By Simon Walker, European Editor

Is Alberta ready for the next phase of oil sands development? E&MJ looks at the opportunities and challenges facing Canada’s energy export leader.

Caterpillar equipment at Imperial Oil and ExxonMobil Canada’s Kearl surface mine, where production began in April. (Photo courtesy of Imperial Oil)

Since the 1970s, Alberta has supplied a significant proportion of Canada’s hydrocarbon needs, producing a raft of petroleum products from the heavy crude oil and bitumen resources that underlie much of the north of the province. And, while the industry struggled for decades in the face of low international prices for oil produced from conventional sources, rising prices in the 1990s led to a string of new project proposals. Several have been implemented; more have been put on the back burner; and some have failed to materialize for either technical or financial constraints. Today, the oil sands industry produces around 1.7 million barrels per day (Mbbl/d) of synthetic crude oil (SCO) and diluted bitumen (dilbit), 1.4 Mbbl of which are exported via pipelines to refineries across the U.S.

With the exception of oil shales, the Athabasca basin oil sands represent a unique resource in terms of their extraction potential, in that a proportion—albeit a relatively small one—is amenable to surface mining. Industry sources estimate that only around 3% of the total 142,200-km2 resource area is covered by less than 75 m of overburden—the cut-off point between surface mining using shovel-and-truck operations, and in-situ production systems.

Clearly, the industry represents a major player in the North American energy market, both domestically and through its exports but, as has already been seen in relation to U.S. coal production, the amazingly rapid development of shale gas and “tight” oil over the past five or six years has transformed that market out of all recognition. And while official forecasts are predicting the oil sands industry will double its capacity by 2017, it is now facing a rather different energy scenario than was the case until very recently.

Add to that an upsurge in concerns over its impact on the fragile boreal environment, health issues and rapidly escalating construction costs for new projects, and it is equally clear to see that the industry will have to come to grips with a number of new challenges if it is to develop as has been expected. Carbon dioxide emissions have provided a further focus for development opposition, while in the U.S., the extension of the existing Keystone pipeline to supply oil sands-derived crude and dilbit to Gulf Coast refineries awaits government approval in the face of concerted opposition from the environmental lobby.

Resources and Production Systems

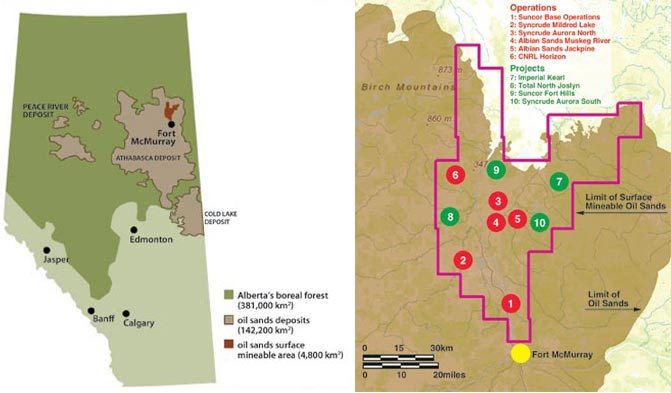

Alberta’s oil sands resources lie in three main areas: Athabasca, Peace River and Cold Lake, with the Athabasca deposits containing more than 80% of the 168-billion-barrel bitumen resource. Highly viscous, the bitumen represents the residual heavy hydrocarbon fraction of an original crude from which the lighter fractions have been lost through post-formation bacterial digestion. In total, the resource is the third-largest oil source in the world, after those held by Saudi Arabia and Venezuela, with oil sands bitumen representing 98% of Canada’s oil resources.

Large-diameter pipelines transport SCO and dilbit to U.S. refineries. (Photo courtesy of Enbridge)

Large-diameter pipelines transport SCO and dilbit to U.S. refineries. (Photo courtesy of Enbridge)

Nine mining projects are currently operating, being developed or approved, plus more than 50 thermal in-situ production facilities. Even more operations produce heavy crude that is sufficiently fluid not to require heating for in-situ recovery in conventional wells.

According to the U.S.-based energy consultancy, IHS CERA, mining currently accounts for slightly less than half of Alberta’s oil sands oil production, with in-situ thermal processes—steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) and cyclic steam stimulation (CSS)—supplying a further 40%. The remainder comes from operations that use the CHOPS (cold heavy oil production with sand) technique on less viscous heavy oil resources. In-situ systems in general overtook mining as the principal source for the first time in 2012, and will continue to increase in importance. SAGD has only become a mainstream technology since the early 2000s, and is projected to account for 45% of the total output by 2030.

Keystone XL

Operated by TransCanada Corp., the 36-in.-diameter Keystone pipeline carries synthetic crude and dilbit from Alberta to refineries in the U.S. Commissioned in 2010, the 3,460-km-long Phase 1 pipeline runs from Hardisty, Alberta, to Steele City, Nebraska, and then to Patoka, Illinois. Phase 2, opened the following year, extended the pipeline from Steele City to Cushing, Oklahoma, with work currently under way to complete Phase 3, the Gulf Coast pipeline. Commissioning is scheduled for later this year, providing access for Canadian synthetic crude to Nederland, Texas, and from there on to refineries in Houston.

