In the fifth installment of this six-part series, the author explains how identifying and structuring the right type of organization can improve maintenance performance

By Paul Tomlingson

Development of the mining maintenance program acknowledges the unusual, often harsh demands on maintenance personnel in support of mining operations. It requires fortitude to change a shovel cable while snow is arriving horizontally and skill to command several hundred such personnel as their managers must do. Program documentation spells out who does what, how, when and why—serving as a starting point for determining the best organizational configuration.

As these aspects are being considered, the desirable attributes of a future organization must also fit the demanding circumstances of mining. Will the organization, for example, interact cooperatively with other departments? Can it be flexible and responsive and use information effectively? Can our personnel adapt?

EXAMINING THE TYPES

Against such requirements, a range of organizational types should be examined to identify possibilities. Would traditional organizational models work? Could the best features of several models be successfully blended together in a hybrid organization? Could existing staff and personnel fit organizational demands? Various types of organizations will exhibit pros and cons requiring critical examination. For example:

Centrally controlled organization—Centrally controlled maintenance organizations lack flexibility and responsiveness. They are best used in mine-wide support organizations like lubrication or a component-rebuilding shop staffed with personnel possessing unique skills.

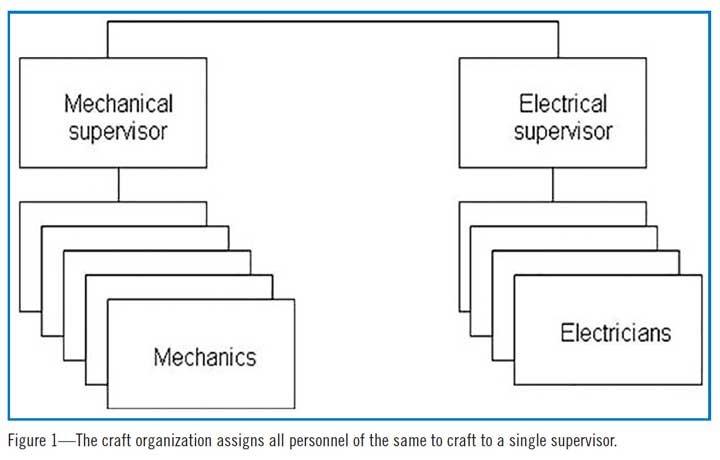

Craft organization—The craft organization assigns personnel of the same craft to a single supervisor. This single-craft orientation means that major jobs requiring many different skills must be drawn from other organizations. Thus, the success of many major multicraft jobs performed by craft organizations will depend on the quality of job coordination. Anytime all personnel are placed within one organization, that organization tends to become the sole decision-maker on how the group will be utilized. Then, when maintenance needs at the plant-level are unknown to the group, the result is often the wrong or least productive use of personnel. Herein is a significant drawback of the craft organization. The most prominent justification for the craft organization is the promotion of the group’s craft skill. This is also a weakness. The boundary lines within which craftsmen apply their skills are invariably too narrow. Then, when compounded by labor contract craft jurisdictions, poor productivity can result.

Consider, for example, the task of replacing a simple electric motor. A millwright could easily do the job but, if the labor contract prohibits him from performing electrical work, an electrician must assist. Thus, a simple one-man, half-hour job costs twice as much and downtime may be doubled if the electrician is not immediately available. The expansion of the jurisdiction of each craft would improve this situation. However, this is not always easy to negotiate. Moreover, while newly negotiated language might broaden craft jurisdictions, it may not change the way individuals do the work. Thus, old habits and poor productivity remain.

Separation of electrical and mechanical skills often plagues the craft organization. The single-craft alignment of personnel in craft organizations also inhibits the expansion of skills that are required to maintain modern equipment. This is best seen in the traditional separation of mechanical and electrical trades in the craft organization. While the skills involved are different, there is no reason for the physical separation of crews. Some organizations justify this separation by claiming that only a mechanical supervisor can supervise mechanics and only an electrical supervisor can supervise electricians. This limited view overlooks the fact that the job of the supervisor is work control, not overseeing work. Supervisors are chosen primarily as effective managers of their crews and not as technicians. In addition, operations personnel often wonder why their inoperative equipment must await the arrival of the electrician hours after the mechanical group proclaimed their part of the job is “finished,” for example. Any organization still committed to this physical separation may detract from overall labor productivity (Figure 1).

