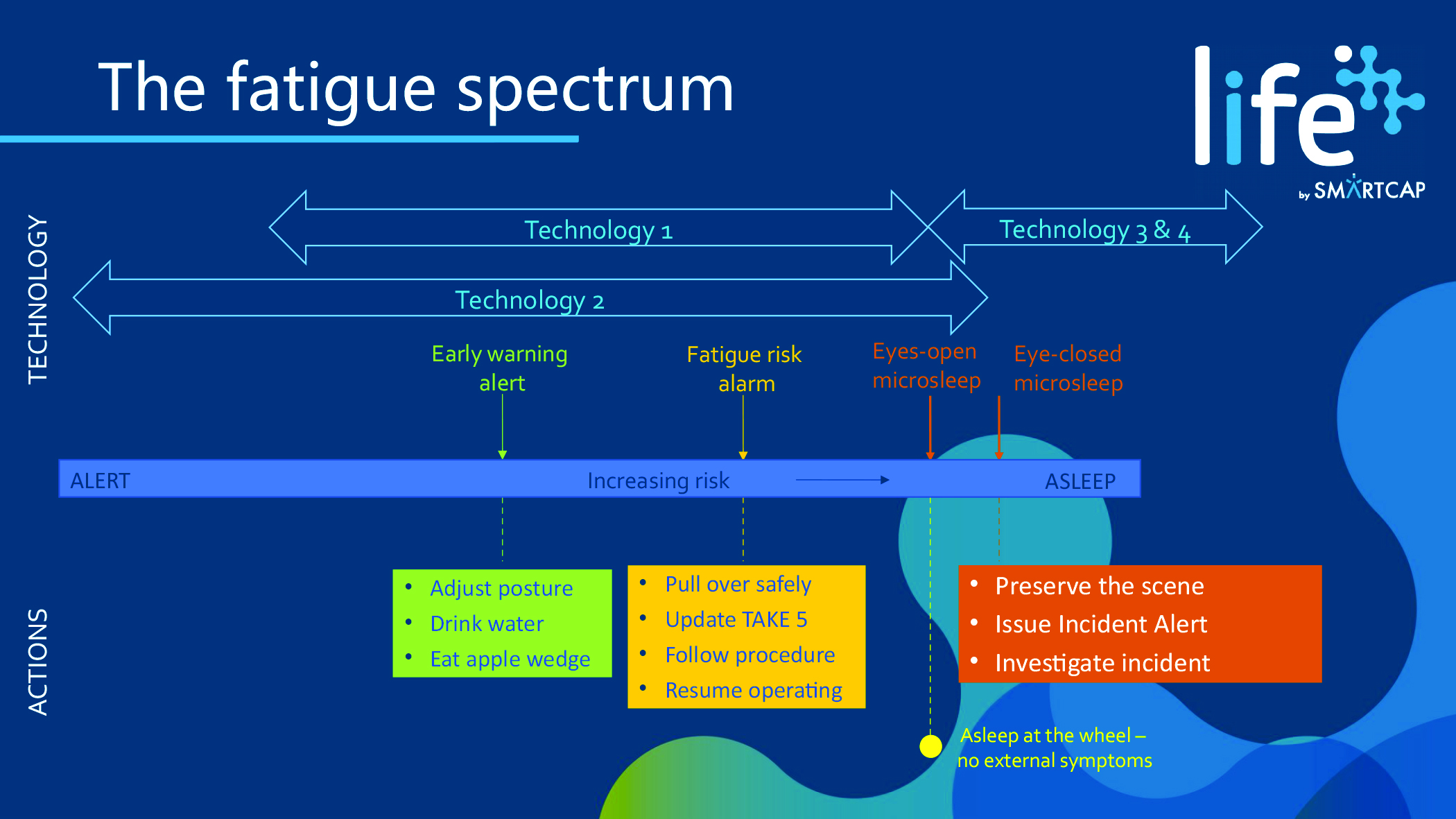

Each of the established technologies fit well into the fatigue spectrum, which spans from bouncing-off-the-walls highly alert to clinically asleep. What we have been taught to fear the most is the eyes-closed microsleep, which is characterized by eyes unintentionally shutting, chin falling toward the chest and then jerking back. “This is the characteristic symbol of fatigue,” Bongers said. “What is not well-known is that 100% of the time before a behavioral microsleep, a non-behavioral microsleep occurs. This is when a person is actually asleep with no visible external symptoms.”

