Since time immemorial, mining finance has offered great opportunities for entrepreneurial inventiveness. In its early years, E&MJ built up an enviable reputation for trying to protect investors by identifying suspect stock flotations. A trawl through past editions highlights some of its successes—and the chicanery that led to them.

By Simon Walker, European Editor

Whether or not the journalist Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain), then Nevada-based, actually made the oft-quoted analogy attributed to him remains open to question. What is not, by contrast, is the reality that he used his position to help promote mining stocks at a time when the Comstock boom was at its height.

In his 2006 book, A Hole in the Ground With a Liar at the Top: Fraud and Deceit in the Golden Age of American Mining, author Dan Plazak noted that in 1863 Clemens was active in extolling the potential of the North Ophir mine. Using the age-old trick of having a property name similar to that of an already successful operation, in order to muddle potential investors, North Ophir was offered as a stock mine and was never going to make it in silver. Indeed, the native silver to be seen in the shaft was nothing more than melted-down half-dollars; unfortunately, the melting was not wholly successful, and it was noticed that some of the rich showings still bore traces of coinage inscriptions.

Still, that did not deter the speculators and mining promoters from plying their trade. According to Plazak, “About 400 Comstock mining corporations sold shares, but most of them owned no property of any value. Fraud was endemic to mining shares traded on the San Francisco exchanges.”

E&MJ was quick to make its point. The editorial in its edition of January 11, 1879, stated uncompromisingly: “The effects of this wild and speculative fever was the ruin of hundreds or thousands of those who indulged in its excesses, and it brought out again in clear relief the disreputable management, which has so long obtained in Comstock mines and which is a shame and a disgrace to San Francisco.”

But while the Comstock, with all its improprieties and skullduggery, provided a focus for both fortunes and the unfortunate for decades, the concept of promoting worthless prospects to unwary investors was nothing new. Far from it, and while it would take a lot of research to determine the first-ever recorded instance of short-changed investor ire, it is not hard to guess that the roots of the mining swindle run very deep indeed through ancient history.

Investment ‘Opportunities’

Investment ‘Opportunities’

Taking European mining as an example, current knowledge of the organizational structure of the industry is fairly sparse before, say, the 16th century. Even then, however, Agricola bemoaned some of the sharp practices employed by miners and mine-owners in the central European ore fields with which he was acquainted. “A prudent owner, before he buys shares, ought to go to the mine and carefully examine the nature of the vein lest fraudulent sellers of shares should deceive him.” Nothing new there, then.

It is reasonable to assume that at that time, investment in mines would have mainly been the responsibility of the owner of the mineral rights, be it an individual or an organization such as a university or an abbey. The mine owner could either put up the money himself or induce his associates to do so. That the consequences of a default might well have been physically unpleasant to the perpetrator, to say the least, it may well have been an incentive for financial probity.

And while mining share ownership did indeed spread more widely among those with sufficient spare cash, it was not until a greater proportion of the population—of the major towns and cities at least—began to have the opportunity to invest that the potential for financing swindles really started to gain some momentum. Rather than the close funding partnerships of the past, there was now a group of urban investors who in all probability knew next to nothing about mines located in the more remote parts of their country. Taking England as an example here, its main metal mining areas were on the periphery (Cornwall, Wales, the Pennines) while the new investor base in London and other cities was remote from the action, both geographically and technically.

One of the earliest recorded scams, and one that resulted in a parliamentary inquiry, involved an operation even further afield, in Ireland. In 1825, the Arigna coal and iron mines were sold to a group of investors, who then—as company directors—resold them to a newly floated company. Specific illustrations from the inquiry included: “The books of the Arigna Company contain many false entries;” “The prospectus of the Arigna Company was a delusion and a fraud on the public;” and “It is not the practice for the directors of joint-stock companies to sell shares belonging to proprietors without their authority.”

And so it went on. In A History of Tin Mining and Smelting in Cornwall, D. Bradford Barton noted that in 1881, the flotation of the Great Polgooth United mine was “largely a fraudulent criminal promotion that later achieved notoriety in the law and criminal courts.” Just two years later, the lawful shareholders in the Dolcoath mine—then the most important tin producer in the county—discovered that the mine clerk, John Mayne, had issued 203 forged shares over a four-year period, netting himself some £12,000. Mayne received seven years in prison, while the shareholders received a bill of nearly £800 for legal costs in his prosecution.