Separation of electrical and mechanical skills often plagues the craft organization. The single-craft alignment of personnel in craft organizations also inhibits the expansion of skills that are required to maintain modern equipment. This is best seen in the traditional separation of mechanical and electrical trades in the craft organization. While the skills involved are different, there is no reason for the physical separation of crews. Some organizations justify this separation by claiming that only a mechanical supervisor can supervise mechanics and only an electrical supervisor can supervise electricians. This limited view overlooks the fact that the job of the supervisor is work control, not overseeing work. Supervisors are chosen primarily as effective managers of their crews and not as technicians. In addition, operations personnel often wonder why their inoperative equipment must await the arrival of the electrician hours after the mechanical group proclaimed their part of the job is “finished,” for example. Any organization still committed to this physical separation may detract from overall labor productivity (Figure 1).

Modern mining equipment manufacturers will prescribe a total maintenance requirement for their equipment. If craft personnel perform the prescribed maintenance in the separate, disjointed fashion of craft organizations, they handicap their ability to satisfy the skill needs of the equipment they must maintain. They limit their practical maintenance capabilities by their one-skill orientation. The craft organization is unlikely to be flexible and responsive and while they may control their own resources properly, they may not have direct access to all supporting labor resources. Instead, there is often considerable “horse-trading” among craft supervisors as they haggle over exchanging people to assemble the right skills for a major job. In the meantime, valuable response time is lost adding downtime.

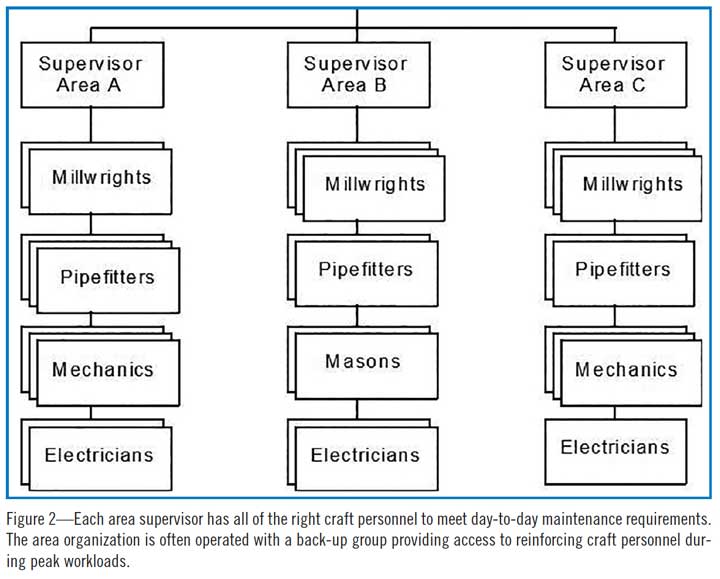

Area organization—An area organization makes one supervisor responsible for all maintenance within a specific geographic plant area like a refinery or smelter. The area organization includes all of the craft personnel necessary to meet day-to-day maintenance needs. Therefore, mechanics, millwrights or electricians could be in the same crew, depending on the workload of a particular plant area. The area organization successfully eliminates the craft jurisdiction problem of the craft organization (Figure 2).

Area organization—An area organization makes one supervisor responsible for all maintenance within a specific geographic plant area like a refinery or smelter. The area organization includes all of the craft personnel necessary to meet day-to-day maintenance needs. Therefore, mechanics, millwrights or electricians could be in the same crew, depending on the workload of a particular plant area. The area organization successfully eliminates the craft jurisdiction problem of the craft organization (Figure 2).

The area organization also suggests that operations would be more satisfied because problems requiring several craft skills are responded to sooner. Therefore, for a plant operation, the characteristics of the area organization are more promising than the craft organization because of their greater flexibility and responsiveness.

Area organizations also have access to other craft personnel required to reinforce them during peak workloads. This suggests that the areas must be supported by other craft groups. Therefore, these groups must have a variety of craft personnel to meet the diverse needs of peak workloads of several areas concurrently.