Moving across the fatigue spectrum, one can see the actions that need to be taken in response to the information provided, which becomes more and more severe. For the technologies on the more alert side, where individuals are showing symptoms, but they are not yet asleep, actions might include adjusting posture (sitting up straighter), drinking some water or eating some fruit. As the operator progresses more toward the right where the technology identifies genuine fatigue risk, those actions become more significant, Bongers explained. “An operator might pull over and take five or the company may have put procedures in place to help the operator get through the rest of the shift safely,” Bongers said. “At the extreme, where an individual may literally be asleep, the actions will be much more severe.” Depending on the business, this might be considered an incident or a near miss.

The four highly adopted technologies today fit into four different parts of the fatigue spectrum. Technologies three and four are different brands essentially doing the same thing. This difference in the actions that someone can take and the difference in what the technology can do is key.

What to Expect

What Bongers has learned over the last 10 years is that selling and implementing fatigue technology is not as easy as it should be. He pointed to five challenges that seem somewhat unique to fatigue technology.

Challenge No. 1: Fatigue Technology is Perceived as New

This is unfortunately fueled by the fact that the validation or the science behind them in many cases is self-declared, meaning the people who are vouching for it either own or are strongly affiliated with it. Generally, the industry uptake is low (less than 3% market penetration). A mine looking to implement these tools has difficulty identifying a similar site that has validated the technology. They are not new. They just feel new because the industry adoption rates are so low.

Challenge No. 2: The Assessment

A mining operation considering fatigue technologies will want to test them on a small-scale trial or pilot. Those are two completely different terms, Bongers explained. “A trial tests the technology,” Bongers said. “Does it accurately measure fatigue? Does it detect sleep? A pilot test on the other hand assesses whether the technology fits with the business. Will the operators accept it? When it provides information, does it allow managers time to intervene in a manner that suits the company?

“It’s very difficult to place sensible acceptance criteria on these small-scale tests,” Bongers said. “For the most part, they are very subjective. Testing is more well-suited for a lab rather than a mine. To avoid miners feeling like guinea pigs, they should be told, ‘This is a proven technology and we are working with it to see if it fits our business.’”

Throughout the assessment process, Bongers emphasized that mine operators should do their homework. “There is a wealth of information out there,” Bongers said. “Having done this in 31 countries, I believe there is always a way to satisfy the validity or rule out a technology based on a desktop study. There is no need to place the technology in an operation to see if it’s the real deal. For that reason, I encourage companies to do pilot tests rather than trials.”

Challenge No. 3: Operator Acceptance

The goals for the pilot test should be communicated clearly. Fatigue technologies are monitoring an employee’s behavior. So, there is always a Big Brother worry associated with implementation. Contractors have a different mindset than employees, Bongers explained. “They feel like they have no voice and they will be viewed as undesirable if they speak up and have no chance a full-time employment,” Bongers said.

During implementation, operators almost always voice highly inflated or imaginary concerns. These mask the real concerns, Bongers explained. “When it comes to wearables, they will say they are worried Bluetooth will give them cancer despite the fact that they own a cell phone and a tablet and drive an automobile with Bluetooth.”

Rumors spread that a certain number of fatigue alarms will lead to termination. “After speaking with countless executives, we found that couldn’t be farther from the truth,” Bongers said. “These systems were never intended to be used as a disciplinary tool.”

A lot of these issues can be solved with engagement and the key is to do it before the technology is introduced. Early communication is critical. Privacy should also be considered before implementation. “If the controls and the policies as to how the information will be handled are presented early, a mine can get ahead of a lot of these adoption concerns,” Bongers said.