Inflated Assays Earn Swindler 6 Years

Falsifying gold assay results from the company’s Boka project in China earned Southwestern Resources Corp. former CEO John Patterson a six-year jail sentence in 2013. Between 2003 and 2007, Patterson, who admitted to securities fraud and illegal insider trading, issued 24 news releases about the project that contained inaccurate assay information.According to the British Columbia Securities Commission, “while some of the discrepancies were minor, in at least 60 instances, Southwestern had reported significant gold findings where the actual assay result was negligible.”Paterson also admitted to illegal insider trading in the settlement agreement. In July 2007, he sold 50,000 Southwestern shares with the knowledge that the company would have to issue a news release correcting the gold assay values for the Boka project. In doing so, he avoided a loss of more than C$150,000 as the company’s market value fell by C$157.7 million once the news became public, with total shareholder losses estimated at some C$260 million.In 2002, the company’s share price had risen from C$0.15 to more than C$40 on the back of the reported assay results, CBC noted in its report on Patterson’s trial.

Boom, Bust; Bubble, Bust

As well as being able to benefit from domestic opportunities, British investors soon had the country’s expanding empire in which to dabble. Indian gold shares were an early attraction, followed by Australia, South Africa and, of course, the Americas. Even without fraudulent promotions, success was by no means certain: The Company of Adventurers in the Mines of Real del Monte managed to lose £5 million between 1824 and the company’s collapse in 1849.

Mining capital flowed into South Africa somewhat later. In Gold Paved the Way, A.P. Cartwright provides an overview of the country’s first big gold rush in 1884—not to the Rand, but to the Barberton district in the northeast Transvaal: “…the men of Kimberley…had money to burn. They ‘rushed’ the new gold-field as nothing in South Africa had ever been rushed before. Thousands of claims were pegged, hundreds of companies were floated and an avalanche of shares printed.

“A stock exchange was established in the new town of Barberton, and investors in Britain fell over one another to buy shares, sold by the agents of the companies in London. They knew nothing about the geology of the Transvaal, or for that matter about the companies whose tastefully engraved share certificates they bought. The magic word was ‘Sheba.’ Any company that said its claims were on the ‘Sheba Reef’ sold its shares as fast as it could print them.

“Shares in the Sheba mine soared to £100 at the height of the boom, but when the truth came out the rest of the edifice collapsed even more quickly than it had been built. Hundreds of thousands of shares became completely valueless.

“Barberton was soon a name that stank in the nostrils of British investors. And the memory of Barberton made them cautious about shares in South Africa for years to come. The truth is that most of the Barberton companies were bare-faced swindles, advertised by prospectuses in which there was no word of truth.”

Then came the Rand, and by the mid-1890s, mine speculation and promotion was again in full swing. Money poured in, both from the newly prosperous locally and from Britain and France. In its edition of October 5, 1895, E&MJ’s editorial looked at the situation, and was clearly worried. “The fact that in London and on the Continental exchanges a very active speculation has been going on for a year or more past in the stocks of the South African gold mining companies is very generally known, but few of us have appreciated the great dimensions which that speculation has attained.

“Many experts were doubtful of its value in the beginning…When the facts were established, however, the movement of capital to the district began to assume extraordinary proportions.”

Then came the caution: “The first question that an investor would naturally ask is, what are the returns and profits obtained? We find from the records accessible that there are only about twenty-five Transvaal companies which are actually paying dividends on their stocks.”

The editorial went on to point out that there were another 131 companies listed in South Africa, mostly on the Rand, with capitalization of US$139 million and stock trading at a value of more than $566 million—none of which was paying a cent in dividends.

“There is a third class of companies whose stock is just now in great demand,” the editorial continued. “These are variously known as ‘trusts,’ ‘banks’ and ‘exploration companies,’ and they are organized primarily for the purpose of buying and holding stocks of actual mining companies.”