Consequently, the allocation of labor resources is more likely to meet plant-wide priorities than is the craft organization. Typically, plants wishing to be able to reinforce field areas with additional craft personnel during peak workload periods prefer the area organization. They find that the clear definition of responsibilities is more effective. The most common support organization for the area organization is a pool of backup personnel of all skills needed. Personnel from this pool are awarded to field areas experiencing peak workloads, like a periodic shutdown, based on plant-level work priorities. Pool personnel are returned to the pool after completing work assignments. Depending on plant needs, these personnel are assigned elsewhere to meet labor demands.

In contrasting the craft and area organizations, the best choice in terms of flexibility and responsiveness would be the area organization. However, the quality of planning, the use of technology and quality information are also important considerations.

Team organization—The visualization of smaller, more productive workforces using “teams,” operating without supervision and working efficiently to yield high quality work at lower cost, has great appeal. Organizations visualize better work control through employee empowerment and reduced operating cost with fewer people and potentially greater productivity. However, moving successfully from a traditional maintenance organization to a team organization is a process that must be carefully prepared for and expertly implemented. Thus, forming a team is more than a matter of identifying a group with compatible skills and congenial personalities. It is, more importantly, a matter of making certain the fundamental work control procedures are in place, fully functional and the team members are competent in their use.

Team organizations emerging from a traditional supervisor-crew arrangement often have difficulty coping with “who’s in charge” now that they are without a supervisor. As a result, few traditional maintenance organizations can move directly to a “self-directed” team. Generally, they make this transition by using a rotating coordinator. With a rotating coordinator, one of the team members calls the shots for two to three weeks and then another replaces him. Team members suggest different or better ways of getting the work done. Soon, workable methods emerge for some, but not all, aspects of work control. The ones that work best are retained. Then, another rotating coordinator takes over and tries other methods, focusing on the areas still in need of improvement. Finally, the whole team develops an acceptable way of working together, and they discontinue the rotating coordinator and graduate to a self-directed team.

THE CHALLENGES OF IMPLEMENTATION

Implementing team organizations brings some challenges. Team members must be convinced that the team will help them to operate more effectively, produce better work and realize greater job satisfaction. While productivity, improved performance and cost-reduction are among the team expectations of management, they know the cost of maintenance will not go down unless the number of people doing it and the frequency at which it is done are reduced. Employees are also aware of these facts and opposition to fewer people can result in an adverse reaction to the idea of teams. The maintenance program can provide a framework for team members who as craftsmen had significant experience in diagnosis and repair, but little experience in work control. The maintenance program fills this potential void.

As supervisors are phased out, meaningful tasks must be created to match their considerable talents and experience. Maintenance engineering and reliability tasks are potential solutions. Above all, avoid having former supervisors feel they are redundant as some might try to preserve the status quo or downplay the team effort.

Team formation also means choosing team players carefully to avoid taking on difficult behavioral changes that are required to make the team functional. And, decide whether the new team will be salaried or hourly; salaried employees may be looking for the “perks” (like flexible lunch periods), but maintenance work assignments may not permit them the same latitude afforded salaried personnel.

Establish team decision-making parameters carefully. A team may be qualified to make decisions on how to perform work but not when. Determine in advance the boundaries within which the teams can make decisions.

Determine how craft skills will be evaluated and remedial training provided to improve lagging skills. A team could become a hiding place for a worker who needs skill training. Similarly, others might become “whistle blowers,” anxious to point someone out who doesn’t carry a fair share of the work. These situations can demoralize the teams overall efforts and should be precluded before they can develop.

One newly formed team established a way to find and correct training needs. By linking skills with incremental wage increases, craft personnel were able to request consideration for an increase. A group of the candidate’s peers assembled a group to judge the candidates knowledge. Questioning was tough and fair. If the candidate met the interview requirement, he was then tested for practical experience. For example, a unit of equipment had been rigged with several faults. The candidate was given an opportunity to diagnose and correct all of the faults and restore the equipment to satisfactory condition within a specific period of time. If both the interview and the practical experience requirements were met, the candidate was endorsed for the new skill status and wage increase.

Most team members have not had the training or the experience to develop their own work control procedures. However, a solid program can guide them in developing these skills.

Finally, as the team settles in, verify that a good working relationship with operations exists so that new team members will not have to struggle with “people” problems.

