At a time when pioneers were beginning to discover the vast natural resources of the American West, publishers launch a weekly journal dedicated to mining

By Steve Fiscor, Editor-in-Chief

Editor’s Note: In 2016, Mining Media celebrates 150 Years of E&MJ, which will culminate with a Special Collector’s Edition (September 2016) to be distributed at MINExpo 2016. As a lead up to this event, E&MJ will provide monthly snapshots of its history.

Serving an industry for 150 years is a milestone only a few companies have achieved. Engineering & Mining Journal (E&MJ) traces its roots back to 1866, when it was originally founded as the American Journal of Mining (AJM). The California gold rush was at its peak and the Comstock Lode had just been discovered outside of Virginia City, Nevada. Copper mines were exploiting native copper deposits in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The lead mines in Missouri were established as were some precious metals mines in the Carolinas.

Headquartered in New York City, the AJM debuted as a weekly tabloid. In 1869, the name would eventually be changed to The Engineering and Mining Journal. The first edition was published on March 31, 1866. The mast read the ‘American Journal of Mining, Milling, Oil-Boring, Geology Mineralogy, Metallurgy,’ etc. The editor was George Francis Dawson. The lead story was a new rock drilling machine and a lithographic engraving provided a sketch of a miner operating the drill underground.

AJM was published with a very consistent fashion. The type was set to a three-column format with a lithograph on the front page. The first few pages provided a collection of news stories and a summary of mining activities by state and country. Most of the news was from the frontier states and territories, with consistent reports from British Columbia, Mexico, and New Grenada (the region now known as Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador and Panama). Occasionally mining engineers would file reports from other parts of the world.

The news section was followed by a page or so of articles written by Dawson expressing opinions on behalf of the AJM. The journal also published the current prices for metals and mining-related stocks, and patent claims related to mining and mineral processing. The last page, which would now be known as classified advertisements, offered everything from six shooters to steam engines.

Although not much is known about Dawson, he penned the following salutatory in the first edition, “Buoyed up by the kind assurances of many influential friends—some of them well known in their several departments of science—I assume editorial control of the Journal of Mining with a determination, so far as lies in my capacity to make it a success. Puffery is my special abhorrence, and so long as I conduct the Journal nothing of the kind shall be seen in its editorial columns. Politics—in the popular acceptance of that term—will be utterly ignored, because incompatible with the spirit and scope of such a paper. Without any further promises, I prefer to let the Journal stand upon its own merits.” Below the salutatory, he apologized for not being able to include as much information as he could due to publishing deadlines and problems with the type setting.

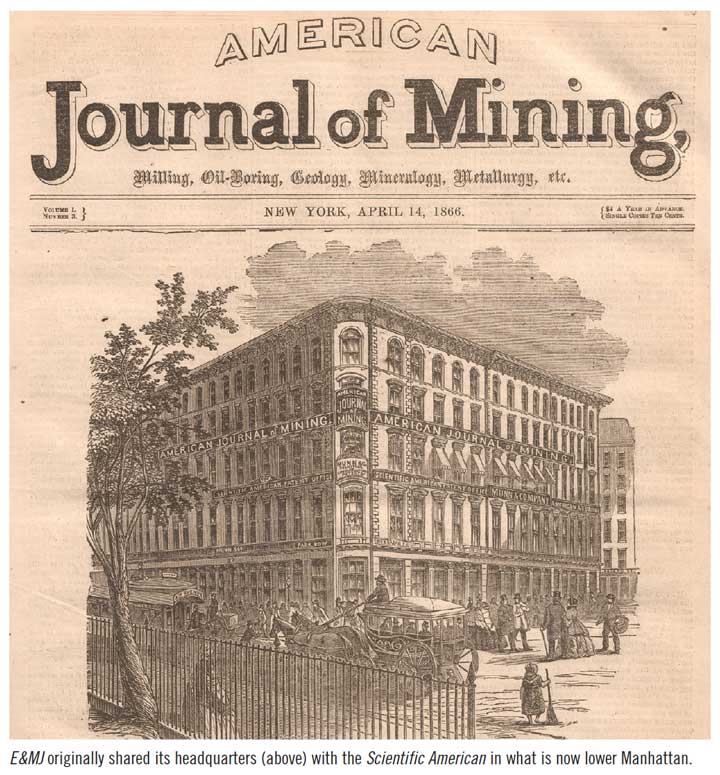

Subscription costs for the AJM were $0.10 per issue or $4 per year ($1 in 1866 would be worth $15 today). The journal was published every Saturday at noon and the masthead gave the address of the publisher (Western & Company): 37 Park Row, New York. Today, that would be near the Brooklyn Bridge in lower Manhattan. They were proud of their new title, its location and its affiliation with Scientific American. The Park Building appears on the cover of the third edition. Soon, Dawson begins to hear platitudes from various contributors and competitors about the scholarly nature of the AJM and he routinely published them.