Penny Stock Scam Routed Through Offshore Accounts

At the end of 2014, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) charged two Canadian citizens with conducting an international microcap fraud scheme by stockpiling shares in a Tennessee-based coal mining company, Americas Energy Co., and funding a multimillion dollar promotional campaign to hype the stock, while simultaneously dumping their shares and routing the proceeds through offshore accounts. The SEC alleged that Bruce Strebinger and Brent Chapman had generated proceeds of more than $17 million through their elaborate scheme.

“Strebinger and Chapman rigged a penny stock in their favor while staging a massive promotional campaign,” said William P. Hicks, associate director for enforcement in the SEC’s Atlanta regional office, speaking at the time. “They disguised their scheme by dumping their shares in relatively small amounts over extended periods of time, and they attempted to hide their proceeds from U.S. regulators by routing them through offshore accounts.”

The scam involved a campaign to promote Americas Energy stock to prospective investors through blast emails and direct mailings of stock promotion reports that contained false and misleading statements, the SEC explained. In March, it ended up costing Strebinger a future bar on promoting penny stocks and an order for more than US$1.5 million in restitution. The SEC’s litigation against Chapman was still under way at that time.

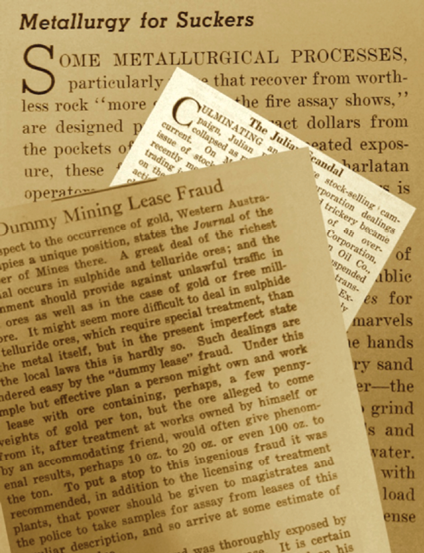

E&MJ Hoisted Red Flags

Established in New York but with its proprietor, Charles Western, having had first-hand experience of mining out West, it was not long before E&MJ was highlighting what its editors perceived as being risky investments. And the publication was not afraid to speak out in a manner that today would probably incur at the very least some legal correspondence.

Its edition of February 1, 1879, included its views on a recently received prospectus. “The prospectus of the Big Giant Silver Mining Company has, at least, the virtue of brevity,” the editorial ran. “The only other expert (?) testimony on which the simple-minded public are invited to hand over their money is the tolerably safe statement credited to “the French Mining Engineer Simones” (whoever he may be) that “the silver mines of Colorado give undoubted evidence of great wealth.”

“This ‘Chicago enterprise’ presents all the characteristic outcroppings of a well-defined ‘wild-cat’, and we cheerfully call attention (gratuitously) to the fact that, as it is now presented, it is an excellent enterprise to let alone.” E&MJ went on to list the names of the company officers, and asked its readers to provide further information about them.

In today’s celebrity culture, some companies find it beneficial for their perceived credibility to have recognized “names” at least as figureheads within their corporate hierarchy. So did the promoters of fraudulent mining stocks 140 years ago, with the names of the purportedly good and great sometimes appearing regularly as new flotations hit the markets.

In its front-page editorial on July 30, 1892, E&MJ flagged up one such person—the former Union army general and one-time senator Benjamin Butler who, it appeared, had a long-standing reputation for both self-aggrandizement and involvement in shady dealings. “It will be wise for investors to carefully avoid enterprises in which he is active,” the editors advised.

Their foreign correspondents were also keen to sound warnings, such as this one from London, dated September 28, 1895, just as the South African gold bubble was brewing nicely. “During the past week, two companies have been brought out with names calculated to seriously mislead the speculator. The Vincent Rhodesian syndicate is supposed to be Sir Edgar Vincent, of the Imperial Ottoman Bank, but it turns out to be an unknown quantity called James Vincent, whose name has been used by adroit promoters.”