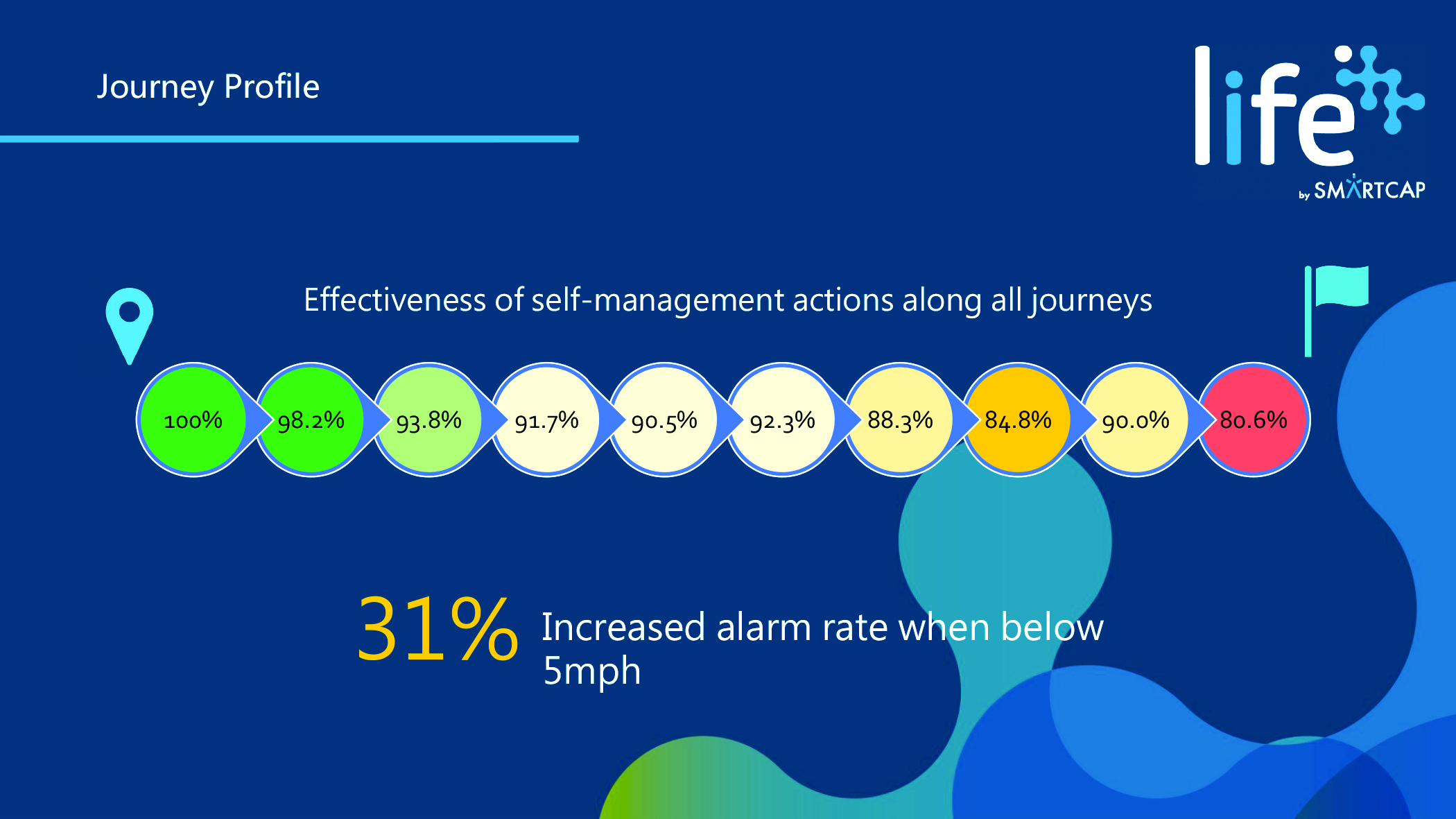

Toward the end of a shift, the effectiveness of self-management actions declines from 100% to 80.6%.