DEVELOPING THE MINES OF THE NEW FRONTIER

Pioneers were leaving the urban setting in pursuit of the “American dream” only to encounter hardship, lawlessness and hostile natives. People traveled by horseback, carriages and riverboats. “Few have begun to realize the extent of the 12 states and territories on our Western borders, whose vast stores of mineral wealth are yet to attract teeming multitudes to them,” Dawson wrote.

The pioneers that reached the American West found scenic beauty and gainful employment, but the work in the mines was difficult. The miners and mining engineers in those days would have scoffed at today’s notions toward regulations, environmental concerns and aboriginal rights, offering to “fill them with lead rather than give them bread.” It was, after all, survival of the fittest.

The AJM begins to set benchmarks for production and track the number of mining companies and mines. However, census information from 1850 and 1860 is incomplete and it becomes apparent, that although it’s probably the best information at the time, it’s only a loose understanding of what is happening in the field.

The rich gulch and placer mines of California, Colorado, Montana, and Idaho begin to gradually wash out and the attention of both the miners and “capitalists” funding the operations, begins to turn toward quartz deposits, which has been justly termed “the mother of gold.” It’s also one of the hardest geologic formations they have pursued. Dawson offered an editorial explaining that it’s only a matter of time before American ingenuity prevails and quartz mining becomes a profitable business.

The inaugural journal proudly announced that the first American School of Mines has been founded at Columbia College in New York. Until this point, mining engineers were educated in England and Saxony, arguably the birthplace of modern mining.

In the same edition, Dawson announced the American Bureau of Mines. Unscrupulous operators were palming off worthless mining properties on investors, which was tarnishing the image of miners. A number of wealthy citizens formed an association, the American Bureau of Mines, to “bring the miner and the capitalist together upon an honest basis—the one with his valuable mine, the other with his money to develope (sic) it.” In the second edition a Board of Trustees and Experts were named for the American Bureau of Mines. Many of the experts also served as faculty at the Columbia School of Mines. The bureau’s mantra was simple, “Mines, mineral lands, and resources examined and reported upon. Competent engineers furnished to Mining Companies.”

TECHNOLOGY ADVANCES

At the time, the mines were starting to use compressed air to power equipment underground. Each of the early editions of AJM featured a piece of equipment prominently on the front page. The second edition opened with the “Little Giant” quartz mill. Weighing in at 1,100 lb, it promised to have the grindability of a stamp mill, but with a much higher capacity. Readers reported pulverizing 1,000 lb/h producing 5,000 mesh dust. While most of the early editions featured a portable steam engine on the front page, a centrifugal pump appears on the front page of the September 1 edition. Portability in those days meant that the system mounted on a sled could be towed by two draft horses.

The use of nitroglycerine as a blasting agent held great promise, but handling and transporting it had become an issue. Major explosions killed dozens at transfer points in the shipping process. Some states were considering laws to make the use of nitroglycerin illegal. Meanwhile, miners continued to experiment with its use to break rock. After inventing a detonator and designing a blasting cap, Alfred Nobel turned his attention to rendering nitroglycerin innocuous. In 1867, he would invent dynamite. In the meantime, however, the U.S. Senate passed a bill prohibiting the transportation of nitroglycerine on any vessel or carriage carrying passengers. AJM continued to boldly defend its use.

Most of the stories were submitted by miners and mining engineers. The correspondents discussed mining and mineral processing, and they also discussed their travels and the cultures they encounter.

In addition to the mining-related articles, the American Journal of Mining also covered some of the discussions that probably took place around the campfire, such as the shape of the Earth. Some believed it to be lemon-shaped while others thought it would likely resemble an orange. They also debated the usefulness of the Moon and tidal changes.