Under the heading “The Prince of Mining Frauds,” E&MJ’s December 8, 1923, edition drew attention to the fact that 30 years on, nothing much had changed when it came to stock scams. “The prince of all the wildcats, promoted by the king of all the liars, would seem to be the Sitka Gold Mining Co., alias, it seems, the Pacific Gold Mines Co.” By way of justification for this very pointed accusation, E&MJ noted that the company claimed to have office addresses in New York, Cooper River (Alaska) and Reno (Nevada). “A visit to [the New York address] failed to reveal any trace of the company, which, moreover, is not listed in the New York telephone directory. As for Cooper River, the Geological Survey says that there is no such river,” the editorial stated.

And clearly the publication was not afraid of sailing very close to the wind indeed. Under the heading “The Ely Central Promotion,” its February 19, 1910, edition included the news that “We have been sued by B.H.Scheftels & Co., a corporation, for $750,000, and by B.H.Scheftels for $100,000. According to a statement in a daily newspaper,…these suits are brought on account of alleged libel in an article of Nov. 6, 1909; also in previous articles.

“The Journal is a newspaper, and as such its duty is to tell the truth. The industry suffers from the machinations of loose promoters…The Ely Central promotion was a flagrant case, and we told the truth about it. If the truth be libel, let them make the most of it!”

Multifaceted ‘Investments’

Gold may often have been the main focus for scams, but it is by no means the only one. Diamonds also have an irresistible allure for unwary investors.

In his book, Plazak cited the example of the major U.S. diamond scam of 1872, in which the swindlers set up a fake deposit in a remote area of northern Colorado. The timing was right, with the discovery of diamonds in South Africa only a few years before. The ground was salted with diamonds, sapphires and rubies bought overseas, a holding company was established, the mining law was slightly amended (courtesy of one Benjamin Butler—remember him?), and 160 acre lots were offered to potential miners. Noted geologist Clarence King recognized the fraud for what it was, and sounded the alarm.

Diamonds also featured more recently in this context in what the SEC has defined as the largest penny stock fraud in history. In 2014, one of the perpetrators of the CMKM Diamonds scam received a four-year jail sentence, six people initially having been arrested in 2009 over charges relating to conspiracy to sell unregistered securities and other fraudulent activities.

In its initial press release about the case, the FBI alleged that through a recycling process, the swindlers issued 800 billion shares in the shell company, CMKM, over an eight-year period. “Although CMKM shares usually traded at less than a penny per share, the sub-penny price was offset by the astounding volume of shares traded. Indeed, records reflect that during the course of the fraudulent scheme approximately 40,000 investors purchased CMKM stock,” the FBI noted. The scam is believed to have netted the gang some $60 million.

Shortages Drive Metal Bubbles

Two 20th century examples of how market shortages can lead to surging share prices, increased opportunities for scams, and investors getting their fingers burned are provided by the Poseidon nickel bubble of the 1960s, and the boom in U.S. uranium production in the previous decade.

For many of today’s readers, Poseidon may well have been the first time that they became aware of just how volatile the mining finance sector can be. Poseidon NL’s (not to be confused with today’s Poseidon Nickel) discovery in 1969 of nickel mineralization at Mount Windarra in Western Australia came at a time when the nickel market was tight. Nickel was in strong military demand and supplies were threatened by a strike at Canada’s major supplier, Inco. In addition, there had been 10 years of strong growth in the Australian minerals sector, and investor expectations were high.

Speculation, driven in part by somewhat misleading information on grades, not only drove Poseidon’s share price higher, but had a knock-on effect on those of other Australian nickel exploration companies and producers. Between the discovery announcement in September 1969 and the start of 1970, Poseidon’s share price rose from less than A$1 to A$270.

As John Simon of the Reserve Bank of Australia noted in his 2003 paper, Three Australian Asset-price Bubbles, initially the price increases reflected the fact that Poseidon was a small company with a limited number of shares in issue. After that, speculation was the driver. Simon pointed out that “a number of companies floated with ‘empty’ prospectuses containing no details on any prospects. Indeed, insiders managed to extract a lot of money from the boom.”

“There is no clear indication of what triggered the [subsequent] decline but the activities of the fringe companies no doubt helped to tarnish the stock market in many people’s minds,” Simon added. “At its peak Poseidon had a market capitalization of A$700 million, which was about a third of the capitalization of BHP at that time.”