Business-unit organization—Business units, in which one supervisor is responsible for both operations and maintenance, are a very practical and workable organization. Aside from removing the obvious ‘finger pointing’ between operations and maintenance, the business unit builds leadership and professionalism. If, for example, the unit manager is a long-term production type, he can aid the development of greater ‘professionalism’ among craft personnel. They depend on him to lead and he is fully dependent on them for quality work. Thus, the business unit manager who exhibits quality leadership will realize “professional” support from craft personnel in return (Figure 3).

Business-unit organization—Business units, in which one supervisor is responsible for both operations and maintenance, are a very practical and workable organization. Aside from removing the obvious ‘finger pointing’ between operations and maintenance, the business unit builds leadership and professionalism. If, for example, the unit manager is a long-term production type, he can aid the development of greater ‘professionalism’ among craft personnel. They depend on him to lead and he is fully dependent on them for quality work. Thus, the business unit manager who exhibits quality leadership will realize “professional” support from craft personnel in return (Figure 3).

The business unit also brings equipment operators and craft personnel into closer working proximity. There is opportunity for them to create an operations-maintenance team. Soon, the capabilities of operators to perform specific, helpful maintenance tasks become apparent. Similarly, equipment operators learn more about the way their equipment works and are better able to identify potential problems. As the operations-maintenance “team” effort grows, the equipment operators see maintenance personnel in a different light. They are more confident and report problems promptly and correctly. Maintenance personnel, in turn, volunteer shortcuts in adjusting or calibrating equipment. A real team environment emerges. Business units are a potentially valuable method of improving maintenance productivity. Many of these same benefits can apply to the team organization as well.

PAY ATTENTION TO CRITICAL ELEMENTS

Critical parts of organizations must be carefully examined. Some, like planning, have existed for a long time and are still misunderstood. Others are new as with maintenance and reliability engineering and present challenges in their use and placement in the organization.

Planning—The significant benefits of planning and scheduling warrant the correct use of maintenance planners. Their principal task is to organize selected major jobs in advance. Selection of these jobs should adhere to criteria. Resulting work can then be carried productively, with minimum manpower in the least elapsed downtime. This productivity assures quality work to yield longer periods before work has to be repeated, thus slowing the rate of material and spare parts consumption. The benefits are real but often the incorrect use of planners as “parts chaser” or “work order administrators”can limit planning effectiveness. Ensure that program documentation establishes their duties and responsibilities, correct utilization and verification of compliance.

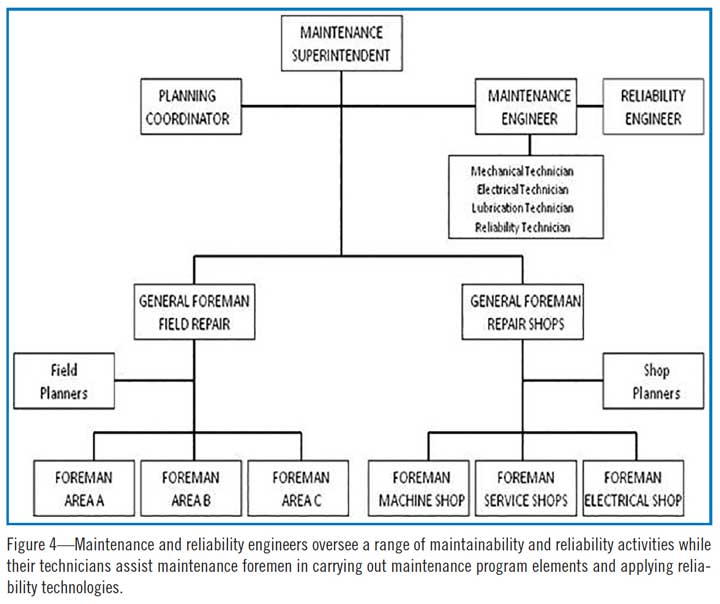

Maintainability and reliability—Ensuring equipment maintainability and reliability are vital objectives for mining operations. Yet, they have also been elusive for the lack of an organizational structure and a cohesive strategy to achieve them. A maintenance engineer provides the tactics that ensure equipment maintainability while the reliability engineer focuses on equipment defect elimination. They function in unison to support the efforts of field supervisors. The maintenance engineer, for example, assures that the ‘detection orientation‘ of the PM program finds problems far enough in advance of failure to allow most maintenance to be planned. The reliability engineer analyzes failures to determine why they occurred and develop solutions to reduce or eliminate them. The results of his efforts are combined with those of the maintenance engineer to enhance the overall maintenance effectiveness. Special attention should be given to including maintenance and reliability engineering in mining organizations (Figure 4).