Left: Alberta’s oil sands resource. Right: Current and approved surface mining projects. (Images courtesy of the Alberta government)

However, the Keystone project will remain incomplete until U.S. presidential approval is received for Phase 4, Keystone XL. Planned to run from Hardisty on a more direct route through southern Alberta, Montana, South Dakota and Nebraska to Steele City, this will increase capacity on the Keystone network by 830,000 bbl/d to 1.2 Mbbl/d. According to TransCanada, “The pipeline is a critical infrastructure project for the energy security of the United States and for strengthening the American economy.”

In addition to handling Canadian crude, Keystone XL will take oil from the newly developed Bakken Formation fields in Montana and North Dakota. TransCanada stated that the new pipeline will reduce U.S. dependence on imports from Venezuela and Saudi Arabia by some 40%.

Following rejection of its initial application in 2012, the company now anticipates receiving its permits later this year, with completion of the $5.3-billion project targeted for 2015. However, permitting is by no means a foregone conclusion, with President Obama having stated in his speech at Georgetown University in June: “The net effects of pipeline impact on our climate will be absolutely critical in determining if the project is allowed to go forward.” The U.S. Department of State has yet to reach its decision on Keystone XL, with presidential approval or rejection after that.

The project has brought a number of issues to the fore, including both the potential for environmental damage in the event of an oil spill, and the wider challenge of carbon emissions in relation to climate change. TransCanada’s case has not been helped by the rupture of an Enbridge pipeline carrying Canadian dilbit at Marshall, Michigan, in 2010, which released more than 830,000 U.S. gallons into the Kalamazoo River—and is likely to incur Enbridge at least US$1 billion in clean-up costs.

Slow Development, Huge Investment

In 2004, the industry was in the process of the first major expansion in terms of operators, with Shell’s Albian Sands project under construction. Up to then, Suncor and Syncrude had the oil patch to themselves, at least in terms of surface mining, although both had increased their own capacities several times during the 30 or so years since mining had started. In addition, Syncrude and Suncor had converted their operations from draglines and bucket-wheels to conventional shovel-and-truck, with Syncrude bringing in the world’s largest hydraulic excavators (O&K’s RH400—now renamed as the Caterpillar 6090 FS).

If the size of the operations was impressive, the costs involved in both expansions and new projects was eye-watering. At the time, Shell was budgeting C$5.2 billion to bring its mine and stand-alone upgrader on stream, with costs having increased from an initial C$4.1-billion estimate. Suncor had just spent C$3.4 billion on an expansion, C$1.4 billion more than anticipated, while the Syncrude 21 expansion program, then aiming to increase capacity to more than 500,000 bbl/d by 2015, carried a C$8-billion price tag.

As far as new projects were concerned, True North Energy was promoting Fort Hills, at an expected cost of C$3.5 billion, while Canadian Natural Resources was budgeting C$8 billion to bring its Horizon surface mining operation on stream in three stages. In the event, Canadian Natural commissioned the first phase at Horizon in 2009 at a cost of C$9.7 billion.

To put things into perspective, however, big budgets are nothing new to the Alberta oil sands industry. Indeed, the C$230 million Sun Oil spent to bring its “Great Canadian Oil Sands Project” into production in 1967 was at that time the largest single-project investment in Canadian industrial history.

Today, the industry is facing an uncomfortable period for decision-making. With project financing hard to source, increasing public concerns over CO2 emissions and the long-term impact of U.S. shale gas and tight oil developments still unclear in relation to the wider energy market, expansion and development projects involving surface mines are under review, and it would be a bold CEO to commit to spending such vast sums only to find that the market had shifted away from its presumed path.

Ten years ago, Suncor was talking about its Voyageur expansion project. In March, after a strategic and economic review, and with the plant part-built, Suncor announced that the project was canceled. “Since 2010, market conditions have changed significantly, challenging the economics of the Voyageur upgrader project,” said Steve Williams, Suncor’s president and CEO. “This decision is in line with our commitment to capital discipline and our stated plan to allocate capital with priority given to developing higher-return growth projects.”

With a capacity of 200,000 bbl/d and a C$11.6-billion price tag, the Voyageur upgader was planned to produce synthetic crude from the Fort Hills mine, with production beginning in 2016. However, Fort Hills remains on the drawing board, and the new plant joined a list of upgraders that had been proposed but then canceled over the past five or six years. One of the problems, at least as far as the Alberta producers are concerned, is that it is cheaper to install cokers (which help convert heavy crude into lighter oils) at existing U.S. refineries than it is to build new Canadian upgraders, where the economics are closely tied to the price differential between bitumen and light oil. As light oil prices in the U.S. market have fallen, the viability of upgrading bitumen in Alberta has become much less attractive.