Poseidon did get its mine into production, but it never did much better than break even. Of wider significance was the appointment of the Rae Committee, whose report in 1974 “documented the abuses that had gone on during the Poseidon boom. It highlighted how the stock market had been poorly regulated and that much of the information relied upon by investors was uncorroborated rumor, and recommended a number of changes to financial and stock-market regulation.”

Salting and Seawater

Probably the oldest trick in the swindler’s book, salting has been used widely to enhance the attractiveness of all sorts of minerals. A shotgun cartridge of gold dust fired into a gravel pile or a barren heading can make all the difference.

And as well as the basic techniques such as simply adding an appropriate amount of metal to a sample—either as particles or in solution—other, more sophisticated (and time-consuming) approaches have also been devised. The melted half-dollars at North Ophir is a case in point.

In this context, Plazak mentions an imaginative attempt in 1871 at convincing investors of new tin deposits in Canada. Having found some suitable rock outcrops, the swindlers constructed “tin-bearing” veins using ore imported from Cornwall, before selling the property on the London market for $1 million. Even the British were not averse to scamming their own investors in this way, with one Joseph Aspinall even going to the trouble of cementing ore samples to underground haulage walls in an abandoned Welsh lead and zinc mine. By having a small workforce to fake mining activity, Aspinall reportedly took his investors for £166,000 before the fraud was discovered. His “Klondyke mine” scheme earned him 22 months in prison in 1920, although apparently this did not deter him from further entrepreneurial activity later in the decade.

As for seawater, Plazak’s account of the Reverend Prescott Jernegan’s claims to have a process to recover gold from seawater—something that was not actually achieved until the 1960s—makes interesting reading. In its March 26, 1898, edition, E&MJ was not impressed, however.“ “A mining enterprise ‘run’ by a minister of the gospel, of any sect or church, is a good thing to avoid. We cannot recall a single instance where it was not an outright swindle or a bungling failure,” was the comment.

Utah Uranium: The Penny Stock Bubble

After World War II, the U.S. needed uranium. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was established in 1946, and within a short time had put in motion a program to build a large stockpile. The confirmation of substantial uranium mineralization in eastern Utah in 1952 then paved the way for a boom that lasted for much of the next 10 years, until the AEC realized that it had more uranium than it needed, and pulled the plug on its guaranteed purchasing scheme.

As Raye C. Ringholz described it in From the Ground Up: the History of Mining in Utah, the AEC was the ideal customer. “Besides bonuses of $1,000 for new discoveries of high-grade ore, the only legal customer for the ore paid a guaranteed price of up to $50/ton for 0.3% uranium, threw in six cents per ton haulage allowance, and continued to construct roads, build processing mills, and furnish the services of professional geologists.”

According to Ringholz, promoter Jay Walters Jr. realized that Utah’s very lax securities laws offered a way to float new mining and exploration companies through issuing penny shares. The scheme fueled a boom, with the number of stockbrokers and traders—particularly in Salt Lake City—multiplying rapidly. An article in the Utah Daily Herald from August 1954 described how the back room at a downtown restaurant, the Grabeteria, had been transformed into a brokerage house.

“Hanging on the wall beside the menu is a list of 39 uranium companies offering shares from as little as two cents up to $1.62. Thousands of Salt Lake City residents have dug into their savings to buy stock,” the paper reported. “Most of the companies have never produced any uranium. They own mining claims in various parts of the Colorado Plateau, and it’s yet to be seen whether their parcels of windswept land contain anything but rocks and rattlesnakes.”

E&MJ made no editorial comment as such, but did carry a news item in April 1955. “Senator Chavez (D., N.M.) has proposed an investigation of uranium mining stocks by the Committee on Banking and Currency, Senate Resolution 59, although action on the plan may not begin for another month.

“The Chavez proposal calls for a Securities Exchange Commission minimum of $300,000 as a requirement prior to issuance of uranium stocks. The resolution does not call for hearings, and the investigation will probably be carried on by staff members though analysis of the amount of investor-risk involved in speculative stocks offered for certain uranium ventures.”

With the SEC watching more closely, and the AEC trimming the generosity of its buying commitments in 1958, the uranium boom petered out. So did the penny stocks bubble.