Maintainability and reliability—Ensuring equipment maintainability and reliability are vital objectives for mining operations. Yet, they have also been elusive for the lack of an organizational structure and a cohesive strategy to achieve them. A maintenance engineer provides the tactics that ensure equipment maintainability while the reliability engineer focuses on equipment defect elimination. They function in unison to support the efforts of field supervisors. The maintenance engineer, for example, assures that the ‘detection orientation‘ of the PM program finds problems far enough in advance of failure to allow most maintenance to be planned. The reliability engineer analyzes failures to determine why they occurred and develop solutions to reduce or eliminate them. The results of his efforts are combined with those of the maintenance engineer to enhance the overall maintenance effectiveness. Special attention should be given to including maintenance and reliability engineering in mining organizations (Figure 4).

Organizational change—The biggest single problem in implementing a new organization or making any organizational change is dealing with resistance to change. Personnel affected must be convinced that the changes are beneficial, first to them as individuals, then to their immediate work groups (crews) and finally to the total operation. They are often aware of pending changes, even if not officially informed. Many may suspect an unfavorable outcome and resist. However, if they are informed of the nature of the changes, they will be supportive. Potential resistance can become support for a potentially beneficial change because they know more about it. Resistance to change is always in proportion to the degree of knowledge about the changes. Therefore, the sooner the education process begins, the greater are the chances of overcoming resistance and getting on with beneficial changes.

Let people know what the changes are and how they will be affected. The more personnel know about the changes being considered, the more that they will think about them in terms of their own situations. With an opportunity to think through the changes and offer alternate proposals, the positive aspects of the change will influence those who are uncertain or opposed. Allow adequate time for a trial period to prove changes are positive and demonstrate that economic security remains intact. Their income, job security and future promotions must not be endangered.

MEASURING THE WORKLOAD

How many personnel, what crafts? This determination seems like a straightforward proposition, but methods for determining it have never been satisfactorily resolved. Ambivalence toward workload measurement must be converted into a logical method.

Establish a policy requiring that the workload be measured. Don’t expect any maintenance department to do it voluntarily. Carefully identify and define the work required of maintenance and acknowledge the implications of how the work is controlled and performed. Measure the manpower required to perform each category of work, PM versus planned work, for example. Assemble a preliminary manpower distribution: What percent of our manpower will be necessary, for example, to perform all PM services or limit emergency work to 10% of manpower?

Tie these considerations to labor utilization reports and watch labor control performance trends. Establish productivity measurements to determine progress while checking backlog levels and PM schedule compliance. Labor utilization reports will confirm whether target percentages are being met.

Mining operations require equipment with much greater productive capacity and improved reliability. But, it will also be much more complex to maintain. Maintenance must also provide the means of applying the newest technology and quality information along with modern management techniques.

But, who will ensure that the personnel who do the actual work are used productively? Regrettably, maintenance departments that check productivity regularly are rare. Yet, productivity measurements remain the most effective way of verifying the quality of labor control. Regular productivity measurements, identification and correction of delays and active steps to constantly improve productivity are part of successful maintenance.

Should mines adopt team or business unit organizations, work control will be accomplished largely by craftsmen team members. With this new responsibility, the task of improving productivity passes to these newly empowered personnel. They must recognize the need and be guided in accomplishing it.

In summary, a variety of possible maintenance organizations are available to mining operations. While selection is guided by program definition and information needs, the care and consideration in developing these elements impacts selection. What key personnel do, along with how, when and why they do it, are aided by effective information utilization. But, the right organization, properly implemented, brings the program to life. Only then can the continuing evaluation process verify the compatibility, progress and achievement required to ensure effective mining maintenance.

Next month: Step 6—The author summarizes the evaluation process and explains and illustrates useful evaluation techniques.

Paul D. Tomlingson (pdtmtc@msn.com) is a Denver-based maintenance management consultant. These articles are based on his book: Maintenance in Transition-The Journey to World-class Maintenance. Readers can obtain information on the book from the author and may request an electronic copy of any one chapter or appendix as a professional courtesy.