Challenge No. 4: Return on Investment

Good fatigue-detection technologies are not cheap, but they are not really expensive either. The mining business is reluctant to talk about money at the same time it talks about safety, so it’s difficult to isolate the impact of a particular initiative. Miners could learn from over-the-road truckers. In that business, margins are razor thin and they are constantly justifying investments. Rather than only looking at the safety benefits, maybe miners could also consider gains such as the reduced wear and tear on the machinery and productivity improvements.

Challenge No. 5: Policies & Procedures

Mine management should take an open approach with the workforce about policy and procedures during implementation. They should explain how the data will be collected and used to reinforce policies and procedures. The mine’s workforce is a smart group of people and they already suspect it’s being done.

Management should never treat technology as a silver bullet. Buying and implementing a system will never automatically improve safety performance. If it fits into a comprehensive safety program, it will complement it.

When implementing a technology, it’s crucial that its use aligns with the policies in place, Bongers explained. As an example, if prior to the technology arriving, the company considered an unintended sleep as a high-risk potential incident or near miss, then introducing a detection technology should carry the same weight. “Just because its data on a graph in the dispatch area doesn’t mean we have changed the definition of an incident on site,” Bongers said. “If someone were to detect a microsleep with new technology and not react as they would the day before, then we have a relaxation of the definition of the incident.”

Similarly, consider an operator that has received an early warning: You’re heading the wrong direction! You’re at risk, but nothing has happened yet. If the mine management treats that differently than the operator’s same assessment, problems will likely ensue. “If the reaction moves from take a break and grab a cup of coffee to park the truck and complete a report, there is a dramatic difference in response,” Bongers said. Reaction and responses should remain consistent from before and after implementation.

Noticeable Trends

The results highlight what many already expected or knew. Humans are more fatigued during the nighttime hours. Bongers emphasized that fatigue alarms can happen at any time. “Another takeaway is that everyone has a unique fatigue profile,” Bongers said. “It’s highly repeatable and it’s easy to see these individuals. One operator may struggle with night shift. Another may be bad on day shift because of light sensitivity of which they are unaware.”

With early-warning technologies, measuring the effectiveness of actions that people can take in immediate response identifies positive results. During the first month, they are 88.8% effective in taking self-management actions. After two months, they were 90.8% effective. “Over two months, their effectiveness in responding improved,” Bongers said. “These individuals determine what works best for them to improve alertness, whether it’s eating some fruit or improving posture.”

When one looks at the effectiveness of the actions taken, the profile changes depending on how far they are into their shift or journey. Toward the end of the shift, the effectiveness of self-management actions declines “We have also found the queuing causes the response to early warning to decline more quickly and it has an echoing effect,” Bongers said. “If an operator has queued up anytime during the shift for the next two hours, their risk profile is significantly greater.”

If an individual progresses beyond the early warning to a fatigue alarm, something beeping or shouting to the point where they have to cancel an alarm, an immediate increase in alertness is seen, Bongers explained. “Once the technology is introduced, over the first three months, that response becomes more heightened because people discover what actions they can take that work better for them.”

When self-management actions from a warning alert are combined with the fatigue alarms and interventions, the mine will see a significant reduction in fatigue alarms during the first few months and even greater reduction in repeat alarms.

As far as individual profiles, when the system highlights an individual that is having difficulty, the company can step in to find a solution to help that operator. “What we always find is that operators aren’t the same,” Bongers said. “The overwhelming majority do not get fatigue alarms and a few represent most of the fatigue alarms. The overall stat is that 4% to 7% of any workforce represent 75% of all risk events. If a mine is discussing RoI, this is where it can realize the biggest bang for its buck. Managers can engage with operators in one-on-one conversations to find out what’s happening with them and how they can be helped. That will eliminate the majority of the risk.”

Among all of the cool benefits that come with the technology, what Bongers sees is a massive improvement in individuals willing to self-report fatigue. By removing the mask of fatigue and demystifying what it is and removing the stigma, Bongers explained, a cultural shift can be seen in people being more open about the risk it presents.

This article was adapted from a presentation Dan Bongers, chief technology officer with SmartCap, gave at Haulage & Loading 2019, which was held during March in Tucson, Arizona.