The Salting Spree That Led to NI 43-101

If anything good can be said to have come of the Busang fiasco, it was the major overhaul that subsequently took place in Canada’s reporting requirements, with the introduction of the industry standard NI 43-101. Without question, something similar would have been devised in any case, but Busang provided the catalyst that speeded the process significantly.

Given its relatively recent history, much of what has been written about the Bre-X swindle is freely available in the public domain. By way of an overview, what follows is a precis of events both during and after the scam was unveiled.

Having been established in 1989, Bre-X Minerals began exploring for gold at the Busang property in Kalimantan four years later. Busang had already attracted other companies, but their exploration had proved unsuccessful.

By 1995, Bre-X was reporting significant gold assays from its drilling program, with its consulting company estimating a resource of more than 30 million oz—a figure that rose to more than 70 million oz by early 1997. Comments then made by the company’s chief geologist, John Felderhof, of a 200-million-oz resource were widely reported, with the company’s share price having risen in the mean time from a few cents to more than C$285.

With the Indonesian government looking for a share in the action, a deal was cut that brought in Freeport McMoRan Copper & Gold (FMCG) as the preferred “major” to direct the project going forward. However, its duplicate drilling soon began to show minimal gold values, and a report on third-party analysis by Strathcona Mineral Services, issued in early May 1997, condemned the entire project as fraudulent. With Strathcona stating that the data had been “falsified on a scale without precedent in mining history,” Bre-X’s share price crashed.

Subsequent investigation showed that there had been systematic salting of Bre-X’s drill samples, with the project geologist, Michael de Guzman, identified as being the likely perpetrator. His death (real or faked) immediately before the fraud was unveiled closed that line of inquiry, and while the Ontario Securities Commission had already opened an investigation into insider trading at Bre-X, Felderhof’s acquittal in 2007 on charges relating to this and to issuing misleading press releases brought to an end legal actions against individuals involved. The final suit brought by investors was dismissed in the Ontario courts in April 2014, when it became apparent that further pursuit of claims had no chance of success.

“This was one of the great frauds perpetrated in North America,” said Paul Pape, a Toronto lawyer for investors in the case, in an interview reported in the Globe and Mail at the time. “And nobody was convicted of it, and nobody paid any money.”

While Felderhof, de Guzman and former Bre-X chairman David Walsh made substantial amounts from selling holdings in the company before the crash, the loss to shareholders has been variously reported as being as high as US$3 billion. Major losers included three Canadian provincial bodies, the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement Board, the Québec Public Sector Pension Fund and the Ontario Teachers Pension Plan.

One of the key contributors to the way in which Bre-X was able to continue to promote Busang unchecked was the fact that it had largely been funded through private placements—which at the time had lower regulatory requirements for disclosure than those needed for public equity-funded companies. The subsequent introduction of NI 43-101, whereby mineral resource statements have to be professionally verified, brought in a new level of scrutiny aimed at providing investors with greater protection from unsubstantiated claims.

In its July 1997 edition, E&MJ passed comment on Walsh: “To escape jail, the Bre-X founder must convince the world he is a moron—not a crook.” Walsh died from natural causes the following year.

Shares for the Boys

Butte Mining, floated for £60 million on the London stock exchange in 1987 and delisted just 10 years later, fell apart when it was discovered that some of the leading lights in the company had, in fact, been feathering their own nests. Reporting on the convictions of three of the four defendants in the subsequent court case, Clive Smith, John Clarke and K. Malcolm Clews, the U.K.’s Independent newspaper explained that Smith had been “able to influence Butte decisions—including the sale of assets he owned to the company—after binding his co-defendants with golden handcuffs, the secret ‘gift’ of shares.” Smith also “hid his promotion of the flotation from the Stock Exchange by using a front company.” The report went on, stating that, “a web of offshore trusts and companies ensured the massive shareholdings in Butte owned by Smith, Clarke and Clews were never revealed to investors.”

Allegations made during the trial included the defendants having “exaggerated the value of Butte’s Montana mining rights during two share issues and concealed the fact they had personal interests in the venture,” Accountancy Age reported at the time.

The convictions were just one aspect of the raft of legal disputes that followed the discovery of the fraud, with Butte’s delisting coming after it became apparent that the costs involved in pursuing cases would not be in its shareholders’ interests. The company was finally dissolved in 2010.